|

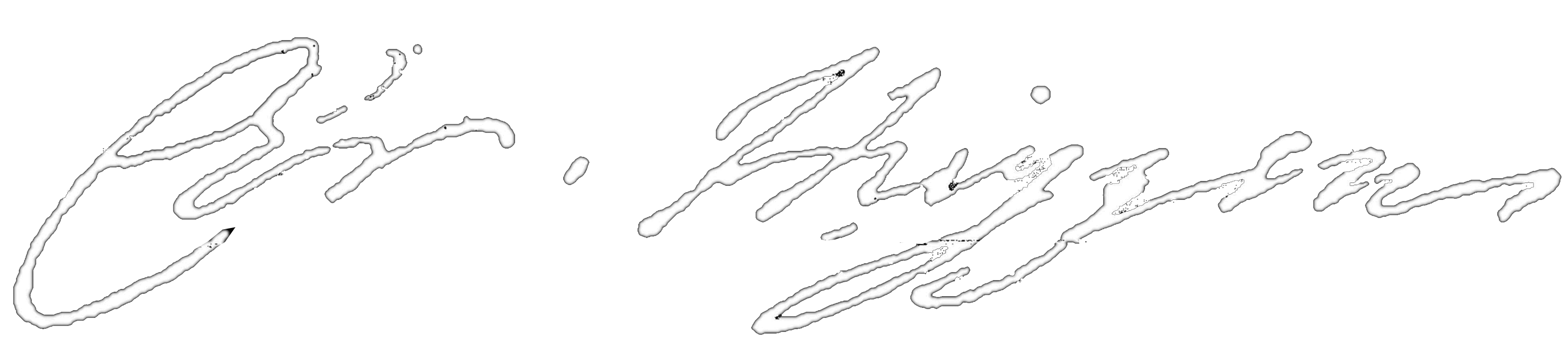

Scrutinizing

Huygens’s

Figura drawing

Mart van Duijn

Ben Hordijk

Rob Memel

Jef Schaeps

(Type

Ctrl+F

to find any text on this page)

After the publication of the

article ‘Salomon Coster, the clockmaker of Christiaan Huygens’ the authors

decided to have the enigmatic Figura horologij mei edita anno 1657-drawing

examined by the Leiden University Libraries. The investigation revealed that the

Figura drawing had been made for the printing of the image in Huygens’s

Horologium, published in 1658.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

By BH and RM

In

2018 we had planned to study the correspondence of Christiaan Huygens at Leiden

University Libraries. Already during our first visit to the reading room we came

across two interesting finds, a drawing of an unknown clock dial and a drawing

of the profile of a pendulum clock movement. The latter drawing is darkly

coloured and drawn in ink on one side (Fig. 1) and traced in pencil on the other

(Fig. 2). This drawing is now known as the Figura horologij mei edita anno

1657-drawing (hereafter Figura drawing). We immediately associated both the dial

drawing and the Figura drawing with Huygens’s Horologium image of 1658 (Fig. 3),(1

the first pendulum clock publication of Christiaan Huygens. After researching

the Oeuvre Complètes,(2

and other

literature and publications, we noticed that neither of the drawings had been

depicted previously. Joella Yoder catalogued and briefly described both drawings

in her book A Catalogue of the Manuscripts of Christiaan Huygens,(3

but neither is

depicted there. The Figura drawing in particular intrigued us because of its

similarity to the Horologium clock, the handwritten text and the possibility of

new insights into the early development of the pendulum clock.

After

discovering all kinds of other documents, we decided to make a publication about

the invention and manufacture of the early pendulum clock during the period 1657

– September 1658.(4

For us it was a necessity to work as much as possible with

primary sources from the seventeenth century. The use of secondary sources from

the eighteenth century and later, we considered as highly undesirable because of

the strongly diminishing reliability of information. The relevance of later

secondary sources is in our view only suitable when it unquestionably supports

an explicit primary source.

Prior to the publication, we asked Dr Mart van

Duijn to carry out an initial inspection of the Figura drawing. The results were

included in the aforementioned publication. After our publication, and the

comments published in the next journal issue,(5

we decided that

the Figura drawing needed more and extensive in-depth study. At our request Dr

Mart van Duijn and Drs Jef Schaeps agreed to perform a new extensive in-depth

inspection of the Figura drawing. Their findings are presented in the next

section.

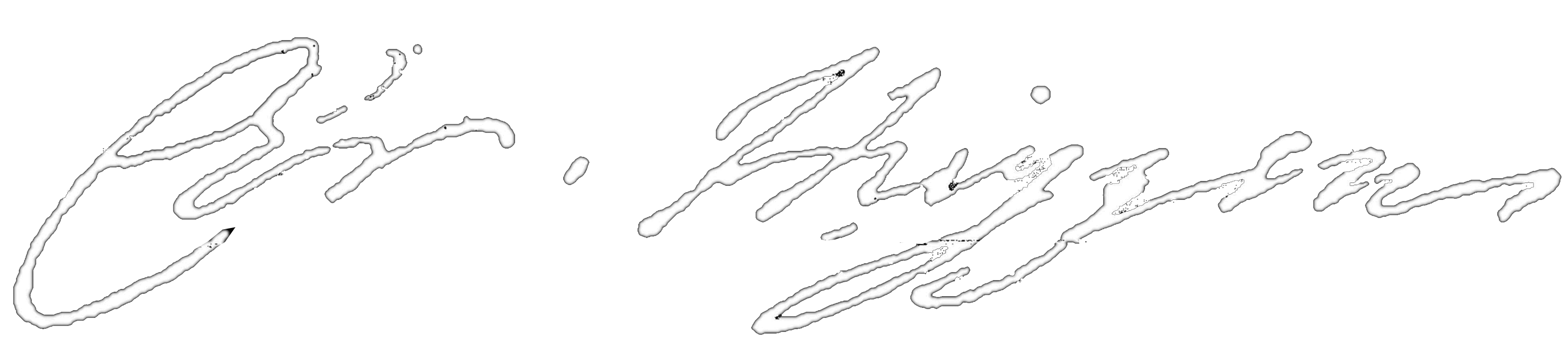

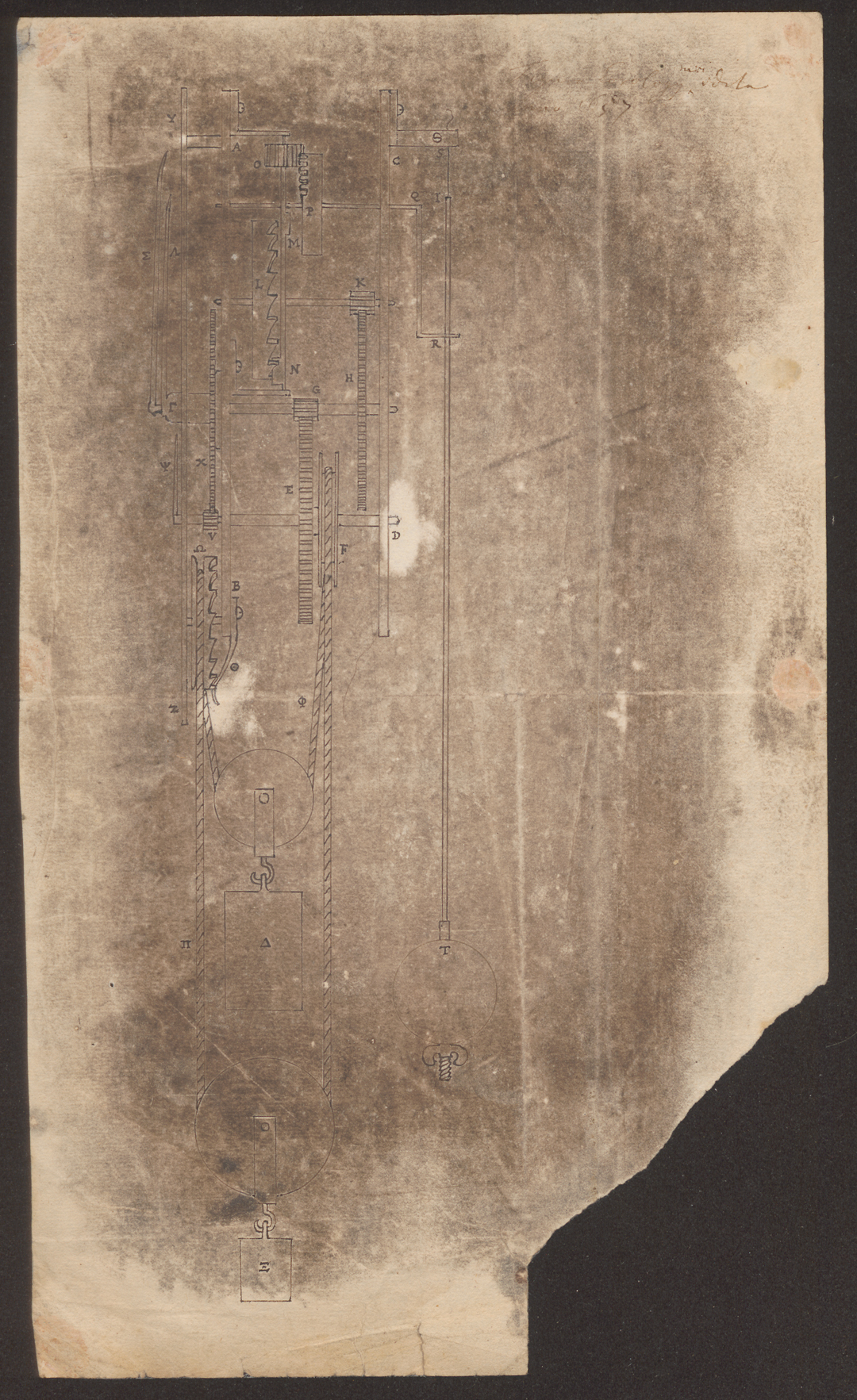

Fig 1.

The verso side of Codices Hugeniani, HUG 32 folio 188

(Leiden University Libraries), showing a drawing in ink of the profile

of a pendulum clock with on top right the inscription Figura horologij

mei edita anno 1657 (A drawing of my clock made known in the year 1657).

The dark surface is caused by the etching ground of the copperplate

which was used to print the Horologium image.

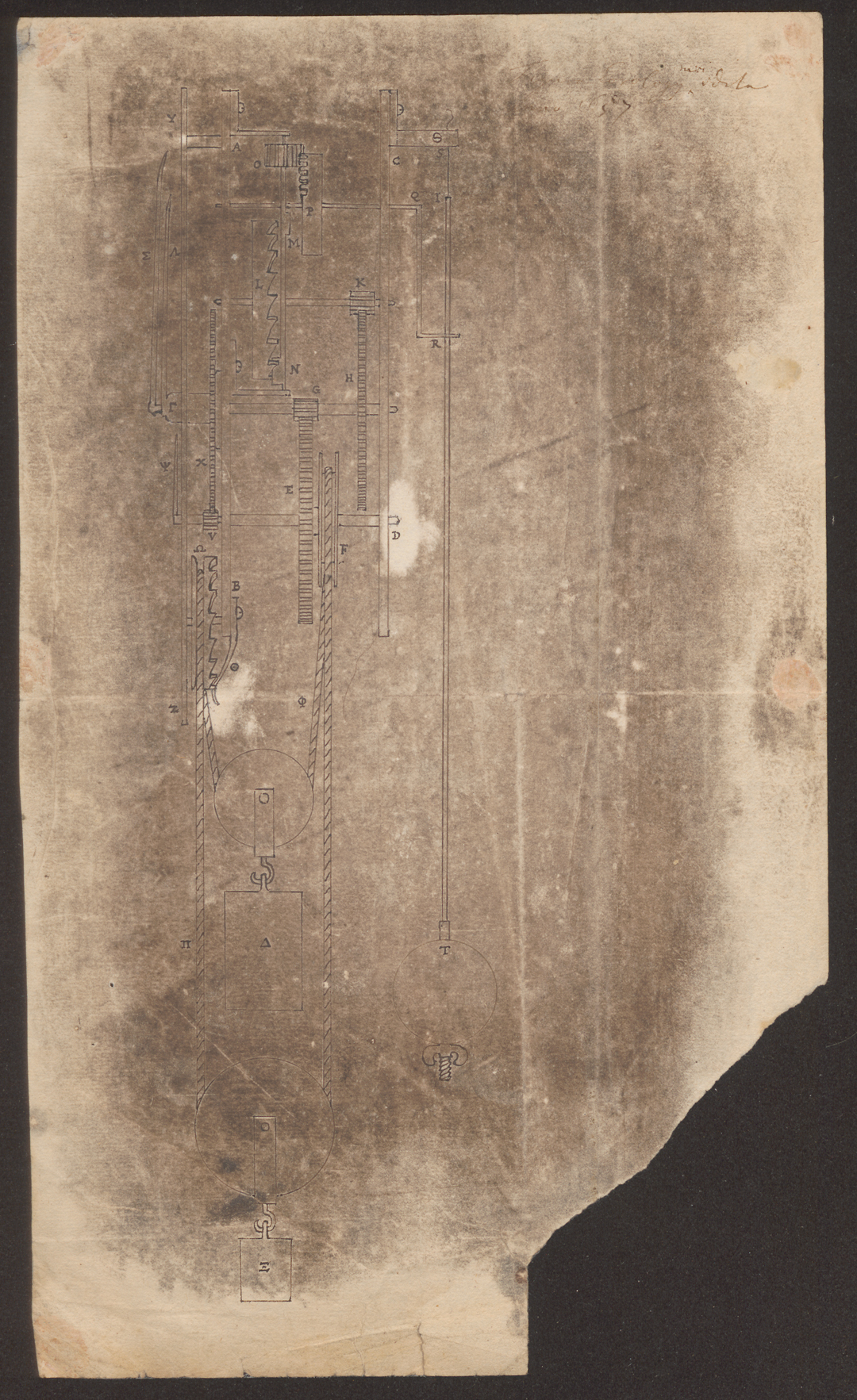

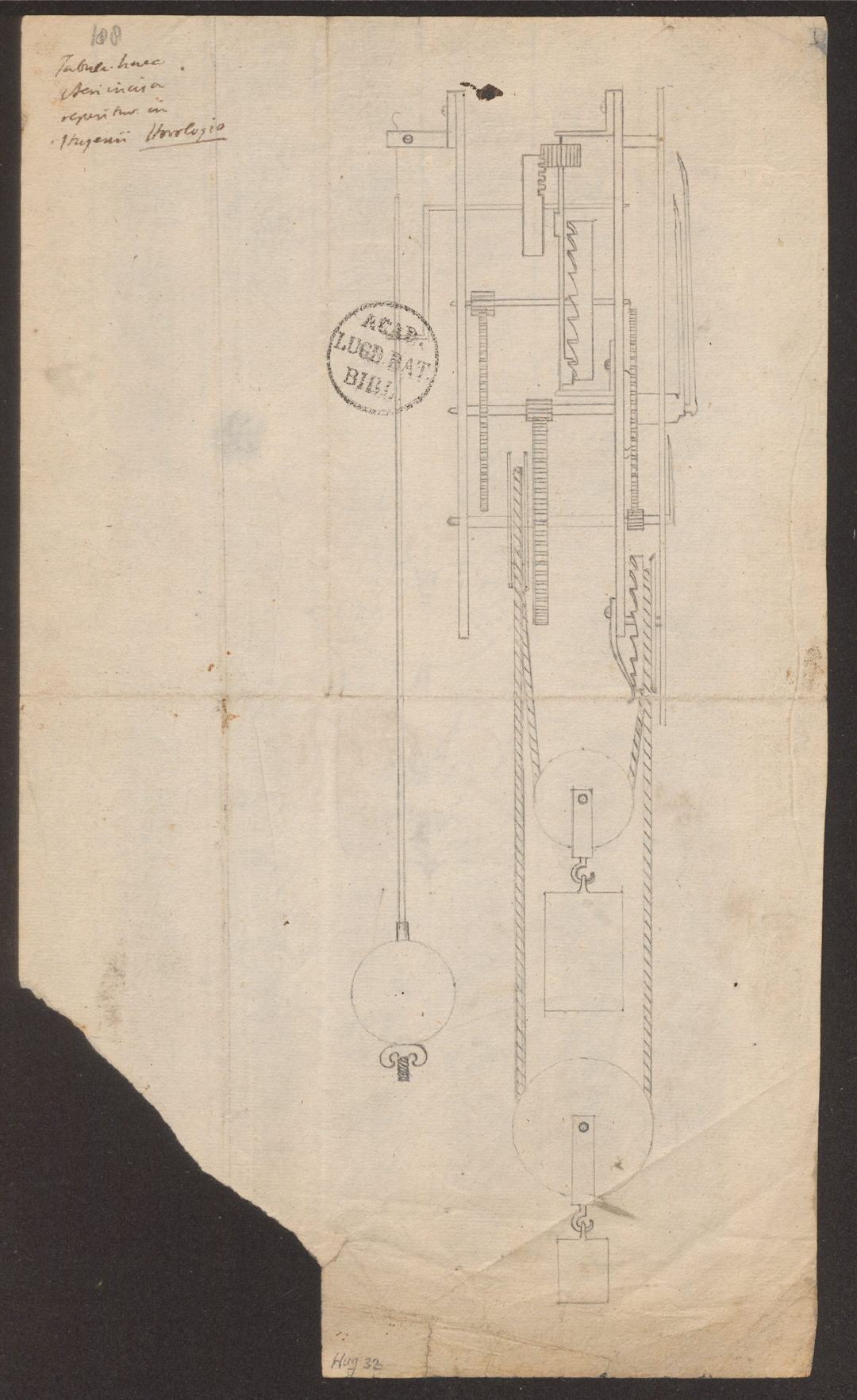

Fig 2.

The recto side of Codices Hugeniani, HUG 32 folio 188

(Leiden University Libraries), showing the mirrored drawing in pencil

which is traced from the ink Figura drawing on the verso side (see Fig

1.). On the top left the inscription Tabula haec Aeri incisa reperitur

in Hugenii Horologio (This drawing, incised in copper, is found in

Huygens’ Horologium).

Click to enlarge

THE RESEARCH OF THE FIGURA

DRAWING

THE RESEARCH OF THE FIGURA

DRAWING

By MvD and JS

HUG

32, fol. 188, is part of Huygens’s extensive archives kept at Leiden

University Libraries, mostly containing his scientific workbooks and

correspondence. HUG 32 is described by Yoder as a collection of loose

sheets of various sizes and dates, called Portefeuille Varia [1] by the editors of the

Oeuvres

Complètes. Most of the material was written by Christiaan’s primary

heir, Constantijn Huygens Lz; only ff. 168–192 are in Christiaan’s hand.

Unlike most of the material in Huygens’s archives, which was bequeathed

to the library after Huygens’s death in 1695, HUG 32 was gathered by the

lawyer and collector Jean Theodore Royer (1737–1807) and willed to the

library in 1809.(6

Fig 3.

Image of the Horologium (1658) clock from the collection

of the Leiden University Libraries (539 F 29). This copy belonged to

Isaac Vossius, who received Horologium directly from Christiaan Huygens.

The sheet in question measures 290 by 172 mm, with one of the lower

corners torn off, and has a modern foliation in pencil. The verso side

has the Figura drawing in ink, with letters indicating the

different parts of the pendulum clock. The upper right corner has a

barely legible inscription, by Huygens himself: Figura horologij mei edita anno 1657

(A drawing of my clock made known in the year 1657). Yoder was unable to

decipher the first word, but Ben Hordijk and Rob Memel managed to

publish a complete and convincing transcription in their article (see

note 4). The ink drawing is covered with a greyish residue of etching

ground, resulting in a somewhat darkened image. This darkening is not

the result of the erasure of another or earlier drawing, as has been

suggested. The recto side of fol. 188, bearing the stamp of Leiden

University Libraries, has the Figura drawing in graphite (pencil). The

upper left corner has a seventeenth-century inscription: Tabula haec

Aeri incisa reperitur in Hugenii Horologio

(7

(This drawing, incised in copper, is found in Huygens’s Horologium). The

drawings on both sides exactly align, probably the result of the ink

drawing on the verso side being traced in pencil on the recto side.

Although the modern foliation might suggest otherwise, the image in ink

was done first, followed by the tracing in

pencil.

End of this section, click here to

continue.

NOTES

NOTES

|

|

|

|

1 |

Christiani

Hugenii a Zulichem Const. F. Horologium (The Hague, Adriaan

Vlacq, 1658).

|

|

2 |

Oeuvres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens publiées par la Société

Hollandaise des Sciences (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 22 vols,

1888–1950); hereafter: OC. |

|

3 |

Joella G. Yoder, Catalogue of the Manuscripts of Christiaan

Huygens Including a Concordance With His Oeuvres Complètes.

History of Science and Medicine Library, Volume 35

(Leiden-Boston: Brill, 2013). |

|

4 |

‘Salomon Coster, the clockmaker of Christiaan Huygens. The

production and development of the first pendulum clocks in the

period 1657 – September 1658’, Antiquarian Horology 42/3

(September 2021), 323-344. |

|

5 |

Letters to the Editor in Antiquarian Horology 42/4, 576-580. |

|

6 |

Yoder, Catalogue of the Manuscripts of Christiaan Huygens, p.

143. |

|

7 |

With ‘Aeri’ instead of ‘iteri’ as transcribed by Yoder. Thanks

to Jos van Heel (former curator old collection Museum Meermanno

The Hague). |

|

8 |

For a detailed description of the process see Ad Stijnman,

Engraving and etching, 1400– 2000: a history of the development

of manual intaglio printmaking processes (London/Houten, 2012),

pp. 155– 157. |

|

9 |

Studied copy: Leiden, University Library, 539 F 22 (copy of

Isaac Vossius). |

|

10 |

Yoder, Catalogue of the Manuscripts of Christiaan Huygens, p.

145. |

|

11 |

A construction to minimize the amplitude of the pendulum by

adding a pinion and a wheel, in the Figura/Horologium drawing

marked O and P. Huygens also experimented with non-cycloid arcs

in the early phase. Both the OP construction and the non-cycloid

arcs no longer exist with the invention of the cycloid shape at

the end of 1659. |

|

12 |

Codices Hugeniani, HUG 45 letter Huygens to Kechelius June 1657

(OC II, letter no. 392) and Codices Hugeniani, HUG 45 letter

Huygens to Chapelain 28 March 1658 (OC II, no. 477). |

|

13 |

Christiani Hugenii Zulichemii Const. F., Horologium

oscillatorium sive de motu pendulorum ad horologia aptato

demonstrationes geometricae (Paris, F. Muguet, 1673). |

|

14 |

See, among others, in La veuve Estienne & Fils, Le Spectacle de

la Nature (1756) and Benjamin Martin, A new and comprehensive

system of mathematical institutions, agreeable to the present

state of the Newtonian mathesis (1764). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Authors: |

Dr. Mart van Duijn (MvD) is Curator of

Post-Medieval Western Manuscripts and Archives at Leiden University

Libraries.

|

Drs. Jef Schaeps (JS) is Curator of

Prints and Drawings at Leiden University Libraries.

|

Ben Hordijk (BH)

is the former chairman of the Museum and

Archive of Horology and founding member of the Horological

Collection Netherlands.

|

Rob Memel BA (RM) Rob

Memel is a restorer of early clocks and complicated pendulerie with

an interest in seventeenth-century Horological archive research.

Address for correspondence: info@robmemel.nl |

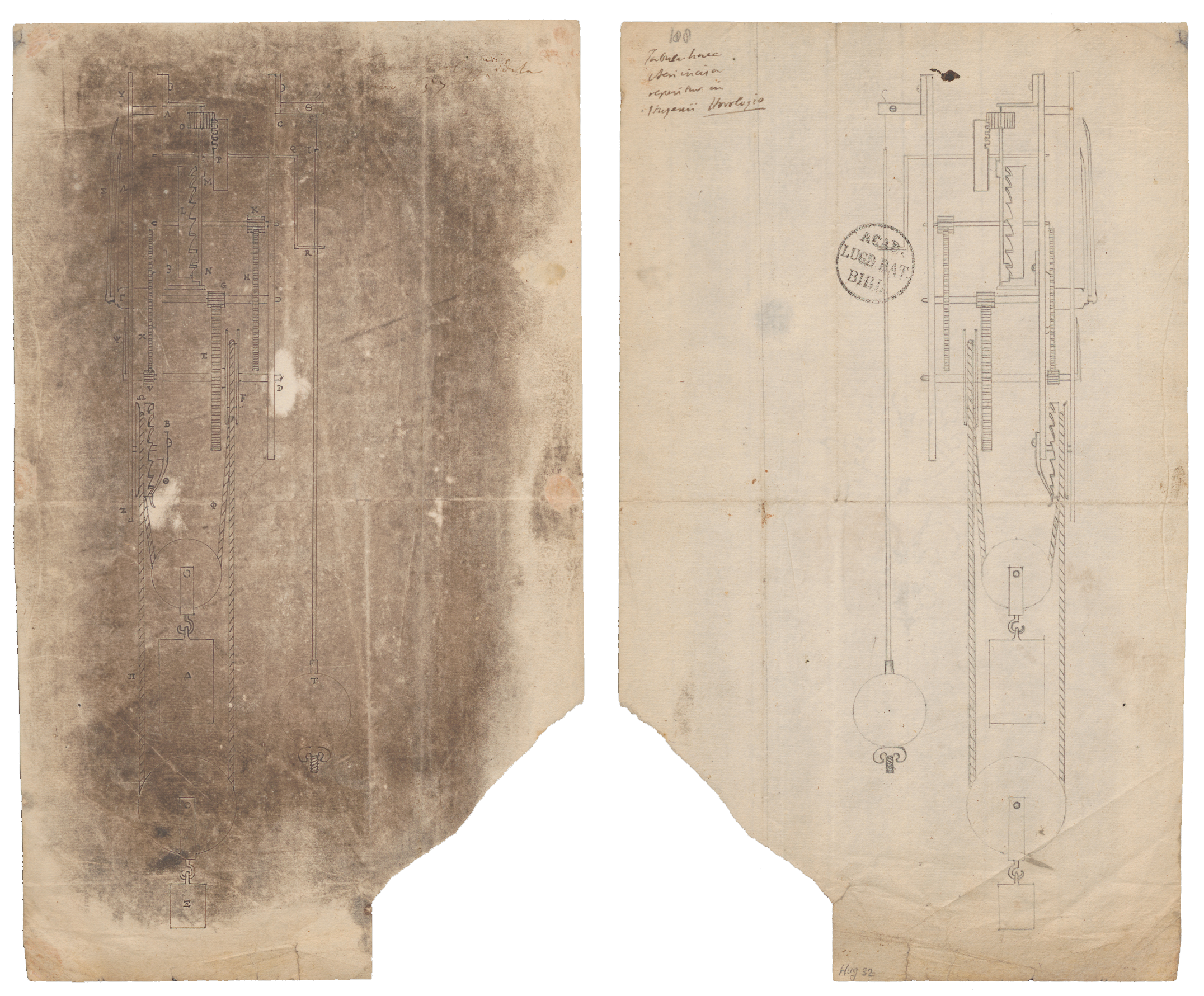

The residue of

etching ground seems to point to a very common technique, used for

transferring images to a copper printing plate. In general this process

entails placing a drawing on a copperplate covered with etching ground

(wax containing a pigment such as sooth or graphite), after which the

drawing was retraced with a sharp object, indenting the etching ground.

To avoid a mirrored reproduction of the design, a preceding step was

necessary in which the drawing was first traced on the back of the

sheet. This is what has been done with Huygens’s Figura drawing in ink,

with the back of the drawing now being identified as the recto side. The

indentations are still visible (Fig. 4).

Fig 4.

Detailed image of the recto Tabula drawing (see

Fig 2). The indentations are usually on the pencil line, which

makes it difficult to show in an image. Here the indentations

are just beside the pencil line. Between the yellow lines is

the traced pencil line. Between the red lines the indentations

to make a transfer onto the copper plate.

After the drawing had been

transferred onto the plate, this was etched in order to produce a

printing matrix.(8

A drawing by Huygens used to transfer a design to a printing plate is of

the utmost rarity. No other example is known from Huygens’s archives

kept in Leiden. This kind of drawings usually perished in the transfer

process.

Comparing the Figura drawing to the image in Huygens’s

Horologium, as is suggested in the anonymous inscription on the recto

side, reveals the fact that the drawing and the printed image are

identical, with the exception of the letters (Latin and Greek), that

were probably added to the plate separately

(9

Yoder refers to the ink drawing as an exact copy of the Figure used in

Horologium,(10.

while in fact the ink drawing on HUG 32, fol.

188 verso, is the original design used to create the printed image of

Huygens’s pendulum clock in Horologium (1658) (Fig. 5).

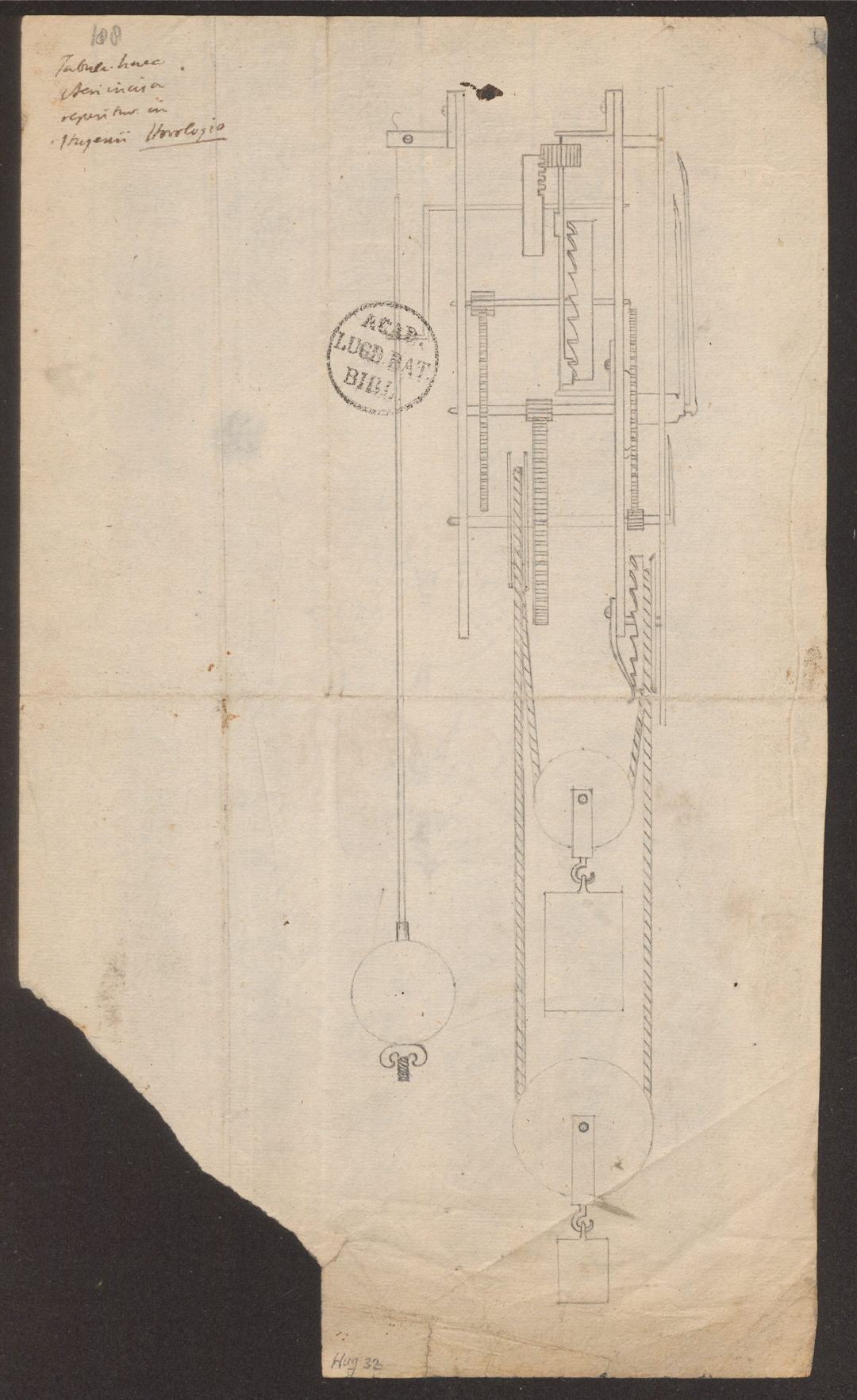

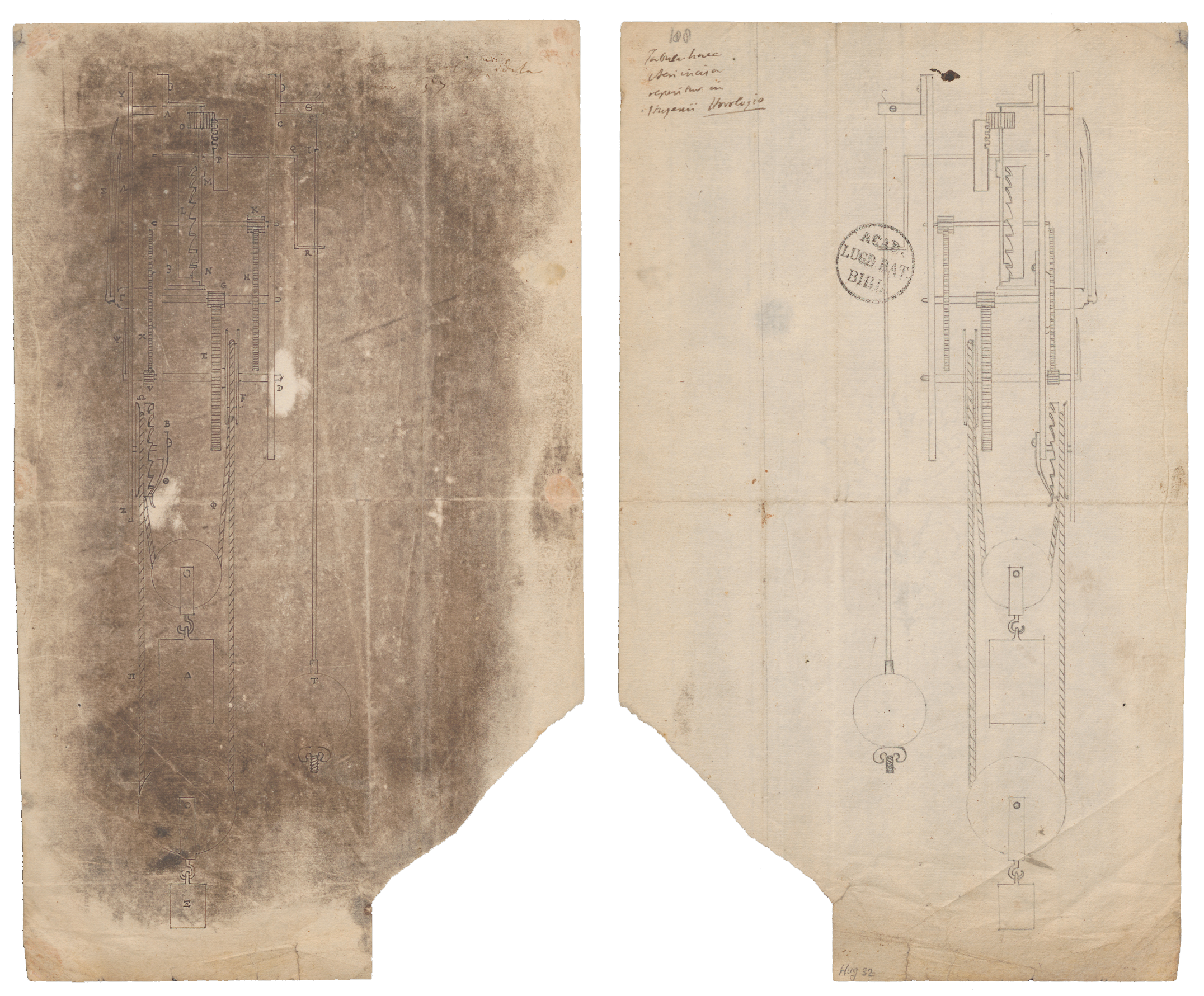

Fig 5.

From left to right the process of

the Figura ink drawing, the traced mirrored Tabula

pencil drawing to the final image in Horologium

(1658).

Shortly

before his death in 1695, Huygens donated a significant part of his

scientific treatises

to the University Library in Leiden. After 1800 this legacy was further

enriched with family-owned manuscripts and letters. The personal archive

of Christiaan Huygens has been brought together in the Leiden University

Library in the so-called Codices Hugeniani and is digitally available.

These Codices Hugeniani are collected in fifty-two volumes and contain

notes and folders with loose texts in the fields of astronomy,

mechanics, mathematics and music, as well as annotated books and sent /

received correspondence. At the top of the pages of the original letters

of Huygens the editors of Oeuvres Complètes added in pencil their own

method of numbering the letters, which matches the letter numbers in Oeuvres Complètes as contained therein. For clarification and

traceability we added the OC numbering in the footnotes as well.

In

order to gain a better understanding of the following, it is important

to know that before Huygens sent a letter to one of his contacts, he

first wrote a draft or working copy. The primary purpose of this working

copy was to organize his thoughts and make improvements when necessary.

Once this was to his liking, Huygens wrote the letter in a final version

to send it out. He kept the working copy for himself so that he could

reread it later. The working copies of Huygens’s outgoing correspondence

are thus located in Leiden, while the same letter in the final version

may be kept elsewhere, for instance in Paris.

The original documents

of the University Library in Leiden show that Huygens consistently and

frequently used his working copies of letters as scrap paper for notes,

sketches and points of interest. Especially the back, but also the

margin of the copy was used (Fig. 1). These notes are not always

included in Oeuvres Complètes and can provide new presumptive evidence

to the history of the development of the pendulum clock.

FIGURA

AND THE DEPICTED CLOCK FIGURA

AND THE DEPICTED CLOCK

By BH and RM

Huygens made many sketches of clocks and parts of clocks that are

interesting for closer research. Unfortunately most of these sketches

are undated which makes it difficult to date them in a specific

year/month. Drawings by Huygens, like the Figura drawing, are extremely

rare certainly when it concerns the original drawing which was used as a

transfer on a copper plate for Huygens’s Horologium. Because of the text

Figura horologij mei edita anno 1657 on the verso side in Huygens’s own

handwriting, it is certain that the design of the clock, including the

OP construction,(11.

vertical escapement wheel, the absence of the arches, the Huygens

endless cord and the central seconds hand existed at the latest in

December 1657. Also, the handwritten text on the pencil tracing clearly

indicates that Huygens used a copper plate for his Horologium

publication. Unfortunately, Huygens did not add a specific month to his

text. December 1657 is therefore the most cautious estimate, but in

theory it could also be January 1657. We consider the latter less likely

since the first design of Huygens’s clock was a pendulum linked to a

vertical balance.(12

That the Figura movement could have been the movement from Coster’s

patent application is an option, but we would like to emphasize that

there is no evidence for this. It is even questionable whether a drawing

was included in the patent application at all, since the existence and

ultimate proof of such a drawing is completely lacking.

Images

in Horologium and Horologium Oscillatorium Images

in Horologium and Horologium Oscillatorium

By BH and RM

It is

impossible to say with certainty when Huygens made the Figura drawing.

As the clock as such already existed in 1657, it is a promising

possibility that the drawing was also made in 1657. We know that Huygens

started writing Horologium by the end of 1657 and that the process from

the delivery of a manuscript to a printed copy could take months in the

seventeenth century. Nevertheless, we can establish that the Figura

drawing is the earliest existing accurate drawing of Huygens’s pendulum

clock.

In 1673, Huygens published Horologium Oscillatorium,(13

his second publication on clocks. This publication also contains an

image of a clock (Fig. 6).

Fig 6.

Image of the Horologium

Oscillatorium (1673) clock from Huygens’ own copy

which is part of the collection of the Leiden

University Libraries (755 A 5).

The clock in this image is equipped with the

cycloidal arcs that Huygens writes about extensively. Huygens invented

the cycloidal arcs by the end of 1659, and clocks (almost) identical to

this image were unmistakably manufactured from December 1659 onwards.

Particularly in the eighteenth century, publications were issued in

which the clock image from Horologium Oscillatorium was used as a basis,

and the author in question produced his own woodcut or engraving

etching.(14

That Horologium and

Horologium Oscillatorium were regarded by Huygens as his earliest two

treatises on clocks is obvious. In Horologium Oscillatorium Huygens

makes two clear references to his earlier and first publication

Horologium. In his opening sentence in typical muddled

seventeenth-century language, he writes:

It is the sixteenth year since

we published a pamphlet about clocks, then recently invented by us.

By the

sixteenth

year Huygens means the year 1658, where 1658

is the first year and 1673 the sixteenth year.

This translation and accompanying explanations are

supported by experts of Leiden University

Libraries. Some authors misinterpret this sentence

and mistranslate it as it is sixteen years ago,

resulting in the year 1657 which is clearly

incorrect. In Horologium Oscillatorium Huygens reconfirms the

year 1658 in a number of sentences after the opening sentence:

Sixteen years ago [1657, BH/RM], when neither in words nor in writings

had anyone mentioned clocks of this kind, or in general any rumor was

spread (I am talking about the use of the single pendulum employed in

timepieces, for nobody will dispute the addition of the cycloid), I

invented its construction by my own thinking and had it realized. In the

following year [1658, BH/RM], which was the fifty-eighth of this

century, I published the image of the automaton and the description;

copies of both the movement itself and the booklet I sent in all

directions.

In contrast to the sixteenth year

in his opening

sentence, Huygens does write here sixteen years ago which is

1657. In that year Huygens indeed ...invented and had the construction....

realized, in which the first clocks were manufactured by Salomon

Coster.

In the year after, which was the fifty-eighth of this

century, I published the image of the automaton and the description.

Here Huygens clearly refers to the

Horologium image being the image of

the automaton followed by the description being Horologium, Huygens’s

first publication in the following year 1658.

(This article is subject

to ongoing revisions.)

First published by The Antiquarian Horological

Society in: Antiquarian Horology, Number two, Volume

forty-three, June 2022. p.208-213.

LINKS

LINKS

Chr.

Huygens' Œuvres Complètes.

(pdf)

Chr. Huygens Horologium 1658.

(pdf)

Early pendulum

|