|

The production and development of the first pendulum clocks in the period 1657 – September 1658

Salomon

Coster

(Type Ctrl+F to find any text on this page)

Ever since in 1888 the first

volume of Oeuvres Complètes was published, much has been written about

Christiaan Huygens’s invention on Christmas Day 25 December 1656 of the

application of a pendulum to a clock movement and the further developments of

the early pendulum clock.

In recent decades, several authors have

published articles

on the history of the introduction of the pendulum clock.

The most important source of these publications is, almost inevitably, the

extensive standard work Oeuvres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens,(1 for which the editors deserve our respect and

gratitude. We recently found that not all documents kept in the archives have

been noticed or recorded by the editors. This prompted us to re-study the first

period of the pendulum clock on the basis of our own extensive archive research

independent from Oeuvres Complètes, Spring-Driven Dutch pendulum clocks

1657–1710,(2 Catalogue of the Manuscripts of Christiaan

Huygens,(3 and all other publications. Original documents

were examined in the reading room of the University Library of Leiden,(4 in combination with the Codices Hugeniani in

the digital archive of publisher Koninklijke Brill N.V. in Leiden.(5 New, not previously published, finds were

made. Time to entrust our findings to this paper.

The notes of Christiaan Huygens

Huygens’s correspondence and notes It was yesterday exactly a year ago that I made the first model of this kind of clockwork. (Il y eust hier un an justement que je fis le premier modelle de cette sorte d’horloges.) (6

Almost one year earlier, on 12 January 1657, Huygens first mentioned in

the last paragraph of his letter to his mentor Frans van Schooten that

he had recently invented a new construction of a clock driven by weight,

which runs so regularly that he has high hopes it will make the

determination of longitude at sea possible.(7 I really like the news you tell me about Mr Bulliaut’s (8 arrival in these countries, because in addition to what I had to show him in the field of optics, I have a great desire to discuss some specific opinions I find in his work about the astronomy, namely, the comparison of days; I will also share with him a new invention which should be of great use in astronomy and which I hope to use successfully in the search for longitudes. You might hear about it soon.(9

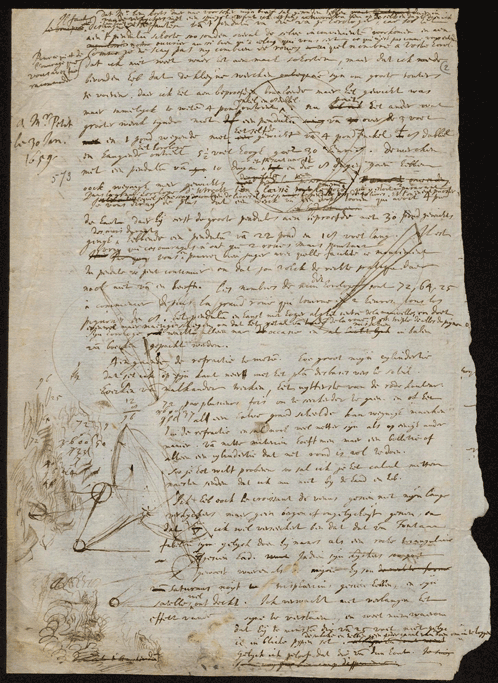

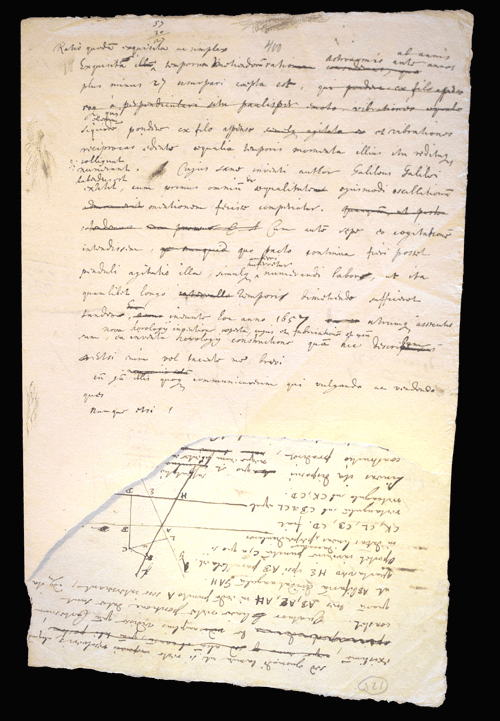

Fig. 1

Example of notes and sketches in a work-copy of a Huygens letter. Leiden University Library, Codices Hugeniani, Hug 45 letter from Huygens to Petit 30 January 1659 (OC II, pp. 326 –29, letter 573). Another, undated,(11. letter from Huygens to the manager of the Leiden Observatory Samuel Karl Kechel, also known as Kechelius, is very interesting. Huygens informs Kechel of the following: (12 The occasion for the invention was provided by the pendulums you have been using for several years. Seeing that, because of the amazing equality of their oscillations, these were ideally suited for measuring time, I started to ask myself whether I could somehow keep their movement continuous and at the same time could take away the inconvenience of counting. I finally came up with the simplest of several ways in which this could be done. I connected the pendulum to the part that regulates the motion through its oscillating movement, called ‘onrust’(13 in our language. However, I did not place this part horizontally, but upright, and let the pendulum hang from a rigid iron bar. When I had done this and then put the weight on the clock, it turned out, just as I expected, that the force of the clockwork aided the individual oscillations of the pendulum, so that instead of gradually weakening into smaller oscillations and finally turning off, they kept going on in a certain deflection. Due to the fact that the oscillations remain equal, the motion of the movement remains equal as well.(14

It is now established that Huygens’s very first design of

his invention is a weight-driven pendulum clock with a vertical balance,

contrary to previous assumptions of a spring-driven balance clock.(15 I am glad that you are perfecting your new clock more and more, and I do not despair that you will make it as good at sea as in your own room, and that the changes of humidity will not alter it more than the change of weights. (Je suis bien aise que vous perfectionniez de plus en plus vostre nouuelle horloge et ne desespere que vous ne la rendiez aussi bonne sur la mer que dans vostre chambre, et que les changements du sec a l’humide, ne l’alteront pas plus que le changement des poids).

From 31 May till 6 June, this is in 6 days, found 2 min. too slow, which is daily 1⁄3 min. Therefore 1⁄6 of a turn added. (Van den 31 Maj. tot den 6 Jun. Dat is in 6 daeghen, bevonden 2' te langhsaem, dat is daeghs 1⁄3 min. Daerom 1⁄6 van een draeij opgezet).(17 This means that a working pendulum clock had been constructed at least by 18 May 1657 and that Huygens was fine-tuning the pendulum. Secondly, it is remarkable that the period between the invention of Huygens on 25 December 1656 and a proven working pendulum clock on 18 May 1657 at the latest was very short. This does not surprise us, because it must have been relatively easy for a clockmaker to turn Huygens’s invention into a working model. If a clockmaker was able to make watches or complicated horizontal table clocks with striking mechanism in the pre-pendulum period, the Huygens pendulum clock with only three wheels (excluding the OP-construction and motion work) is very easy to build. Although Huygens ground his lenses himself, no indication has been found in his extensive oeuvre that he was also capable of making a clock himself. During the above-mentioned period, Huygens lived in The Hague and also stayed there. To construct his clock, it is likely that he collaborated with a local clockmaker with whom he communicated regularly to discuss the progress. In the period 25 December 1656 until the patent was filed, between 1 and 15 May 1657 (see below), there is no indication in Huygens’s correspondence or in his workbooks which clockmaker it might be.

The patent

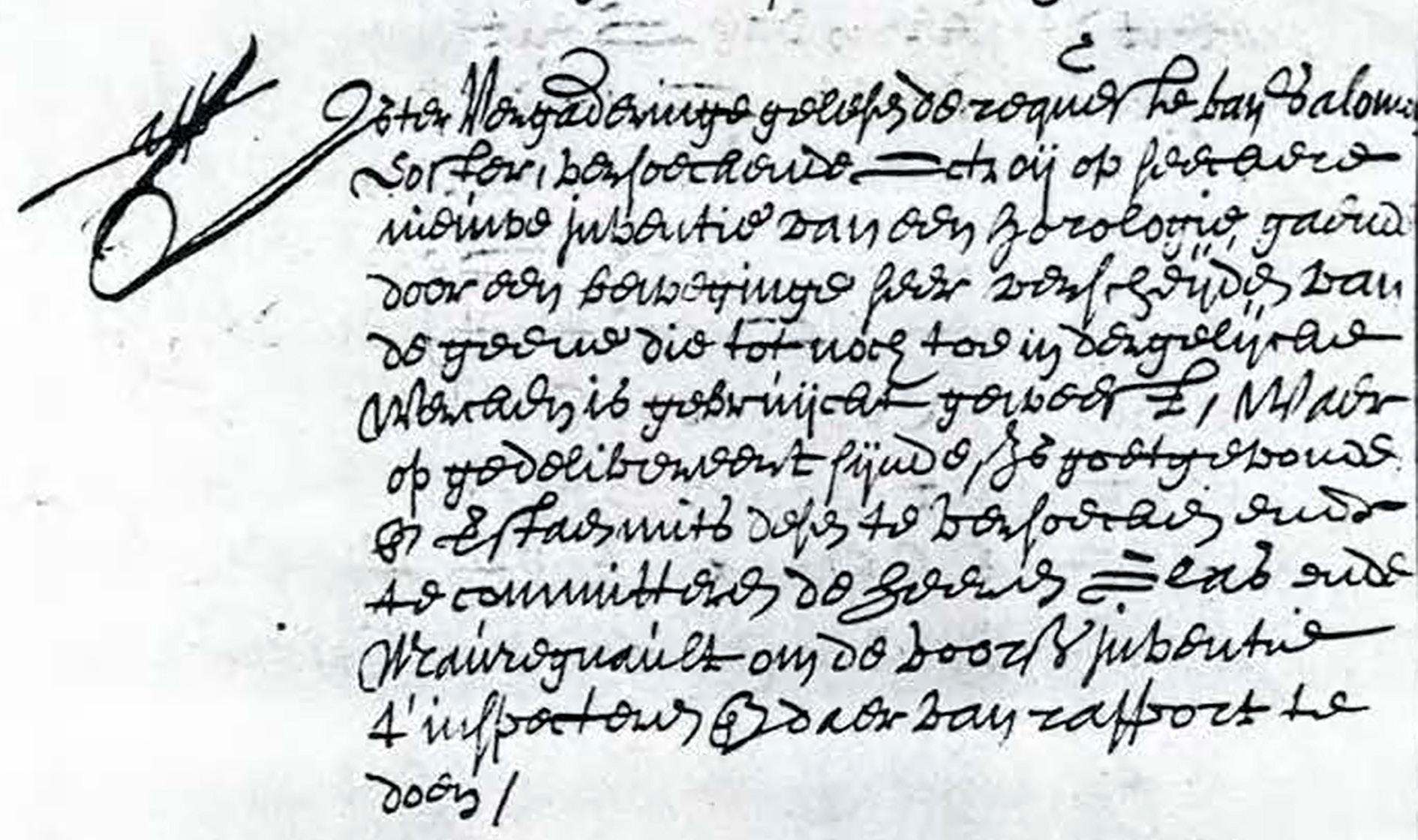

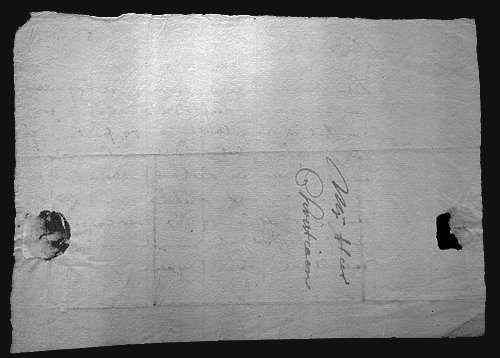

Fig. 2

‘[...] te versoecken

Obviously, they had to inspect a

working Salomon Coster pendulum clock, given the simple fact that Coster

was the applicant for the patent and thus provided the working

invention. As shown in the minutes of the meeting of the States-General

of 16 June 1657 the report of Messrs. Glas and Mauregnault was heard,

after which the application was approved. The patent (privilege or sole

right) was granted to Coster and he received the privilege for 21

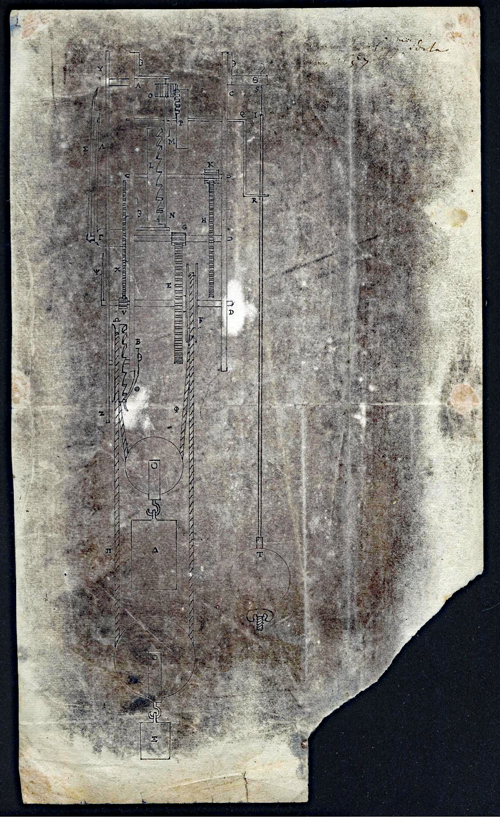

years.(23 Fig. 3

Dr Mart van Duijn of Leiden University Libraries(29

has examined

this document. His conclusions are:

1. The dark side is caused by

rubbing with a dark fabric, which may be dirty but looks like pencil

smudges. My suspicion is that this was caused after the pen drawing

has been applied, possibly because the sheet lay at the bottom of a

pile or was very deliberately swept over it. I don’t think wiping

away an existing drawing created the dark colour.

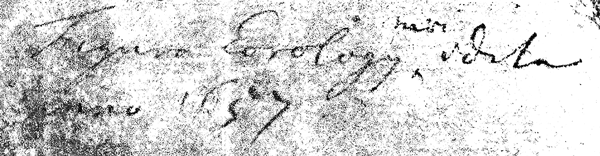

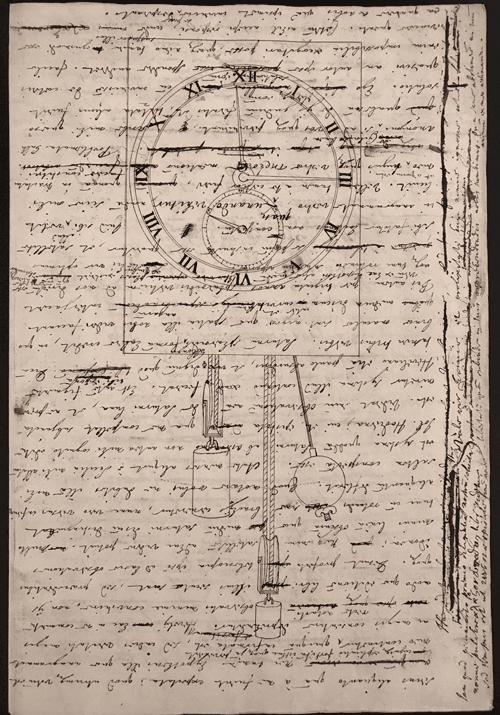

2. There are no signs of correction, wiping or anything to that effect. It is more like hiding the entire page altogether, by making dark streaks on it. 3. The pen note is complete and does not appear to be part of anything that has been corrected or deleted. The fact that the note is difficult to read is most likely due to what caused the dark smudges. It may have been the intention to conceal not only the pen drawing, but also the inscription. 4. There are no indications that there was a pencil drawing underneath the pen drawing. At least that is not visible. On the other side of the sheet there is a pencil drawing of exactly the same clock and it seems that the pencil drawing has been traced from the pen drawing on the other side, or vice versa (see also Yoder). Examination of the illegible part of the inscription on top of the pen drawing with UV-light is unfortunately inconclusive. After learning of Dr Mart van Duijn’s findings, we examined a high-resolution image of the drawing with specialized professional software and discovered the ‘illegible’ word Figura. The complete text of the inscription is Figura horologij mei edita anno 1657 (‘Figure/drawing of my clock made known(30 in 1657’) (Fig. 4).

Fig.4

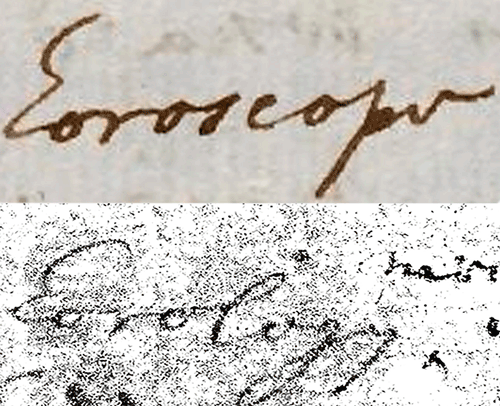

We also compared the handwriting

of the inscription with Huygens’s handwriting in original documents.

For instance the letter ‘h’ of the word horologij looks like a

letter ‘E’. And in a letter to Boulliau of 1 January 1660,(31 Huygens

writes the letter ‘h’ of the word horoscope in exactly the same way.

We can establish that the handwriting of the inscription is the

genuine handwriting of Christiaan Huygens. (Fig. 5)

Examinion of a high-resolution image of the drawing with specialized professional software revealed the previously illegible word ‘Figura’. The complete text is Figura horologij mei edita anno 1657 (‘Figure/drawing of my clock made known in 1657’). Edited by Tom Memel ©.

Fig. 5

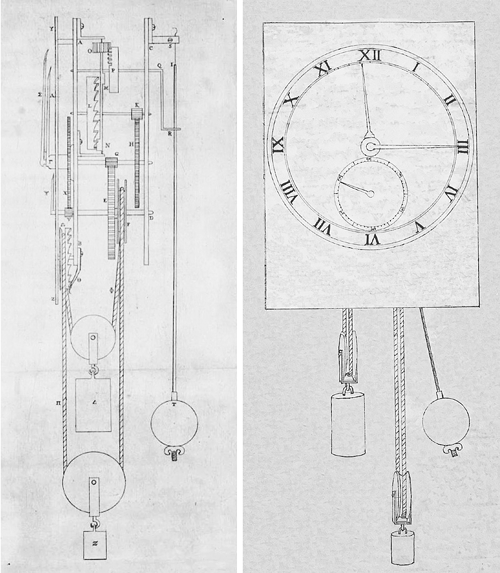

Comparison of Huygens’s handwriting. Edited by Tom Memel ©. So, this is a drawing of Huygens’s pendulum clock with an inscription in his own handwriting and is identical to the illustration that Huygens published in the following year on 6 September 1658 in his Horologium. The darkened drawing shows a weight-driven pendulum clock with hour, second and minute indication, a vertical crown wheel, OP-construction,(32 no cheeks and a ½ second pendulum without a sliding weight. After obtaining the patent in June 1657, Coster

immediately noticed he had to expand the working capacity in his

workshop. The further development with the matching demand for the much

more accurate pendulum clock was expected to become great. In addition,

the regular production as well as the repair of non-pendulum clocks and

watches had to be maintained. At least during this period the apprentice

Christiaan Reijnaerts and of course John Fromanteel worked for Coster.

John Fromanteel is mentioned as a master-servant,(33 but according to the

rules of The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers was still apprenticed to

his father.(34 Fromanteel worked for Coster from September 1657 till May

1658. Fig. 6

The description of the pendulum clock includes its dimensions: ½ braccia

high and 8 soldi wide. In the seventeenth century, sizes were indicated

in Italy by, among others, braccia and soldo (plural soldi).(39 The

dimensions of these units differed per region and even per city. For

Florence, one braccia was equal to twenty soldi. On 2 July 1782, an

amendment to the law increased the length of a soldo in Florence by

17/16 (6.25%) to 29.18 mm. However, before that, one soldo was equal to

27.409 mm and therefore one braccia was equal to 20 times 27.409 mm is

548.18 mm. The dimensions of the case are ½ braccia alto (high) and

eight soldi largo (wide), so 27.46 cm high and 21.9 cm wide.(40 The ebony

case corresponds with the cases of the well-known Coster clocks. The

case has a profiled door, like Coster clocks with alarm and striking

mechanism.

The description states that the movement had a small pendulum (dondolo piccolo). The pendulum of a ½ second pendulum clock has a length of approximately 24.5 cm. Although we cannot determine this with certainty,given the height of 27.46 cm of the case, a short ½ second pendulum could well fit in this small case.

End of this section, click here to

continue.

|

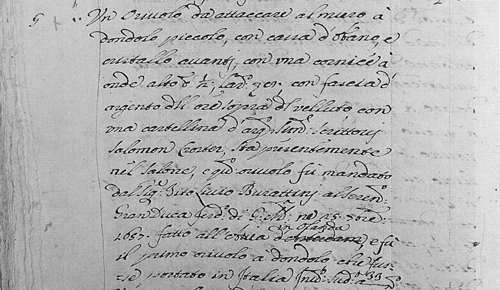

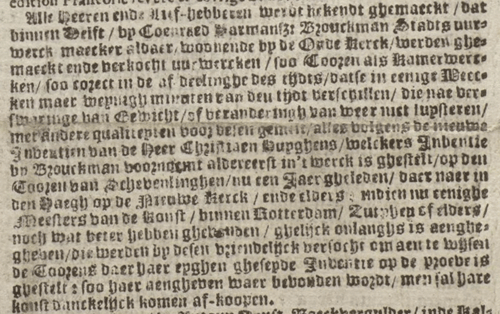

Coster’s advertisement in the Tijdinghe A very important new discovery is a newspaper advertisement that can be seen as the earliest record of dating the production and availability of the pendulum clock for the general public. It can therefore be compared with the well-known advertisement in the Mercurius Politicus of October 1658 in which Ahasuerus Fromanteel announces for the first time that he can deliver pendulum clocks.(41 However, ten months earlier, in a hitherto unknown newspaper advertisement, Salomon Coster announced that he could make and supply various types of pendulum clocks. (Fig. 7)

Fig. 7.

Salomon Coster’s advertisement in the Tijdinghe 51, December 1657. The advertisement appeared in the Tijdinghe uijt verscheyden Quartieren, published in Amsterdam.(42 Its publisher Broer Jansz (1579–1652) was one of the pioneers of the printed press in Holland. The first Tijdinghe appeared in 1619. The weekly edition in question, published by the widow of Broer Jansz, is number 51 and is dated 22 December 1657. As usual in the Tijdinghe, the various messages are printed in chronological order with the oldest news at the top left of page 1. Then, sorted by date, the more recent messages.(43 The last dated message of number 51 is from 20 December 1657. Then, beneath a horizontal line, undated messages are printed, for instance the latest news or an advertisement. The message shows a surprising amount of detail:

In The Hague, at Salomon

Coster’s, are being made and will become available shortly, with a

patent for 20 years, certain kinds of clocks, with springs as well as

with weight, according to the invention of Mr Christiaan Huygens, which

measure time with much more precision and accuracy than until now could

be achieved by any work, because they will be altered neither by changes

of weather or wind, nor by any small imperfection in the spring or the

wheels; also is this invention such that it can easily be added to some

special works already made, in order to make them correct, no matter how

badly they may have run before, and especially very useful for turret

clocks, where it can be added without much trouble depending on the

configuration of the movements: which has already been put to the test.

To be well understood that this all is relevant to hanging and standing

clocks, this invention is not applicable to pocket watches.

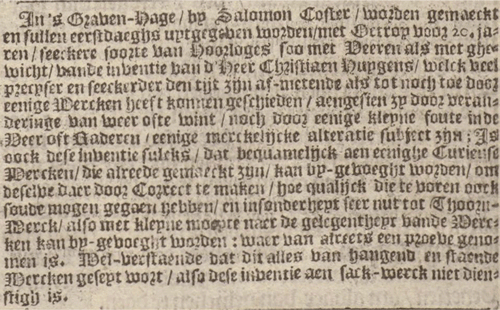

(In ’s

Graven-Hage, by Salomon Coster, worden gemaeckt en sullen eerstdaeghs

uytgegeven worden, met Octroy voor 20 jaren, seeckere soorte van

Hoorloges soo met Veeren als met ghewicht, van de inventie van d’ Heer

Christiaen Huygens, welck veel precyser en seeckerder den tijt zijn

af-metende als tot noch toe door eenige Wercken heeft konnen geschieden,

aengesien zy door veranderinge van weer ofte wint, noch door eenige

kleyne foute in de Veer oft Raderen, eenige merckelijcke alteratie

subject zijn: Is oock deze inventie sulcks, dat bequamelijck aen eenighe

Curieuse Wercken, die alreede gemaeckt zijn, kan by-gevoeght worden, om

deselve daer door Correct te maken, hoe qualijck die te voren oock soude

mogen gegaen hebben, en insonderheyt seer nut tot Thoorn-Werck, also met

kleyne moeite naer de gelegentheyt vande Wercken kan by-gevoeght worden:

waer van alreets een proeve genomen is. Wel-verstaende dat dit alles van

hangend en staende Wercken geseyt wort, also deze inventie aen

sack-werck niet dienstigh is.)

The advertisement shows that the first pendulum clocks for the general public were widely marketed by Salomon Coster by the end of 1657; it is the earliest evidence of that specific moment.

This also shows that Salomon Coster was the first to make all types

of pendulum clocks, both with spring or weight. As further appears from

the advertisement, modifying existing movements with balance or foliot

to pendulum was also an option. Interestingly, the conversion of turret

clocks to pendulum could also be carried out. It is known that the

pendulum tests for the conversion of the movement in the church tower in

Scheveningen took place in exactly the same period.

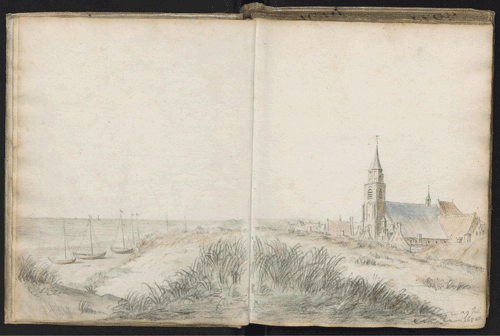

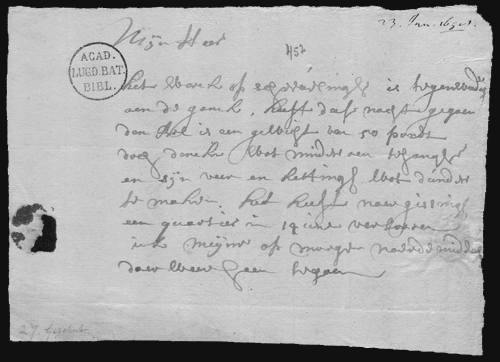

Work on turret clocks by Coster In the period December 1657 / January 1658, Huygens and Coster worked together on the conversion of the movement in the tower of the church in Scheveningen (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8 They did experiments with a long pendulum. In a

note addressed to Huygens of 23 January 1658, Coster writes (Fig. 8a). Mister

Christaen. (Myn Heer

Christiaen

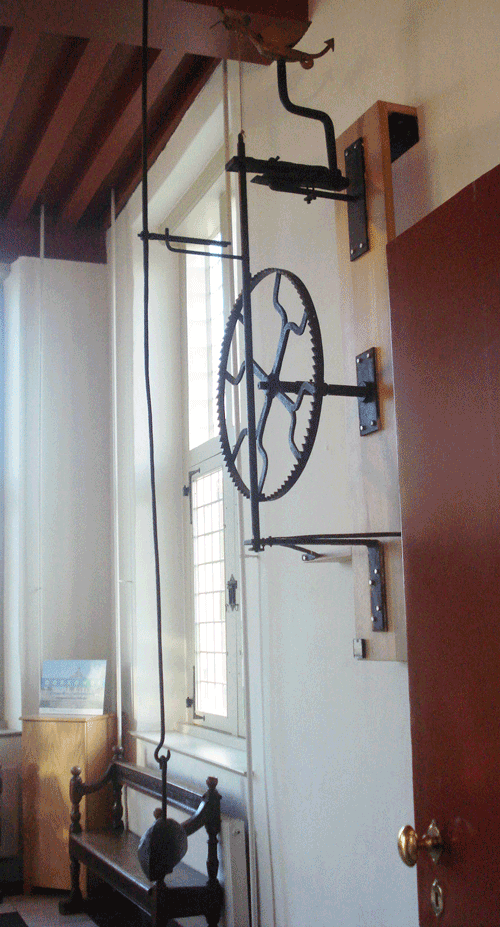

Fig. 8a As a clockmaker for domestic clocks and watches, Coster was unable to forge large parts for turret clocks. For this type of work a turret-clockmaker / blacksmith was sought who could manufacture parts such as the escape wheel and pendulum. In the Oprechte Haarlemsche Courant of 11 February 1659 we found the following advertisement (Fig. 9):

([...] all according to the new inventions of Mr Christiaen Huygens,

which invention for the first time has been applied by Brouckman […], in

the tower of Scheveningen, a year ago now, and after that in The Hague

in the New Church [...].

([...] alles volgens de nieuwe Inventien van de Heer Christiaen Huyghens, welckers Inventie by Brouckman […] aldereerst in ’t werck is ghestelt, op den Tooren van Schevenlinghen, nu een Jaer gheleden, daer naer in den Haegh op de Nieuwe Kerck […]. ) From this we learn that Coenraed Harmansz. Brouckman, turret-clockmaker / blacksmith in the nearby city of Delft, forged the iron parts for the Scheveningen clock tower. This means that the escape wheel, which nowadays is on display in the Museum Hofwijck in Voorburg (Fig 10), was made by Brouckman of Delft. The new movement of the Nieuwe Kerk in The Hague was installed in the tower in May/June 1658.(45 The original timepiece is still present in the church, which means that it is the oldest surviving turret clock with pendulum.

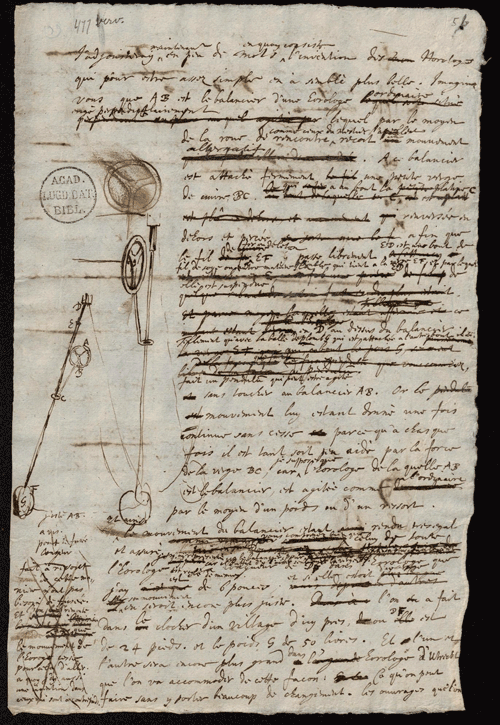

Less than two months after the afore-mentioned advertisement in the Tijdinghe and within a few weeks after the conversion in Scheveningen, it was discussed in the meeting of the Dom Chapter in Utrecht on 19 February 1658 ‘that Coster knows some means to make the clock run accurately’ (dat Coster eenige middelen weet om het Horologie seecker te doen gaan). On 3 May 1658 Salomon Coster was indeed commissioned to convert the turret clock of the Dom Church in Utrecht into a pendulum clock for the sum of 350 guilders. Master blacksmith Bartholomeus Wijnbron, city blacksmith of Utrecht, was commissioned by the Dom Chapter to forge the escape wheel, the pulleys and the hands. The movement was equipped with an OP-construction.(46 For this assignment Coster resided in Utrecht and the work was carried out under his guidance and responsibility.(47 Preparations for Horologium In the Codices Hugeniani we found notes that can be seen as preparation for Horologium, Huygens’s first publication (6 September 1658) of his invention of the application of the pendulum on a clockwork. A good example of this is a working copy in folio format of a letter sent by Christiaan Huygens to R.F. de Sluse dated 13 August 1657.(48 Sebastian Whitestone rediscovered part of this letter for his publication ‘Revelation in revision’ and sees it as a pre-Horologium release.(49 However, it is important to study the entire document, as it is only part of a larger one. The entire document consists of a folded sheet, creating a kind of booklet of four pages. The first two pages are the working copy of the outgoing letter to De Sluse. The letter is closed at the end of page 2 with a greeting, Huygens’s name and the date 13 August 1657. Then page 3 is largely torn off and, upside down with respect to pages 1 and 2, is filled with calculations. This has clearly been used as scrap paper. Page 4, the back of the folded booklet, is known as no. 400 in volume II of Oeuvres Complètes and is quoted by Sebastian Whitestone. It is no more than a note from Huygens, although it is included in Oeuvres Complètes as a separate letter. No. 400 is undated, has no opening or ending and is also upside down with respect to the letter to De Sluse. Pages 3 and 4 were certainly made some time after 13 August 1657. Unfortunately, it cannot be proven when page 4 or note no. 400 were written. It is quite possible that months after writing his working copy to De Sluse, Huygens picked up the letter again and then drafted note no. 400 (Fig. 11). Fig. 11. Draft note no. 400, Codices Hugeniani, Hug 45.

Although the note is interesting, and a nice rediscovery

by Whitestone, the tenor of the text has many

similarities with the introduction to Horologium. We

believe that these are early Horologium thoughts by

Huygens, which he entrusted to paper sometime at the end

of 1657 or perhaps even in the first half of 1658. The

American Huygens expert Dr Joella G. Yoder shares this

view and confirms it in her catalogue.(50

In our research we have found no evidence whatsoever

that there has been an earlier publication before

Horologium. No previous edition of a pre-Horologium

publication is known and Huygens himself has never

referred to it. The correspondence between Huygens and

Chapelain also shows that there was no previous

publication. In the letter from Huygens to Chapelain of

28 March 1658,(51 in recto

Huygens gives a description of his invention for the

first time outside the Netherlands with two sketches of

a vertical balance wheel to which a pendulum is attached

(Fig. 12) and in verso two sketches of the endless cord.

Fig. 12. Letter from Huygens to Chapelain of 28 March 1658, with the two sketches of a vertical balance wheel to which a pendulum is attached. Note the non-cycloid cheeks which are applied to the early balance-pendulum clock. Codices Hugeniani Hug 45.

To protect his rights, Huygens further writes that it is

his wish that his invention will be notified to all his

Parisian acquaintances, because his pendulum clocks are

already shown and sold in Holland. However, on 18 April

1658,(52 Huygens withdraws

his wish to Chapelain and asks for secrecy. Even in

Horologium, where he refers to Coster’s patent of 16

June 1657, Huygens shows that Horologium is the first

publication in which he explains his invention to third

parties.

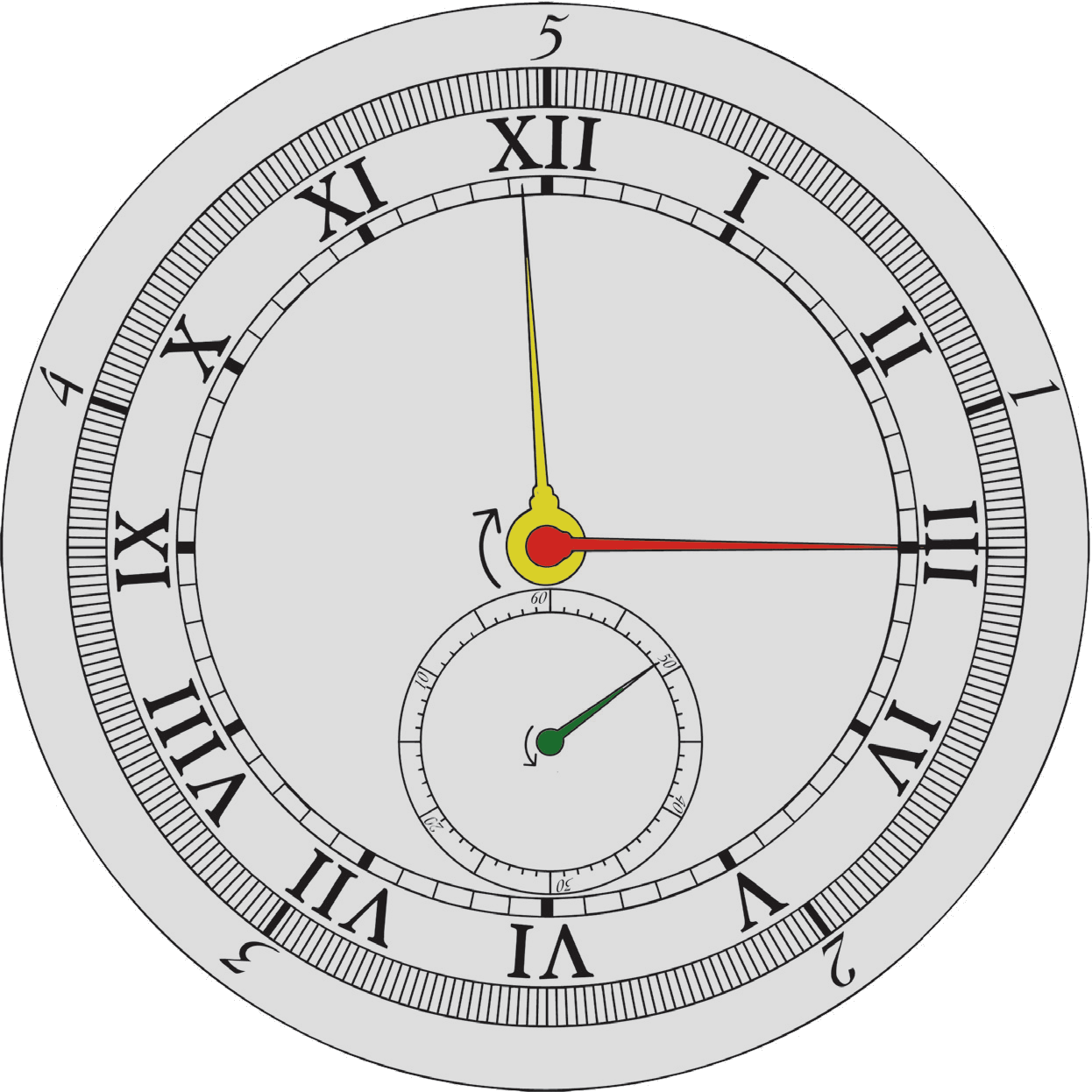

A comparable situation is found on the back of a working copy of the letter sent to Boulliau on 13 June 1658.(53 Here Huygens wrote a first draft of page 3 of Horologium. The text, including cross-outs, corresponds almost literally to the original Horologium. It therefore resembles note no. 400, and, like many notes on Huygens’s outgoing correspondence, is another example of his working method. Horologium Horologium appeared on 6 September 1658. It was distributed to many scientists, high-ranking people and relatives. Salomon Coster was also included in the distribution list as the only clockmaker.(54 Horologium contains a phrase that is important for the development from weight-driven to spring-driven clocks. Thus Huygens writes: ‘We have already found such applications on movements with him, whose labour we have used in making these movements, on movements, set in motion not by a weight but by a spring.’ The editors of Oeuvres Complètes assume that with him is meant Salomon Coster. In our opinion this is indeed most likely, in view of the accumulation of evidence in documents from the period 1657/1658 and the absence of direct contempary evidence of any other clockmaker. According to the above quote, Huygens saw the spring-driven clock at Coster’s workshop and it seems he had only indirectly been involved in this development. This is confirmed by him a few sentences earlier: ‘Much that I could add to this I leave to the ingenuity of the makers, who, once they have understood my invention, can easily find out how it can be applied on the different types of movements.’ The primary importance for Huygens was that the invention was his creation. Although he continued to work on making his clock more accurate, such as the cycloïdal cheeks and later the sea clock and balance spring, the spring-drive was less interesting to him in the early days. In the Codices Hugeniani and in Huygens’s correspondence in the year 1657 we have been unable, after extensive search, to find any documents or drawings of a winding spring or a spring-driven clockwork. All movements that Huygens describes and draws in this period are without exception weight-driven. Only years later, with Huygens’s interest in the development of a sea clock, we find a drawing of a barrel. The Horologium clock After Huygens has listed the most important milestones in the history of timekeeping in the introduction to Horologium,(55 and criticized several persons who wanted to take advantage of his invention, including competitors from abroad, the invention is announced and a clock is described in detail. It concerns a weight-driven pendulum clock with an endless Huygens cord, a large chapter ring with a long central seconds hand, a central hour hand and a separate smaller chapter ring with minute indication. Huygens mentions in Horologium that the pendulum approaches the length of a 5/6 Roman foot (Pes). The length of a 5/6 Roman foot is 24.66 cm. Based on the gear ratio stated by Huygens in Horologium, the length of the pendulum is 24.5 cm, which is very close to the 24.66 cm of the 5/6 Roman foot. The calculated frequency is 7200, which equates to ½ second pendulum. The off-centre minute hand turns counter-clockwise and the central long seconds hand makes one revolution every five minutes. This dial layout is difficult to read for a private user, but this is not important for an experimental clock. After all, it concerned the invention of the pendulum as a regulator. For Huygens, the long central seconds hand was most effective and very practical to register accurately certain scientific observations. We therefore have simulated the layout of the dial using the instructions from Horologium. (Fig. 13).

Many clock lovers know only the side view drawing of the movement in Horologium. However we wondered what the dial from the front view of the Horologium timepiece would look like. It seems we have found the answer. On the first page of a working copy of a letter sent by Huygens to J. Wallis dated 6 September 1658 – publication date of Horologium – an illustration of the layout of a dial is found upside down through the text of the letter.(56 (Fig. 14).

Fig. 14

Dial lay-out on letter Huygens to Wallis 6 September 1658, in Codices Hugeniani, Hug 45. In this case, Huygens first made the drawing of the dial and then used it upside down as a working copy of his letter to Wallis. The drawing is not dated, but must have been made before the date of this letter, as it is unlikely that he would have made a detailed drawing like this over a letter. This drawing of the dial matches almost flawlessly the illustration of the movement in Horologium (Fig. 15).

Fig. 15

Comparison Horologium movement and dial lay-out on letter Huygens to Wallis. Edited by Tom Memel ©. The dial shows a large chapter ring on which the hours are indicated on the inside by means of an hour hand. The seconds are indicated on the outside by a long seconds hand. Inside the chapter ring is a small chapter ring at the bottom at the level of the VI on which the minutes are indicated with a small minute hand. In contrast to the Horologium drawing, the minute indication moves clockwise instead of counterclockwise, while the position of the hands is slightly different. The clockwise rotation of the minute hand can technically easily be achieved by adding an extra wheel in the motionwork, which allows the locations of the hands to change fractionally compared to the Horologium clock. On the other hand, the pendulum length and the position of the weight correspond in the layout of the dial with the Horologium drawing. We calculated the dial sizes on the basis of the assumed pendulum length associated with the half-second pendulum of Horologium. This measures approximately 13.5 cm by 18.4 cm and is therefore slightly smaller than the well-known early Hague clocks. It can be concluded that the layout of this dial is a small improvement / adaptation on the Horologium clock published in September 1658, which formed the basis for the further development of the pendulum clock such as the use of cycloïd arcs, the disappearance of the OP-construction, the introduction of the long pendulum, etc., about which more in a future publication. • Huygens’s very first design of his invention was a weight-driven pendulum clock with a vertically positioned balance. • From the correspondence between Huygens and Frans van Schooten, Mylon and Huygens, Huygens and Kechelius, Huygens and Boulliau, it appears that in the period up to 31 May 1657, the weight-driven pendulum clock was the only subject of discussion. • Between 1 and 15 May 1657, Salomon Coster applied for a patent. • Huygens was in possession of a working pendulum clock on 18 May 1657 at the latest. • On 14 June 1657, two days before the patent date, the clock designed according to the invention of Huygens, for which Coster applied for a patent, had to be inspected by deputies Glas and Mauregnault. This is the earliest direct contemporary evidence of a pendulum clock of a clockmaker.

• Two days later, on 16 June 1657, the patent was

granted to Salomon Coster; he received the privilege for

twenty-one years.

• On 16 July 1657 the States of Holland and West-Friesland granted attachment to Coster and he got the exclusive right to practice the patent in this Province. • The drawing Figura horologij mei edita anno 1657 is the earliest known original drawing of a complete timepiece movement marked by Huygens himself. The drawing is identical to the illustration of Huygens’s weight-driven Horologium clock. This confirms that this clock was the property of Huygens himself and that he already owned it in 1657. • Taking into account the production process and the shipping time, Salomon Coster probably started in mid-July / August 1657 (this is prior to the date of the Coster-Fromanteel contract, i.e. 3 September 1657) the construction of the pendulum clock that was sent on 25 September 1657 by Burattini to the Grand Duke Ferdinand II de’ Medici in Florence. • At the end of December 1657, Salomon Coster was ready to deliver various types of pendulum clocks, both weight- and spring-driven, to the general public. This is confirmed in the newspaper Tijdinghe of 22 December 1657. • At the end of 1657 / early 1658, Huygens started writing Horologium and the notes of these drafts can also be found on the back of the pages in the workbooks of his outgoing correspondence. • In the period December 1657 / January 1658 Coster worked on the conversion to pendulum of the movement in the tower of the church in Scheveningen. Coster kept Huygens informed of the progress. • On 19 October 1658, at the request of Huygens, the Province of Gelderland granted an attachment to the patent to Coster in collaboration with Jan van Call during the landdagsreces of Nijmegen. • Salomon Coster was the only clockmaker to receive Horologium • Horologium shows that Huygens was indirectly involved in the further development of the pendulum clock, such as a spring-driven clockwork, which he left to the clockmaker he used. At that time, Salomon Coster was the only one who had the right to make pendulum clocks. • In the archives, the National Archives in The Hague and the Codices Hugeniani in Leiden University Library, no name of any clockmaker other than Salomon Coster has been found in the period studied. • In the archives, the National Archives in The Hague and the Codices Hugeniani in Leiden University Library, no indication of an earlier Horologium publication was found in the period studied. 1) From the foregoing discussion it can be

concluded that Huygens focussed on the weight-driven pendulum clock with

a long seconds hand. As can be seen from Horologium published in 1658,

Huygens was only indirectly involved in the development of the

spring-driven pendulum clock. We think this development started a few

months after Huygens’s first design of his invention and was left by

Huygens to Coster.

Sept 2021. (This article is subject to ongoing revisions.) Online conversion Fred Kats THF secr.

Rob Memel publications and research Life and work of Nicolas Hanet Further reading on early pendulum clocks. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||