|

THE COSTER-FROMANTEEL CONTRACT

John C. Taylor

John Fromanteel's

BRASS AND STEEL

Type

Ctrl+F

to find any text on this page

It has been widely accepted that,

after Huygens adapted a table clock to be controlled by a pendulum and

transferred his patent rights to his design to Salomon Coster, Ahasuerus

Fromanteel in London heard of these new pendulum clock developments and

arranged to send his son, John, who had just finished his

apprenticeship, to The Hague to learn this new construction at

firsthand. A contract was drawn up in The Hague to set the terms of

John’s wages and this technology transfer from Holland to England.

In this article I set out to show that the actual wording within the

contract itself does not support the above synopsis. Rather I submit

that the contract was drawn up under the premise that John travelled to

Holland ready to start work, knowing the layout of the clock trains he

contracted to make. I submit that John brought to Coster’s workshop all

his own brass castings and the necessary steel with him to work for nine

months. The contract was necessary to ensure that John was paid not only

for his labour and his brass and steel but also high enough fees to

cover the design and development costs of the clock in London. It also

ensured that Salomon was forced to purchase all John’s production of

clocks from these kits of parts he brought with him. If John used up his

own brass and steel, only then would Salomon supply him with further raw

materials and John’s fee would be reduced.

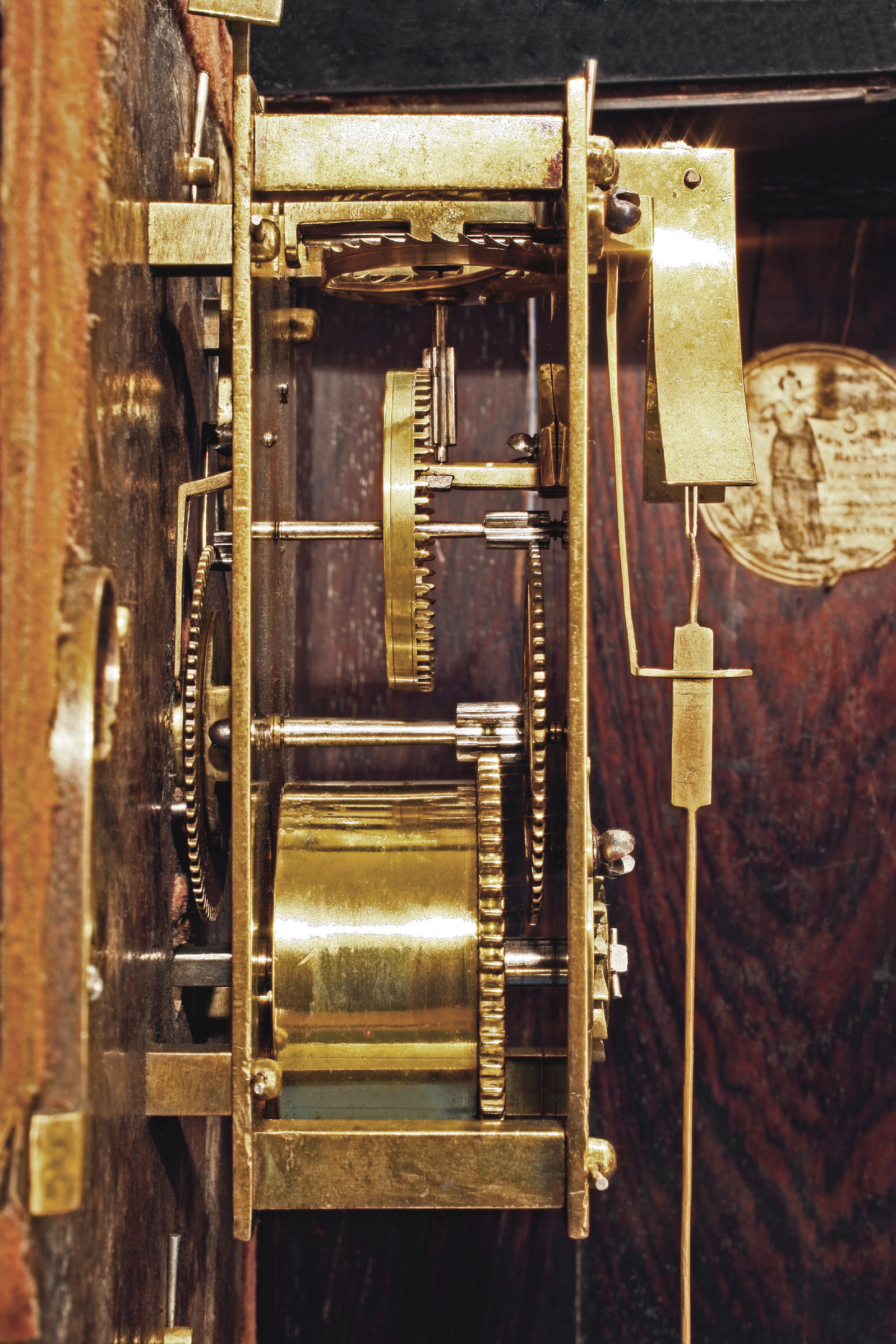

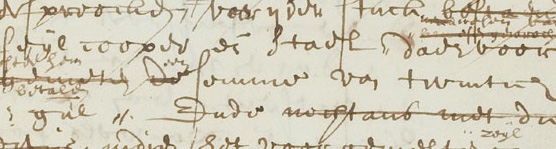

There are five extant early domestic pendulum timepieces

signed by Salomon Coster; Dr Reinier Plomp points out their

similarity and agrees with L.H.J. van Lieshout’s suggestion

that all these movements were made under contract by John

Fromanteel for Coster

(1. They all have

similar sized plates, square pillars

(2 and a delicate,

pleasing train of brass wheels driving steel

(3 pinions.

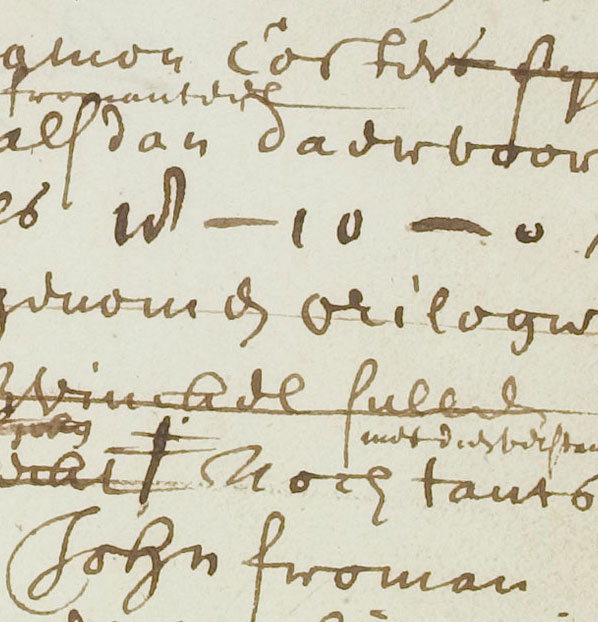

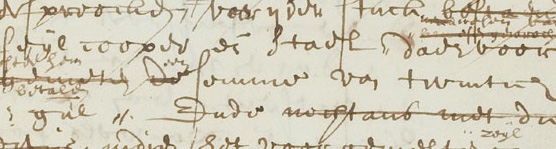

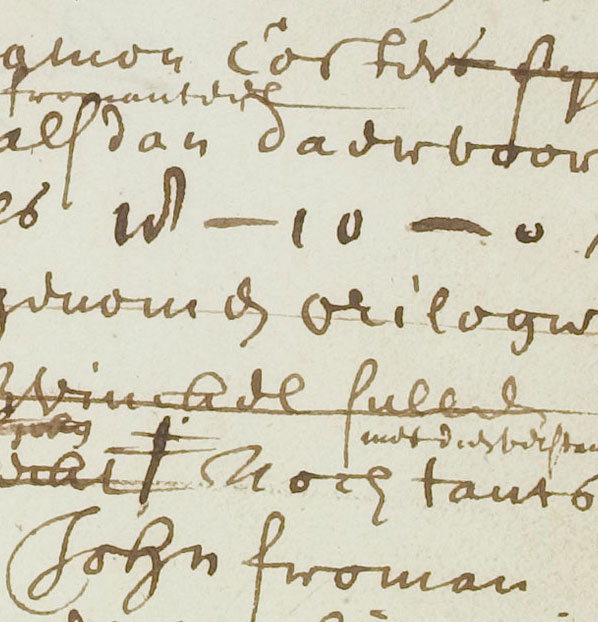

The contract between John Fromanteel

and Salomon Coster has been subjected to much detailed analysis over the

years. One aspect of the contract that appears to have excited little

scrutiny by any reviewer, is the monetary consideration to be paid by

Salomon to John for the clock movements that he produced. In the

translation by Frits van Kersen the signed contract reads:

... for each piece [clock movement]

being of brass and steel, therefore he Coster will pay him a sum of

twenty car. guild.

This clause assumes that John will

most likely supply his own brass and steel and receive twenty guilders.

This conclusion is further strengthened by the exception that now

follows:

And if the aforementioned brass and

steel will be delivered by aforementioned Salomon Coster himself, [ie if

all the brass and steel are supplied by Coster] then he Fromanteel

therefore will enjoy no more as 18-10-0,(4

Coster clocks

Price list in

guilders, Jan. 1659

|

|

Weight |

Spring |

Striking |

30 hr. |

8 day |

Price |

|

● |

|

|

● |

|

48 |

|

● |

|

|

|

● |

60 |

|

● |

|

● |

● |

|

80 |

| |

● |

|

● |

|

80 |

| |

● |

● |

● |

|

120 |

|

● |

|

● |

|

● |

130 |

|

● |

|

|

● |

130 |

In a letter by Huygens to Boulliau dated 16 January 1659

we find a specification of the various clocks deliverable by

Coster, including prices.

Dr Reinier Plomp gives ‘the price of

a complete Coster timepiece going 30 hours, listed by Huygens as D.fl 80

...’.(5 This is the retail price; Huygens’ letters do not contain

information on Coster’s ex-works price.(6

This is not the place to discuss Business School type market theories

such as ‘Demand for a product increases at least tenfold if the price is

halved’, but this retail price of eighty guilders, set for the world’s

first accurate to a minute domestic pendulum timepiece, has to achieve

two interlinked but different competing objectives:

1. The price has to be low enough to

entice buyers. If the price is set too high there may be no buyers to

come forward to purchase these new but unproven clocks. People in

general do not like to be the first to buy an innovative but untried

product.

2. The price has to be high enough to

restrict sales. If the price is set too low, Huygens would have been

overwhelmed with orders that Salomon would be unable to fulfil. If goods

are not delivered promptly customers quickly become disillusioned and

cancel their orders; they fear the possibility of a swindle: the product

is then condemned by word of mouth making further sales virtually

impossible. An insatiable demand from too low a price would result in a

huge loss of face for Huygens. A further Business School theory is: ‘It

is always possible to reduce price but it is difficult or impossible to

increase it without killing all the product’s pent up demand.’ It would

appear that Huygens did set his retail price high enough to ensure he

was not overwhelmed with orders that Salomon was unable to fulfil; thus

his eighty golden guilders was therefore a high price.

The modern perceived

wisdom of the seventeenth century is that labour was cheap and materials

were expensive. However, John’s labour costing 18½ guilders and the

materials in the movement costing only 1½ guilders, appears to turn

this generalisation on its head to expensive labour(7 and cheap

materials.

After paying John his direct cost for

his materials and labour, Salomon’s ex-works price still had also to

cover the costs of the dial, velvet, silver or silvered chapter ring and

lambrequin, hour and minute hands, wooden case with its door, glass and

lock with the key, two pairs of hinges and hanging eyes and all the

materials and labour. More direct costs were involved in final assembly,

setting up the pendulum, bringing to time and testing. Each clock then

had to be partly disassembled, carefully packed most probably into a

custom-made transit wooden box before the whole was wrapped in

protective padding such as being sown into a hessian sack; then there

are all the costs of delivery. In addition, Salomon’s overheads included

his own wages, rent and taxes on his workshop, repairs and maintenance,

heating, lighting, legal fees, interest and finance costs, postage and a

host of other small business costs.

Huygens then had to unpack and check

the clocks for delivery damage, repack, deliver and set up the clock for

his customer as well as finance the whole transaction. He had his patent

fees, travel costs and advertising correspondence. He had Horologium for

the scientific kudos and, although his correspondence may remain silent,

I find it difficult to believe that he went to the trouble and expense

of patent applications together with the delivery costs if this

broughthim no personal pecuniary advantage.

Thus John’s labour appears a very

high percentage of the final retail price in comparison with Salomon and

Christiaan’s large additional costs and overheads.

In the translation ‘And yet with that

condition: if the aforementioned brass and steel…’ the original Dutch

‘indien’ may be more literally translated into ‘in case’ further

changing the emphasis slightly ‘And yet with that condition: in case the

aforementioned brass and steel...’. The contract uses ‘if ’ or ‘in case’

to imply an unlikely event rather than stating ‘when’ to imply a likely

event that Salomon has to supply (all) the brass and steel to John

whereby John receives only 18½ car.

gld.

Fig. 1

Side view of a John

Fromanteel movement in a Coster timepiece dated 1658, showing the

movement. Note the square pillars, typical for Fromanteel’s early style.

Thus it is logical to assume John was to start off supplying all his own

brass and steel and Salomon would take over the supply if and only if

John had used up all his own brass and steel.

We can draw four

conclusions from this clause on the fee in the contract:

1.

It assumes that John will most likely supply all his own brass and steel

and receive twenty guilders for a completed movement.

2. This

is an all or nothing requirement, no consideration is postulated in the

agreement if John has to obtain even one small piece of brass or steel

from Salomon. Thus neither of the signatories to the contract considered

this a likelihood.

3.

In the unlikely event that Salomon has to supply John with all the

necessary brass and steel for a complete movement, John will only

receive 18½ guilders.

4.

John’s labour was particularly costly at 23 per cent of the 80 guilders

retail selling price of the finished clock.

The above conclusions

raise further questions that are the crux of this article:

1.

Why should John’s labour appear so expensive?

2. How

did John Fromanteel know what brass and steel were necessary for the

clock movements he was contracting to make?

3. From

where did he obtain his brass and steel that the contract assumes that

he will use? There is no mention in the contract of wood for the clock

cases, velvet dial covering, nor of silvered parts and engraving and it

is generally accepted that ‘each piece’ in the contract refers solely to

the clock movements. Salomon was to supply the rest of the visual

components, dial, etc. and the complete case.

Some of the Coster signed

clocks have brass dial plates and some have steel dial

plates.(8

The five extant movements

supplied by John under the contract are all very similar with matching

sets of brass component listed in Table 1.

All twenty-nine brass

parts were made from twenty-five different types of castings, each

requiring their own patterns.(9

The raw castings had to be hammered to toughen up the soft brass and

then worked and filed up into precision parts for the clock. For

example, the flat spring barrel casting would be hammered round, the

ends brazed together and then turned on a pole lathe to perfect size.

Wheel cutting engines, I understand, were not yet perfected and wheels

and pinions were marked out and sawn and filed to shape. This was the

work that John was undertaking together with forging, turning and filing

the main steel parts. These would most likely have been made from steel

bar or rod and have been as listed in Table 2.

End

of this section, click

here to continue.

NOTES NOTES

|

|

|

|

1 |

Reinier Plomp, ‘The Prototypes of ‘Hague Clocks and ‘Pendules

Religieuses’ ’, Antiquarian Horology 30/2 (June 2007), 196-208,

esp. pages 198-9 (listing the five known timepieces), 201 and

Conclusion 2 on p. 208. |

|

2 |

Square pillars are a feature of the earliest extant English

pendulum clocks signed by Ahasuerus Fromanteel, see exhibits 7

and 8 in the catalogue of the 2003 AHS exhibition Horological

Masterworks. |

|

3 |

I make no differentiation between ‘steel’ as quoted in the

translation of the contract and ‘iron’ as often referred to by

Dr Plomp in his articles, as I feel both words are intended to

describe the ferrous material in common use at the time. I

simply use ‘steel’ throughout for consistency. |

|

4 |

Frits van Kersen, ‘The Coster-Fromanteel Contract Re-examined’,

Antiquarian Horology 28/5 (March 2005), 561-67. I am grateful

for Frits van Kersen for helping with the nuances of the Dutch

language together with the chronology and help in correcting my

dyslexic orthography. All mistakes remaining are entirely my

own. |

|

5 |

Plomp, ‘The Prototypes’, p. 201. D.fl = Dutch florin is

interchangeable with a Carolus guilder. |

|

6 |

H.M. Vehmeyer, Clocks, Their Origin and Development

1320-1880 (2005), p. 227: ‘Coster’s function seems to have been

limited to the contacts with Huygens and the actual production’. |

|

7 |

Vehmeyer, Clocks, p. 225: ‘the average worker earned at best 40

guilders in a whole year’. |

|

8 |

Plomp, ‘The Prototypes’, p. 200. |

|

9 |

At the AHS reception on 26 February 2008 at the Oxford Museum

for the History of Science for the display of the newly restored

Ahasuerus Fromanteel roller cage longcase of c. 1661, the

restorer Matthew Read made the point that all the brass wheels

were cast with the crossings in place. Under close examination

he could still observe the finishing to clean up the casting

surfaces on the crossings. |

|

10 |

G.F.C. Gordon, Clockmaking Past and Present (1946), Materials p.

5, Motive Power p. 65. See also Vehmeyer, Clocks,

p. 225:

‘Generally speaking, the latter type [spring driven] are more

expensive’ [than weight driven]. |

|

11 |

Percy G. Dawson, C.B. Drover and D.W. Parkes, Early English

Clocks (Antique Collectors’ Club, 1999), p. 7. |

|

12 |

J.H. Leopold, ‘Some more thoughts on the Coster-Fromanteel

Contract’, Antiquarian Horology 28/5 (March 2005), 568-70 (p.

568). |

|

13 |

Van Kersen, ‘The Coster-Fromanteel Contract Re-examined’, p.

563. |

|

14 |

Rebecca Pohancenik, ‘The Intelligencer and the Instrument Maker:

Early Communications in the Development of the Pendulum Clock’,

Antiquarian Horology 31/6 (December 2009), 747-56; esp. pages

747 and 752. |

|

15 |

Huygens’ Legacy: The Golden Age of the Pendulum Clock at

the Royal Palace Het Loo, 2004, exhibits 5 and 6 in the

catalogue. |

|

16 |

I am indebted to Michael Hurst for this information. |

|

17 |

Plomp, ‘The Prototypes’, p. 208. |

|

18 |

Plomp, ‘The Prototypes’, p. 196. |

|

19 |

Huygens’ Legacy, exhibit 8 |

|

20 |

E.L. Edwards and R.D. Dobson, ‘The Fromanteels and the Pendulum

Clock’, Antiquarian Horology 14/3 (September 1983), 250-165 (p.

253). |

|

|

|

|

Table of contents:

This

article was first published in the Sept. 2010

issue of Antiquarian

Horology.

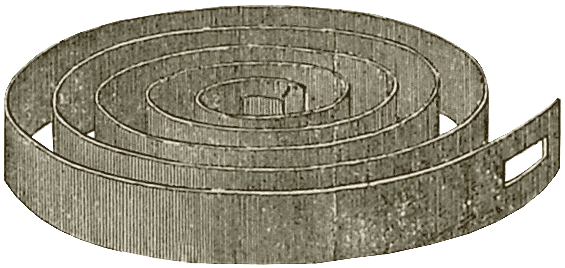

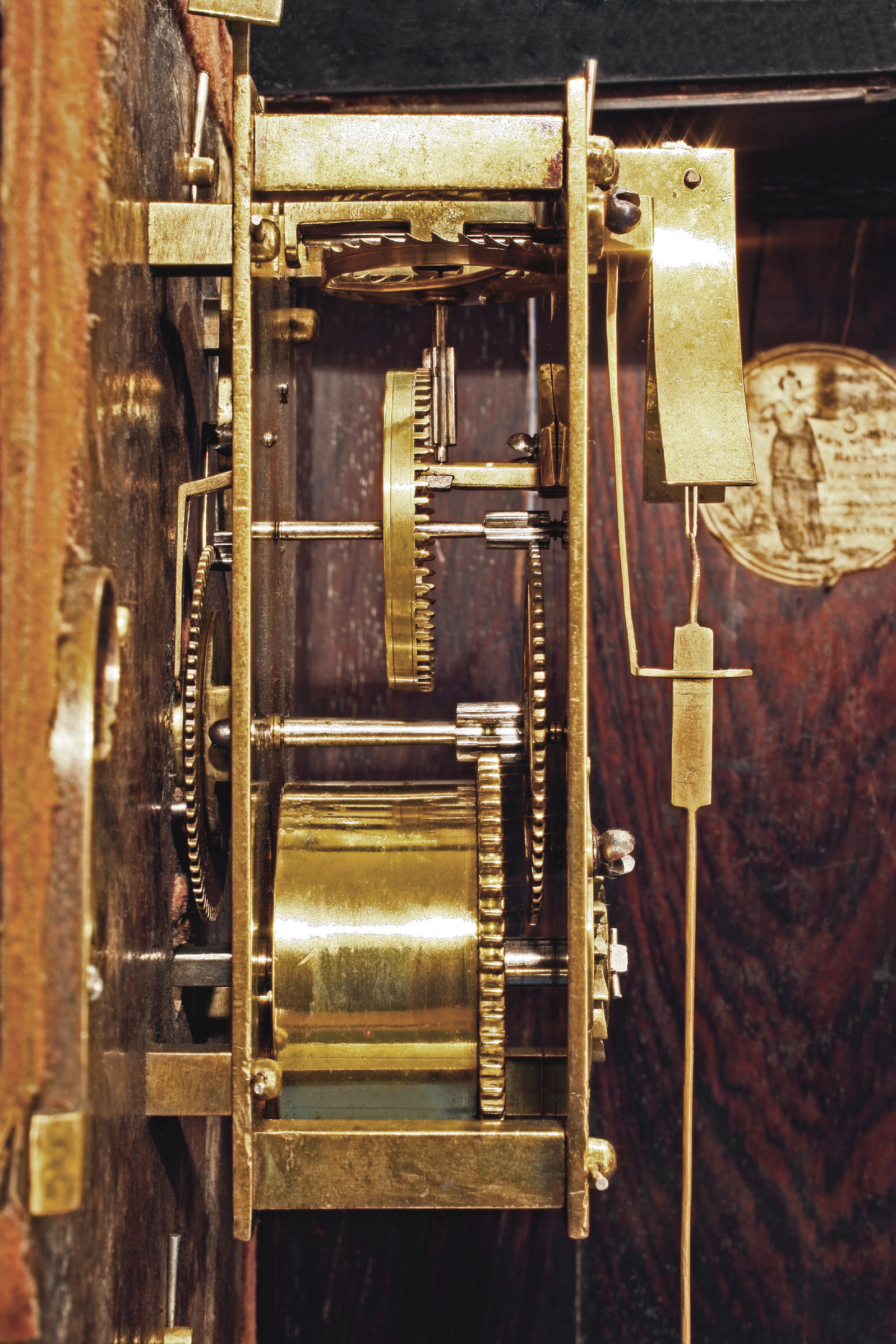

Technically the most difficult

steel part is the clock main spring. Each clock design

requires a unique motive driving energy store, matched to

the duration, the particular train and the chosen pendulum.

The spring in the Coster timepieces is particularly

difficult as no fusee is used to even out the decay in the

spring action as it unwound.

G.F.C. Gordon writes at length

on the problems that the early metal workers had in making

thin steel springs and how only the most costly movements

were spring driven. G.F.C. Gordon writes at length

on the problems that the early metal workers had in making

thin steel springs and how only the most costly movements

were spring driven.

He writes ‘…for one satisfactory bracket

clock spring which was made and used, ten or even fifty were

tried and rejected.’(10 This large, easily seen, spring

driven domestic timepiece, accurate to show meaningful

minutes for the first time ever, was the pinnacle of

scientific achievement and technological manufacturing: in

modern terms, high technology, coveted consumer designer

product; the expensive ‘must have boys toy’ from the middle

of the seventeenth century. Huygens reports in his diary

that he had the pleasure of adapting his first model

pendulum clock on Christmas Day 1656 and by June 1657 a

patent had been granted to Salomon Coster.(11

|

TABLE

1 |

Casting patterns |

Brass parts |

|

|

Front plate and back plate |

1 |

1 |

|

Square movement pillars |

1 |

4 |

|

Great wheel, spring barrel and barrel cap |

3 |

3 |

|

Click wheel and click spring |

2 |

2 |

|

First wheel |

1 |

1 |

|

Contrate wheel |

1 |

1 |

|

Escape wheel |

1 |

1 |

|

Cannon wheel |

1 |

1 |

| Minute wheel |

1 |

1 |

|

Hour wheel and integral pipe |

2 |

2 |

|

Crutch and crutch block |

2 |

2 |

|

Pendulum bob and rating nut |

2 |

2 |

|

Top pottence and bottom potence |

2 |

2 |

|

Backcock, left and right cheeks |

3 |

3 |

|

Motion work bridge |

1 |

1 |

|

Clock winding key |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Totals |

25 |

29 |

|

TABLE 2 |

Steel parts |

|

|

First arbor and pinion |

1 |

|

Contrate arbor and pinion |

1 |

|

Escape wheel arbor and pinion |

1 |

|

Minute wheel pinion |

1 |

|

Verge arbor and pallets |

1 |

|

Hook for main spring in brass barrel |

1 |

|

Winding click |

1 |

|

Crown wheel lower bearing |

1 |

| Tapered

pendulum rod |

1 |

|

Miscellaneous screws |

8 |

|

Miscellaneous taper pins |

4 |

|

Clock spring - the most expensive component in the clock |

1 |

|

|

Totals |

23 |

Therefore one

might probably assume that casting patterns and raw castings

from a Dutch brass foundry must have been available in Coster’s workshop when John Fromanteel arrived in

The Hague in late summer 1657.

For any subcontractor, it

is financially disadvantageous to supply your own materials.

Apart from your own personal cash tied up in the stock, you

personally stand the loss if parts are lost or damaged or

the dimensions are changed and the components are scrapped.

Any faults or mistakes needing replacement are your

own

materials and your personal costs. Thus it is normal

practice and to the advantage of subcontract craftsmen to

solely sell their labour leaving their employer to supply

all the materials on which they perform their work.

If

John supplied his own brass and steel, any faulty finishing

work requiring a new raw piece was his own personal

financial loss: it was not in John’s interest to supply his

own materials, particularly if there was any

development still taking place that might make any parts

obsolete. It was to John’s benefit to have Salomon supply

all the brass and steel for him to work up and finish to a

going clock movement. Yet the contract specifically implies

that the most likely scenario is that John, a 19 year old

newly arrived in a foreign land, will take the

responsibility to supply all his own brass and steel! How

and why would he do this?

Even with John’s likely command

of the language,(12 if, as suggested,(13 he had worked for a

week or two in Salomon’s workshop, using Salomon’s brass and

steel:

1. It seems inconceivable that John decided that

Salomon’s brass and steel were of inadequate quality, or of

such a high price from the Dutch suppliers that he could

make a profit from supplying his own parts.

2. It appears

unlikely that he could visit Salomon’s local Dutch suppliers

and negotiate a better price than Salomon to make it worth

his while financially to take on the responsibility of

supplying all his own brass and steel.

3. If the castings

were not yet available, it would be unlikely for John as a

young itinerant craftsman to have the cash with him to pay

for the patterns to be produced and finance the necessary

batches of brass castings and necessary steel, particularly

as he only was paid for the materials he used after he had

completed each movement.

4. Equally implausible is the

thought that he had to draw up each and every part and

either send the drawings or took the drawings or a set of

parts back to London to enable a quotation to be prepared

and then sets of parts produced and shipped over prior to

the contract being signed.

5. Nevertheless, he went with

Salomon before a Notary and signed a contract thereby taking

the full responsibility to normally supply all his own brass

and steel.

Rebecca Pohancenik has recently established that Ahasuerus

Fromanteel had indeed manufactured and sold pendulum clocks

prior to John Fromanteel’s sojourn with Salomon Coster. She

also links Christiaan Huygens with Ahasuerus Fromanteel,

giving further insight into the origin of possible technical

collaboration.(14

The

little table clocks by Coster exhibited at Het Loo(15

have beautifully shaped pillars. Square pillars were not a

natural progression for Coster. With no power lathes

available to turn up round and complex shaped pillars, such

attractive shapes took much care and effort to produce on a

bow lathe. All the extant very early pendulum clocks signed

by Ahasuerus Fromanteel have square pillars. These appear to

be unique to Ahasuerus’ signed early pendulum clocks. Square

brass pillars can be produced from a raw casting, not just

by filing but by hammering the brass to a tough regular

shape,(16 leaving just the

two ends to be turned round on a lathe. Moreover, Ahasuerus

was an experienced blacksmith and used to hammering metal

into shape. Coster was under pressure to produce sufficient

clocks to meet Huygens’ demand and accepted the Fromanteel

quicker if less visually attractive option.

It is not necessary for me to postulate

that the springs, brass castings, etc were actually made in

the Fromanteel workshop; they may have been made by

specialists nearby in London; I solely suggest that John

must have brought these components with him to The Hague if

he was to sign a contract to supply them.

I conclude that

John Fromanteel arrived at Salomon Coster’s workshop and

signed the contract knowing what brass and steel was

required and brought with him several complete sets of brass

castings, together with the necessary steel rod and bar, as

well as the necessary clock springs. Only if all these

conditions were met would the contract have been drawn up as

it was.

It was John who needed a contract and had it

altered to ensure he had:

1. A fixed price for the work

and materials he supplied.

2. A guaranteed market for the

movements he produced.

3. A high price to cover any

development work that had already taken place in London and

perfections still to take place in The Hague.

Almost the

last clause in the contract gives

John this necessary

assurance:

... provided

the works by which he Fromanteel on the conditions aforementioned will

have been made, he Coster for the stipulated price will be allowed and

obliged to keep.

In other words if John makes the

movements, he is going to sell them to Salomon and Salomon

is required to pay 20 guilders for them.

Plomp in his

conclusion no. 2 says:

The movements of the five

Coster timepieces are so similar that it is justified to

conclude that they represent the movements referred to in

the contract between Salomon Coster and John Fromanteel.(17

To this I would add: ‘and made from a kit of brass

and steel parts and the main springs brought with him from

London’.

We may now conclude that there were at the very least

letters, drawings and specifications of the movements passed

between Coster and the Fromanteels before John’s visit in

September 1657. Most likely one or more sample movements

were produced in London before the approval for the

production of the unique brass castings and mainsprings for

John to take with him to The Hague.

This also opens for

further discussion the clauses in the contract and a literal

interpretation of the following two phrases:

1. ‘John Fromanteel obliges and

commits himself to execute and perfect his watchwork

…’

as an indication that the Coster/Fromanteel design was still

not finalised and some perfection of the mechanism was still

to be undertaken by John. The earliest signed Coster

pendulum clock dated 1657 was found in 1922 by Drummond

Robertson in the Rijksmuseum (as he reports: subsequently

lost) together with the present earliest extant clock also

dated 1657.(18 Whilst the trains were very similar the first

clock solely had an hour hand whereas the later clock also

has a minute hand.(19 Was this the perfection to be carried

out by John?

2.‘…like

he Fromanteel already has made some’ was as a further

substantiation that John had already been producing

prototype Coster pendulum clocks in London. This phrase in

the contract was considered by either Salomon or John or

both as an important additional clause added into the

contract as it is inserted, crossed out and inserted again

in a different place to strengthen the point.

E.L.

Edwards and R.D. Dobson note that the backplate of the

earlier Rijksmuseum clock was signed ‘Samuel Coster Haghe

met privilege’ and point out that signing on the backplate

is an English, not a Dutch tradition. As Salomon corrects a

similar mistake over his name in a contemporary document,

they surmise that this clock must have been made by John

without Salomon’s input,(20 to which I would add: ‘in London

prior to his visit to The Hague’.

I conclude that the Fromanteel family expertise

facilitated in preparing the Fromanteel/Coster design in

London so that the necessary kits of brass castings and

steel together with the mainsprings could be produced for

John to take to The Hague with him, ready to start work. But

it was necessity for John to have a contract to ensure he

was paid a suitable high fee as this was also to cover the

Fromanteel development work in London and not just his own

labour costs. This can all be deduced from the contract.

About the author

Dr John C. Taylor is an inventor with about two hundred

British patents in his name. The company he founded in 1981 won

four Queen’s Awards and last year celebrated selling one billion

kettle controls. His interest in horology started through

navigation – trying to fly a small aircraft from Manchester to

Tokyo. His latest invention is the Corpus Chronophage.

(john@fromanteel.com) Dr John C. Taylor is an inventor with about two hundred

British patents in his name. The company he founded in 1981 won

four Queen’s Awards and last year celebrated selling one billion

kettle controls. His interest in horology started through

navigation – trying to fly a small aircraft from Manchester to

Tokyo. His latest invention is the Corpus Chronophage.

(john@fromanteel.com)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Horological Foundation is endebted to the Antiquarian Horological

Society for making their PDF version of the original printed article

available.

Photo 1: Courtesy of Dr. John C. Taylor, Isle of Man

May

2019, Copyright: John C. Taylor

LINKS

LINKS

Chr.

Huygens' Œuvres Complètes.

(pdf)

Chr.

Huygens Horologium 1658.

(pdf)

The Coster Fromanteel Contract. The Van der

Horst transcription working sheet. (also

PDF)

(This article is subject to ongoing

revisions.)

|

G.F.C. Gordon writes at length

on the problems that the early metal workers had in making

thin steel springs and how only the most costly movements

were spring driven.

G.F.C. Gordon writes at length

on the problems that the early metal workers had in making

thin steel springs and how only the most costly movements

were spring driven.