|

The

Identification and Attribution

of

CHRISTIAAN

HUYGENS'

First Pendulum

Clock.

(a

(Type

Ctrl+F

to find any word on this page)

INTRODUCTION

It is an awkward irony, to be obliged to begin by advancing a

proposition which contradicts some of the studies on which it itself is

based. Here, in identifying and attributing Christiaan Huygens’ first

pendulum clock, it is necessary to dismiss the notion that his first

clockmaker was Salomon Coster (1620-1659) or that he developed his

invention without using a clockmaker at all. Both assumptions, though

flawed, are revealing and examination of them provides the best

introduction.

NOT ALONE

Huygens mentions no clockmaker in connection with the development of his

innovation. However, it is most unlikely that he would have launched his

paradigm change in a centuries-old craft without experimenting on the

purpose- made product of a practitioner. To have done so would be

contrary to the quantitative method of this great empiricist. He

required precise values. In this case he needed to know the scope and

limits of his invention before divulging it. Huygens dates his invention

to December 25 1656.(1

This date

should not be regarded as marking an Archimedean inspiration on the

basic principle of pendulum control. In fact, although it has often been

said that he applied the pendulum to clockwork, it is perhaps truer to

say that he brought clockwork to the pendulum. His original intention

was, in part, to relieve astronomers from the task of impelling and

counting the oscillations of the manual pendulum then in use for timing

observations(2

Having realised how this could transform clockwork he

would surely have commissioned a specially transformed clock. Christmas

day 1656 therefore, probably signifies the completion of the last

missing element of a tried and tested machine. Nothing less than the

high performance of such a machine would have allowed Huygens to reveal

immediately to others, his hopes of solving the longitude problem(3. By

the beginning of 1657 he must have achieved a roughly two orders of

magnitude increase in accuracy over pre-pendulum timepieces, obtaining

results to within a few seconds per day. How else could a mathematician

flatter himself that his invention was immanently relevant to maritime

longitude? Apart from longitude he urgently required the best possible

timepiece for his astronomical observations, for his studies of

accelerated motion and his search for the constant of gravitational

acceleration where his conical pendulum later provided the key. Logic

alone therefore suggests that when Huygens realised the potential of a

pendulum escapement, he commissioned the finest machines possible with

which to experiment further.

●

There is evidence that confirms what logic supposes. Firstly there are

the material results of this experimentation in the refinements he

developed before obtaining a patent: maintaining power, optimal gear

train, pendulum crutch with flexible suspension and isochronal cheeks(4.

These considerable intricacies required professionally made machinery

and lengthy experimentation. Many months would be needed to evaluate the

Flemish astronomer GodefroyWendelin’s (1589- 1667) proposition of

seasonal variations alone(5. Secondly there is written evidence.

On the

1” November 1658, he distantly recalls in a

letter to Pierre Petit, (1598-1677):

|

...at

first I suspended the pendulum between two curved plates

...

,which by experiment I learned ... how to bend...

And I remember having so well adjusted two clocks in this manner

that in three days they never showed a difference of even

seconds although in the meantime I often changed their weights

rendering them heavier or lighter

(6.

|

It is tempting to speculate that it was the empirical perfection of

these isochronal cheeks that was commemorated on the

25 December 1656. To one of the finest geometers of his age, the resolution of what must

have been for him the ugly inconsonance of the tautochrone and the

circle would have been particularly pleasing. However, it is clear from

this passage that he shaped his isochronal cheeks by experimenting with

(at least) two weight-driven, seconds indicating clocks. Since the

profile of these cheeks was part of Huygens’ invention, these

experiments must have taken place in

1656. In April 1657, two months before the patent

application, Claude Mylon (1618-1660) expresses in a letter, the wish

that Huygens’ clock will go as well with a spring as it does with

weights, ‘one could wish for nothing more for the longitude.(7

NOT WITH COSTER

So who made these clocks? And indeed who made the clock drawn in

Huygens’ patent application of 14 June 1657, which was approved 2 days

later, after the actual timepiece was inspected by a committee of the

States

General of the United

Netherlands?

It has been assumed that the answer to both questions is Huygens’

assignee Salomon Coster. Before considering why Huygens would have

forsaken his original clockmaker, the evidence against Coster’s

involvement at the experimental stage will be set out.

●

Firstly, a passage that has been cited as pointing to Coster’s priority

is ambiguous and problematic. In Horologium Huygens wrote:(8

...diligent

artificers whom I have informed of the principle of this

invention have been able to add much to it, and they will

discover without difficulty how to apply it to various kinds of

clocks also to those made long ago in the old style. I have

indeed seen in the workshop of him whose labours I first

employed for these constructions, completed clocks which go, not

by weight, but by force of a spring. In this kind of work up to

the present time, the differing power of the spring when wound

up and when wound down was equalised by a fusee, round which was

coiled a gut line; now these are disused. For the teeth are

brought together with the barrel itself in which the spring is

enclosed ....

I pass over clocks of this kind which have been contrived to

sound the hours by one and the same motor, either a weight or a

spring, which serve also for turning the hand of the timepiece,

since all these have nothing to do with my invention except as

occasioned by the opportunity it presents. |

Who, apart from Coster, were these artificers who had been able to do

much to Huygens’ invention? Why use the phrase ‘him whose labours I

first employed’ if, as has always been assumed, Huygens had only one

licensee at the time of writing? Fond as Huygens may have been of the

personal metonym, he could have referred to Coster as he did in his

letter to Pierre Petit of November

1” 1658, as ‘my worker’ or, for example, my

licensee ?

Also, the words, ‘I have indeed seen in the workshop(9

are an unlikely description of Coster’s clocks which he describes in the

opening chapter as, ‘having had many copies ... already for sale and for

sending forth in all directions’. Is it the clocks, made long ago in the

old style, which Huygens had indeed seen, (now converted to pendulum) in

the clockmaker’s workshop? This interpretation better accommodates the

words ‘indeed’ (or ‘truly’, ‘quidem’) and ‘completed clocks’ (‘talia

quoque confecta’). One can imagine the memorable sight of, say, a

horizontal table clock put on its side and converted to pendulum. The

last part of the above passage beginning, ‘now these are disused’ (i.e.

fusee and chains) and describing going and tandem barrel clocks, may

quite properly be interpreted as referring to Coster’s spring clocks.

However, they may not be the clocks ‘seen in the workshop of him’ whom

Huygens first employed. Lastly, the identity of that first employee

depends on a precise identification of ‘these constructions’ which may

refer only to the commercially available clocks and not his experimental

clocks.

●

The circumstances of the patent application may be very significant.

Huygens allowed Coster to present the patent request on his behalf. This

would appear uncharacteristically trusting of Huygens and suggests that

the scientist felt in complete control. It is known that the design was

Huygens’ own and that the Committee of the States General went to

inspect the actual clock before consenting two days later.(10

They subsequently refer to the invention as ‘done by Huygens’

(‘gepractiseert’ by’(11)

with permission for Coster to copy (‘naer te maeken’). This re enforces

the impression that Coster introduced the committee to a clock not made

by him.

●

In summary, no surviving written reference points to Coster as having

been anything other than the sudden and fortunate recipient of Huygens’

commercial assignment.

●

The tangible evidence supports this view. None of the seven surviving

examples of Coster’s work exhibit the slightest rigour of Huyghenian

science. The simple going barrels, hinge swinging movements, inferior

box pillars and cycloidal cheeks are led by the lack of a seconds dial,

in denying any pride in this horological revolution. Admittedly Huygens

considered their design fit for domestic purpose and they justify the

very high antiquarian affection that they currently enjoy. Much

significance has been attached to their dated plaques. It is unusual for

clocks of any period to be dated. However, it is possible that these

plaques were originally tokens, purchased by Coster from Huygens and

representing paid dues on the licence for each clock sold. The plaque

would have been provided with ‘met privilege’ and perhaps the date,

etched in facsimile on them, but otherwise blank for Coster or his

nominee to engrave as they wished.(12

Coster partisans may blame misfortune

for leaving us only examples of his pendulum clocks intended for modest

domestic use. However, there is no indication in Coster’s price list of

work more worthy of the original maker and the appetite of time’s

consumption is not usually so selective.

REASONS FOR CHANGING CLOCKMAKERS

Why would Huygens overlook his original clockmaker when licensing his

patent? There are at least three plausible reasons for so doing.

Firstly, he himself tells us at the beginning of Horologium that he

wished to give his native country,

Holland,

the benefit of his invention. Were that country not the domicile or

nationality of his clockmaker, then eventual disfranchisement would have

been inevitable.

The very fact that Huygens mentions this wish could indicate that there

was an unusual option in a matter, like patriotism itself, normally

taken for granted. Secondly, Huygens’ most treasured possession was his

intellectual property. He may well have thought this would be better

protected by separating development from commercial production. Thirdly,

being in the vanguard of research in the physical sciences, it was

clearly to his advantage to have a more accurate timepiece than anyone

else. He may well have deliberately confined readily available

production to the inferior models of a separate clockmaker. The question

then arises as to whether or not there was an aggrieved clockmaker and

if so, why there are no recorded repercussions. The obvious explanation

is that this clockmaker had little or no creational input, and accepted

from the onset strict conditions of secrecy and the absence of potential

patent rights. Perhaps a notary was involved. However it should also

here be remembered that there is at least one reference to a counter

claim by a clockmaker. Jean Chapelain (1595-1674)

mentions in a letter to Huygens of

20 August 1659, a clockmaker of

Paris,

(‘de notre’), ‘who has tried to rob you of your claim’. The editors of

the Oeuvres Completes conclude that this is probably a reference to

Isaac Thuret (c.1 However they produce no evidence to support this

supposition.(13

mentions in a letter to Huygens of

20 August 1659, a clockmaker of

Paris,

(‘de notre’), ‘who has tried to rob you of your claim’. The editors of

the Oeuvres Completes conclude that this is probably a reference to

Isaac Thuret (c.1 However they produce no evidence to support this

supposition.(13

●

The document that could well settle the mystery of Huygens’ first

clockmaker is the design submitted through Coster to the Committee of

The States General. Sadly, as Drummond Robison(14

lamented 77 years ago,

this has been lost and there are no known copies; or are there?

THE NEGLECTED EVIDENCE

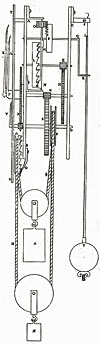

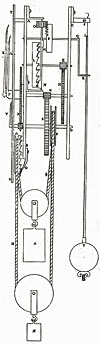

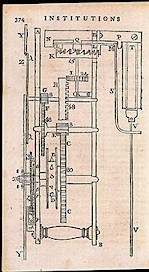

It has long been assumed that the earliest surviving illustration of a

clock by Huygens is that contained in his Horologium of 1658. This

illustration shows his second type of clock, with vertical verge

escapement, ‘O-P’ gearing to narrow the pendulum amplitude, and lack of

isochronal cheeks. This clock beats half-seconds (Fig. 1). The other

published illustration of a conventional pendulum clock by Huygens is

the more famous illustration in Horologium Oscillatorium published 15

years later in 1673.

Fig. 1 (click to enlarge)

Christiaan Huygens’ earliest published

illustration

of a clock, showing his second type of clock

with 0-P

gearing, Horologium, (1658).

(view

high res. picture)

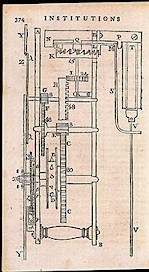

This shows a seconds beating clock with isochronal cheeks and horizontal

escapement Fig. 2. It has been assumed that this is an illustration of a

regulator made for Huygens sometime in the middle or late 1660s.

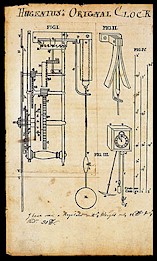

In fact, this is an illustration of Huygens’ first pendulum clock of

1656/7. In all probability it is copied from the original design that

accompanied his patent application. The proof for this is fortunately

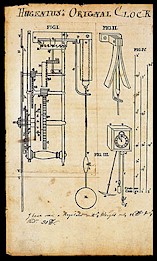

preserved in Benjamin Martin’s (1705-1782) book of 1764, Newtonian

Mathesis(15

original woodcut of 1657 and illustrated it Mathesis) Martin somehow

obtained Huygens’ (Fig. 3) along with the following description:

|

The construction for application of the Pendulum is now somewhat

different from what it was in the original Invention of the

Pendulum Clock by Mr. Christian HUYGENIUS of Zulichem in

Holland

which he first described and published in a diagram cut in Wood

in the Year 1657. And as this may be Justly esteemed as one of

the great Curiosities of Art and was never (that we know of)

exhibited to the view of an English Reader, we shall here

present it, cur in Wood exactly as the Original.

|

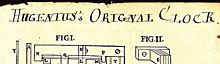

Fig. 2 (click to enlarge)

Horologium Oscillatorium, (1673).

The plate from Benjamin Martin's copy.

(view

high res. picture)

This woodcut is the same side view of the movement illustrated in

Horologium Oscillatorium, though of a different size and without the

pendulum weight or fine adjustment weight. Martin was so taken by this

discovery that he annotated his own copy of Horologium Oscillatorium

with the words, ‘Huygenius’s

Fig. 3 (click to enlarge)

Newtonian Mathesis (1754).

A copy of Huygen's woodcut of 1657

(view

high res. picture)

Original Clock’ above the illustration (Fig. 4).(16

He also reckoned the

date described by Huygens noting, ‘1657 first published his clock’ no

doubt delighted that Huygens’ opening words, ‘Ann us agitur sextus

decimus ex quo fabri cam horologiorum’ tallied with the date of his

woodcut (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4 (click to enlarge)

Benjamin Martin’s annotation above the plate of his copy of Horo/ogium

Oscillalorium.

Fig. 5 (click to enlarge)

Benjamin

Martin’s reckoning of the date on the title page of his copy of

Horologium Oscilatorium.

Since Martin states that the woodcut has never to his knowledge been

seen by an English reader, one wonders whether it was part of the

auction in

Holland

in 1754 of Huygens’ effects. This auction included lenses, a planetarium

and a clock which were purchased by Huygens’ great nephew A.J. Royer,

and left in 1809 to

Leiden

University.(17

●

The fact that Huygens chose to illustrate his first clock in a work

published 16 years later should not come as a surprise to Huyghenian

scholars. It has been known for some time that all but the last part of

Horologium Oscillatorium was drafted by the end of

1659.(18 In

all probability the first chapter was started in October 1659 (although

information on sea trials was appended later). It is obvious that

Huygens would not have commenced his description of the clock without an

annotated diagram. By 1659, with his discovery and proof of the

cycloidal tautochrone, he had discarded his second type of clock with

‘O-P’ gearing (illustrated in Horologium).

There would have been every reason to illustrate his original clock,

probably supplying the diagram of his patent application. The o

improvement on the original clock was an invisible one; the cheeks were

now cycloidal. This was left to the text to explain. There is further

evidence to show that Horologium Oscillatorium used an early diagram

which was later modified.

The theory and shape of the fine adjustment weight which was developed

in the early 1660's

is given a non sequential Greek letter ‘Δ'

indicating that it was not part of the original diagram. The linear

scales from which the theory of this weight was derived, on the far

right (fig. liv in the plate) appear also to be a later addition.(19 Their

description is contained in part 4, written in 1664. It is interesting

to note that Martin’s woodcut does not include this fine adjustment

weight.

Fig. 6 (click to enlarge)

A French engraving of 1671 showing Huygens’ clock which appeared 2 years

later in Horologium Oscillatorium.

There is other evidence that a drawing of Huygens’ first clock

had some circulation before Horologium Oscillatorium. It is included in

a French engraving of 1671 (Fig. 6).(20

A

similar

clock with a great wheel of 96 teeth, is illustrated in a letter Huygens

wrote to Canon Estienne (?- 1723), in 1669.(21

Martin’s description

therefore, must be considered conclusive and the identity of Huygens’

first clock established beyond doubt. Since the thesis of this article

was largely written before discovery of this description, it is not with

the benefit of hindsight to note that the Horologium Oscillatorium

clock shows all the signs of being the prototype.

There are elements which do not flourish in subsequent production; the

boat-shaped pendulum bob, the large diameter escape wheel pinion, the

seconds disc. Being a weight-driven clock beating seconds, it has the

specifications that one would imagine Huygens required to test pendulum

theory. The introduction to the clock and its detailed description in

the text of Horologium Oscillatorium, make more sense as a celebration

of the original movement than the random inclusion of a subsequent

model. Had Huigens wished to be up to date with developments in 1673, he

would presumably have illustrated the anchor escapement.

End

of this section, click

here to continue.

|

Notes: |

|

A |

|

Reprinted from the December 2008 issue

of Antiquarian Horology’.

(back

to text)

|

|

|

1. |

|

M. Nijhoff, Oeuvres Completes de Christiaan Huygens (The Hague,

1932), vol.2, p.l Huygens gives this date for the ‘first model

of that type of clock’ in a letter he sent to Ismail Boulliau

(1605-1694).

(back

to text) |

|

Ismail Boulliau |

|

|

|

2. |

Christiaan Huygens, Horologium (The Hague, 1658), P.4. (back

to text) |

|

3. |

Nijhoff, Op. Cit. vol.2 p. Letter from C.H. to van Schooten, 121

Jan 1657, see also p.7, for letter from Huygens to Mylon, 1”

February 1657. Both letters express the hope that the invention

will be applied to the determination of longitude.

(back

to text) |

|

4. |

The term ‘isochronal’ is here used to describe the purpose and

not the strict qualification. Huygens shaped his cheeks

empirically at this time.

(back

to text) |

|

5. |

Huygens, op. cit. p.1 ‘to me certainly it was not given to

observe anything of this kind ...‘ is Huygens’ comment on

Wendelin’s proposition of variations, (presumably caused, in

part by temperature change) and indicating that he had tested

his invention through the seasons.

(back

to text) |

|

6. |

Nijhoff, op. cit. vol.2, p. (back

to text) |

|

7. |

Nijhoff, O cit. vol.2, p. (back

to text) |

|

8. |

Huygens, O Cit. p.1 (back

to text) |

|

9. |

The word ‘workshop’ is a translation by Ernest L. Edwards, of

the Latin ‘apud’ which is a preposition governing the accusative

case and has a wide range of meaning including ‘at the house

of’, ‘in the works of’, ‘among’, ‘before’, ‘in the presence of’,

etc. It is not certain therefore that Huygens specifically saw

these clocks in a ‘workshop’ for which he could have used the

word ‘officina’. This may become significant with regard to the

location of these clocks seen by Huygens.

(back

to text) |

|

10. |

Nijhoff, op. cit. vol.2, pp. (back

to text) |

|

11. |

The precise definition of the Dutch verb ‘practiseeren’ would

here seem to lie somewhere between ‘carry out’ and ‘use’. It

gives the impression that what the committee saw was ‘done’ by

Huygens and not Coster. A contemporary account of the murder of

William the Silent describes the deed as ‘gepractiseert’ by the

murderer! (back

to text) |

|

12. |

Some plaques have ‘met privilege’ and the date etched or

scratched on them in script different from the Coster signature;

these plaques would appear to be original.

Viz:

Huygens’

Legacy, Hans van den Ende, et. at (Fromanteel Ltd: Isle of Man,

2004), p. (back

to text) |

|

13. |

Nijhoff, Op. Cit. vol.2 p. |

|

14. |

J. Drummond Robertson, ike Evolution of Clockwork (London,

1931), p. (back

to text) |

|

15. |

Benjamin Martin, A New Comprehensive System of Mathematical

Institutions Agreeable to the Present State of Newtonian

Mathesis (London, 1754). Vol. 2. pp.373 For Martin see, JR.

Milburn, Retailer of the Sciences (London, 1986).

(back

to text) |

|

16. |

Christiaan Huygens, Horo/ogium Oscillatorium ... (Paris, 1673).

Sold Christie’s, London, December 2006, Lot 81. Provenance;

Benjamin Martin (double signature on title page, pen drawings,

occasional notes and calculations), John Pope, 1784, (book

plate), John Jackson (pencil signature). (back

to text) |

|

17. |

C.A. Crommelin, Descriptive Catalogue of the Huygens Collection

.. (Leiden, 1949), PP. |

|

18. |

Joella

C. Yoder, Unrolling Time (Cambridge, 1988), p.5. (back

to text) |

|

19. |

It is clear that a smaller script has been used in fig. IV of

Plate One of Horologium Oscillatorium. (back

to text) |

|

20. |

A.E. Bell, Christiaan Huygens and the Development of Science in

the 17th.

Century

(London, 1947), Plate 3. (back

to text) |

|

21. |

Nijhoff op. cit. vol.6 pp. (back

to text) |

|

22. |

Johan Lulofs, Waarneeming van Mercurius op de schyf der

Zon, den 6Mey 1753, gedaan Ce Leyden (Haarlem, 1754), pp.37

(back

to text) |

|

23. |

R.H. van Gent & J.H. Leopold, Timekeepers of Leiden

Observatory

(Leiden, 1992), p. note 37. (back

to text) |

|

24. |

Reinier Plomp, ‘A pendulum Clock Owned by The Danish Astronomer

Ole Rømer (1644-1710)’ Antiquarian Horology 30/5 (March 2008),

624-628. (back

to text) |

|

25. |

They have been checked with their TPI and, as to be expected, do

not conform to any standard threads. They have nor yet been

compared to the threads or diameters of the Boerhaave clock.

(back

to text) |

|

26. |

J-D. Augarde, Les Ouvriers do Temps (Geneva,

1996), p.

(back

to text) |

| 27. |

Nijhoff, op. cit. vol. 1V, p.llO.

(back

to text) |

|

28. |

Nijhoff, op. cit. vol.V, p.383.

Also RH. van Gent & J.H. Leopold, op. cit. p.l3. (back

to text) |

|

29. |

Reinier Plomp, ‘A longitude timekeeper by Isaac Thuret .with the

Balance Spring Invented by Christiaan Huygens’ Annals of

Science’ 56 (1999), (back

to text) |

|

30. |

Yoder, op. cit. p

(back

to text) |

back

|

|

By:

Sebastian Whitestone

&

Jean Claude Sabrier. |

Reprinted from the December 2008 issue

of Antiquarian Horology’. |

Back to end of previous section.

Back to end of previous section.

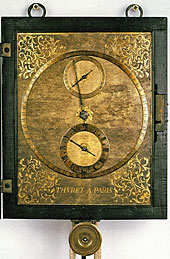

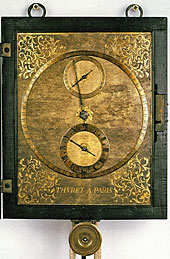

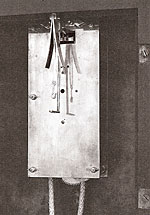

TWO SURVIVING EXAMPLES

Martin’s copy of Huygens’s woodcut, (and of course the plate in

Horologium Oscillatorium), show a movement known only in the work of

Isaac Thuret. There are at least two examples of this exact movement.

One is a hitherto unpublished example discovered 30 years ago by

Jean-Claude Sabrier. The other example is now in the

Boerhaave

Museum,

Leiden

(Figs 7 & 8) and is held by long tradition to have been the personal

property of Christiaan Huygens. In 1754 Johan Lulofs (1711-1768) wrote

of his observations at Leiden, ‘the timepiece that I used was made in

Paris by Thuret under the supervision of Mr. Huigens... ‘.(22

Leopold and van Gent(23

believe this clock was one of two first mentioned in an inventory of the

Observatory in 1706.

If so, then the clock left to

Leiden

University

by the Royer bequest in 1809, is another clock. The gearing in the

Leiden

clock is identical with Huygens’ diagrams apart from the 40/20 contrate

to escape wheel pinion instead of 48/24. There is, according to Plomp,

another similar Thuret clock in a private collection. There is also a

clock with similar train but with only two pillars in the Ole Rømer

Museum, Denmark. This clock is unsigned and may be a later Danish copy

of the Boerhaave clock.(24

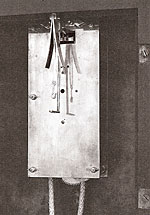

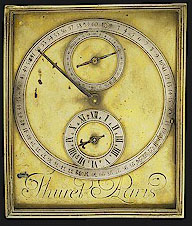

Fig. 7 (click to enlarge)

The clock by Isaac Thuret, Museum Boerhaave,

Leiden,

inv.no.Vg854.

Fig. 8 (click to enlarge)

The back plate of clock by Isaac Thuret, Museum

Boerhaave,

Leiden,

inv.no.Vg854.

●

Thirty years ago Jean-Claude Sabrier was asked while visiting a French

Chateau, to examine a clock kept in a cardboard box in the attic.

He informed the owners of the great importance of this clock and

persuaded them not to restore it. A few months ago, in preparation for

this article, he persuaded the current owners to release the clock for

thorough examination and restoration and full details of it follow in

Figs 9-23.

Fig. 9 (click to enlarge)

The Thuret clock discovered by Jean-Claude Sabrier, the case with

opening door.

(view high res

picture)

●

The case is made of brass with hinged and glazed front door and sliding

back panel. It is attached to the dial by four screws inserted in

right-angle brackets attached to the back of the dial. The case is hung

on the wall by rings at the side and not on the top. Large pyramidal

headed screws adjust the distance from the wall. The dimensions are: 175

x 132 x

108 mm.

●

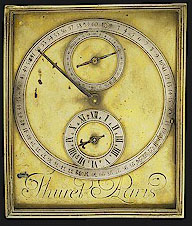

The dial is gilded brass with silvered chapter rings and original steel

hands. The chapter rings are now screwed to the dial plate. The

signature has two small unused holes at either end

suggesting a covering plaque. The dimensions are: 235 x

192 mm.

●

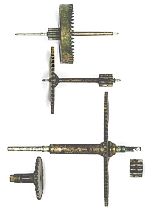

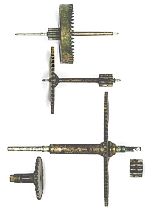

The movement has exactly the same train as in Huygens’ diagram (see Fig.

2). The train count corresponds to a 1 second pendulum.

| Train |

|

| 80 |

First wheel |

|

8 |

48 |

Intermediate wheel |

| |

8 |

48 |

Contrate wheel |

|

|

24 |

15 |

Escape wheel |

|

|

Pendulum |

|

Beats 60 p/m

Nominal length 1 m.

(1 sec.)

|

Fig. 10 (click to enlarge)

Original hands.

(view high res.

picture)

Fig. 11 (click to enlarge)

of the metal box case and dial.

(view high res.

picture)

Fig. 12 (click to enlarge)

Thuret clock, side view, metal box case,

hanging loops riveted to case

sides.

(view

high res. picture)

Fig. 13 (click to enlarge)

Thuret clock, back view, box case removed.

(view high res.

picture)

Fig. 14 (click to enlarge)

Thuret clock, back of dial, case and movement removed.

(view high res.

picture)

Fig. 15 (click to enlarge)

View of movement, note the crown wheel and large diameter pinion. Also

note the hole in the first arbor originally used for the pin securing

the driving pulley

(now missing)

(view high res.

picture)

●

The dimensions of the movement plates are:

back 148.5 x

77 mm, front 167.5 x

77 mm. The first-wheel arbor was originally fitted

with a driving pulley. Assuming the dimensions of the movement plates in

the drawing of Fig. 2 are the same as this clock then one can determine

that the diameter of the pulley was about

25 mm.

This diameter would give a drop of

188 cm

per 24 hours. The height of the clock centre for 30 hours would be at

least

235 cm or

7 ft

10 in.

Fig. 16 (click to enlarge)

The outer sides of the back (left) and front (right) movement plates.

(view high res.

picture)

Fig. 17 (click to enlarge)

The inner sides of the back (left)

and front (right) movement plates.

(view high res.

picture)

Fig. 18 (click to enlarge)

Thuret clock. The wheels and pinions.

(view high res.

picture)

Fig. 19

(view high res.

picture

●

To increase the duration between windings and allow for a lower

positioning on the wall this pulley has subsequently been removed and

the first wheel arbor extended through the back plate for an additional

pinion. This pinion was driven by an extra wheel (now missing) situated

between the bracket and the backplane, its arbor pivoted at the front in

a small cock secured to the inside of the front plate. The arbor of this

extra wheel carried the new, and probably larger, driving pulley. The

lower position of this pulley was only accommodated by filing flats on

the insides of the two lower pillars. The ratchet

pulley mounted on the back of the dial may still be the original, but

reversed.

Fig. 20 (click to enlarge)

The back-cock would have originally held a silk suspension (two threads)

and the cycloidal cheeks.

(view high res.

picture)

There is a section of partly threaded square brass rod which was found

with the clock and has been recorded in case it was part of the original

pendulum. It is too large to pass through the pendulum crutch however it

may have been part of a lower section of the pendulum. The pulleys,

weights and pendulum

are missing.

Fig. 21 (click to enlarge)

Pyramidal headed screws for adjusting

the vertical position of the clock

on the wall.

(view high res.

picture)

|

TPI25 |

fig. |

Screw thread. |

| 48 |

|

Wheel

bracket.

|

| 32 |

|

Bottom

potence. |

| 32 |

22 |

Back

cock. |

| 32 |

|

Minute

bridge. |

| 32 |

23 |

Case.

(brass) |

| 20,5 |

21 |

Case

back plate. |

| 23 |

|

Pendulum

rod. (brass) |

Table 2

screw thread details.

Traditional Inch/Pouce = 27.07 mm.

Fig. 22 (click to enlarge)

Back-cock screws.

(view high res.

picture)

Fig. 23 (click to enlarge)

Case

securing screws.

(view high res.

picture)

●

The two screw holes in the dial plate either side of the signature are

interesting. The only explanation for these holes is that they once held

a plate covering the signature. The hiding of Thuret’s name would very

much resonate with Huygens’ secretive behaviour. It is quite possible

therefore that both clocks belonged to Huygens and there is no reason to

believe that they are not of the same date as the 1657 woodcut.

●

With regard to their description in previous articles as astronomical

regulators it is important to remember that any experimental clock of

this period that was designed to be tested accurately would be regulated

with reference to astronomical observation and therefore likely to have

regulator dials.

ISAAC THURET

Isaac Thuret was born into a Protestant family at Senlis in

France,

around 1630. He acquired impressive social connections. His sister

Susanne married Charles Francois de Sylvestre, Maître de dessin des

Enfants de France and his son Jacques married the daughter of the famous

designer to the court of Louis XIV, Jean Bérain.(26

A 25 year- old Thuret, rapidly becoming

France’s

greatest seventeenth century clockmaker, would have been a natural

contact for his contemporary Huygens, when the latter visited

Paris

in 1655. Huygens spent 4 to 5 months in

France

in the autumn of that year, mainly in

Paris.

There is no mention of Thuret’s name in Huygens’ correspondence

published in the Oeuvres Completes until 1662 when the latter is

informed that his father was impressed by Thuret’s clocks and asks his

brother Lodewijk, in a letter of April l2 ‘how are these Thuret clocks

made, for which my father pays 10 or 12 pistoles and prefers to his own?

If we could know the form it could be used to instruct the clockmakers

here...'.(27 This reference has been taken as indicating Huygens’ lack of

acquaintance with Thuret, sometimes giving the impression that it is a

general enquiry about Thuret’s work. However the complete passage

clearly shows that it is an enquiry about a specific type of clock with

which Huygens’ compatriots, under his patronage, were in direct

competition. Huygens is responding here to a previous comment and taking

advantage of his brother’s location in

Paris.

Given also Huygens’ conflict of interest, the request in this letter is

not surprising and does not preclude previous close cooperation between

Thuret and himself.

●

The next reference to Thuret, again in family correspondence, occurs

several times in 1664 and concerns the sending of clocks made by Claude

Pascal to Thuret for repair.

Jean Chapelain

(1595-1674)

In 1665, Jean Chapelain writes to Huygens

on the subject of the latter’s remontoire clock for which a French

patent was granted, ‘that excellent clockmaker Monsieur Thuret, of whom

you yourself have told me much good, visited me yesterday and asked me

to offer you his services for the construction of clocks to be used on

ships and for their sale and distribution.. ‘.(28

Chapelaine was authorised

to dispose of the patent on the inventor’s behalf and it was probably

that fact, or the chance that a random visit presented, that caused

Thuret to make this indirect approach. Huygens agreed to this request 2

weeks later.

●

In 1666 Huygens moved to

Paris

and presumably continued to employ Thuret. However the next episode

involving the two that appears in Oeuvres Completes is their

collaboration and subsequent contention over the balance spring which

took place in 1675 and is outside the scope of this article

CONCLUSION

The clock illustrated in Horologium Oscillatorium has up to now

been attributed without dispute to Isaac Thuret(29

albeit without realising its early date. There is no need to withdraw

this attribution. To the contrary, Huygens had ample opportunity to meet

Thuret in

Paris

in the autumn of 1655. Huygens himself is linked to one of the surviving

Thuret clocks and both examples described here, certainly look as early,

if not earlier than the Coster clocks. For the sake of completeness it

may be asked whether Thuret clocks could be later copied from this

illustration rather than visa-versa. However, the clock in the

illustration, like Huygens’ research in early 1657 reveal the work of a

clockmaker, and the search for someone else would be at the expense of

plausibility. It is probable that Thuret did not initially have

permission to make these clocks for anyone other then Huygens and by

the time that restriction had ceased, clock design had progressed beyond

the need to reproduce the original model.

●

The remaining problem concerns the fact that the first mention of

Thuret’s name in the Oeuvres Completes is 7 years after Huygens’ first

visit to

Paris.

The likelihood is that Huygens went to great lengths to keep Thuret and

his contribution secret. However, it is also very important here to

recognise the limits of the Oeuvres Completes in general and Huygens’

surviving correspondence in particular. This is a classic example of

where absence of evidence is not, of itself, evidence of absence. As is

so often the case, it is not known how Huygens compiled or subsequently

edited his own correspondence. It is far from complete. Where is the

trade correspondence? Did he later remove contentious or awkward

material with a view to posterity?

●

Apart from his alleged secrecy there is an aspect of Huygens’ character

which is relevant to the changing dynamic of his relationship both with

his invention and with Thuret; and that is the rapidity with which he

progressed through successive projects.

●

This progression should be viewed against the backdrop of his

many simultaneous scientific enquiries. Naturally his first horological

priority was to eliminate variation and this meant, among other things,

that he had to start with weight drive. By early 1657, while preparing

to franchise various imprecise domestic models, he was working, almost

certainly in secrecy, on a maritime pendulum clock with spring drive as

mentioned in the Mylon letter quoted previously. Huygens was clearly

confident of overcoming the problems of pendulums at sea. For ships’

chronometers he favoured a going barrel without fusee. Although he

vaunted the resistance of his isochronal pendulum against the variations

of power in a going barrel, the main reason for rejecting the fusee was

its lack of maintaining power during winding. However, he found that his

isochronal cheeks, fine when stable in a wall clock, changed the

pendulum length when even slightly tilted. This led him, in late 1657 or

early in 1658 to develop his half-second clock with ‘O-P’ gearing. This

gearing avoided the need for isochronal cheeks

by lessening the amplitude of the pendulum to that arc where the

circular and the tautochrone hardly diverge. This second clock was

therefore presumably intended to be developed into a marine clock

although the possibility of an increase in pendulum amplitude caused by

pitch or roll must have been a concern. Again Huygens commenced by

testing a weight driven version and he presumably found that the

performance was insufficient for further development in marine use. At

this point he probably realised that longitude horology required a

radically new approach.

●

In November 1659, Huygens developed a conical pendulum clock

( ) which he

used to obtain a new value for the constant of gravitational

acceleration. It is not known who constructed any of these subsequent

clocks. It is established that his conical pendulum clock existed, for

he obtained his new value for free fall, ‘ex motu conico penduli’

(30

The

lack of any mention of it in the correspondence of the Oeuvres Completes

and the editorial speculation that it did not exist, provides a further

caveat to regarding such an archive as an audit of events. With his

extraordinarily busy life and changing agenda, it is quite possible that

Huygens temporarily abandoned his far-off Parisian clockmaker in the

first years of the 1660s, if not before. The lack of mention of Thuret

in Huygens’ papers is no doubt chiefly due to the fact that Huygens saw

no share for the constructor in the celebrity of his invention. At least

two Thuret clocks have thus been deprived for 350 years of their proper

recognition. They are the sisters of his first pendulum clock and the

earliest surviving models of the first complete pendulum theory. And as

such they embody what may be, despite modern perspective, the defining

achievement of a prolific immortal of the Scientific Revolution. ) which he

used to obtain a new value for the constant of gravitational

acceleration. It is not known who constructed any of these subsequent

clocks. It is established that his conical pendulum clock existed, for

he obtained his new value for free fall, ‘ex motu conico penduli’

(30

The

lack of any mention of it in the correspondence of the Oeuvres Completes

and the editorial speculation that it did not exist, provides a further

caveat to regarding such an archive as an audit of events. With his

extraordinarily busy life and changing agenda, it is quite possible that

Huygens temporarily abandoned his far-off Parisian clockmaker in the

first years of the 1660s, if not before. The lack of mention of Thuret

in Huygens’ papers is no doubt chiefly due to the fact that Huygens saw

no share for the constructor in the celebrity of his invention. At least

two Thuret clocks have thus been deprived for 350 years of their proper

recognition. They are the sisters of his first pendulum clock and the

earliest surviving models of the first complete pendulum theory. And as

such they embody what may be, despite modern perspective, the defining

achievement of a prolific immortal of the Scientific Revolution.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to express my gratitude to Jean-Claude Sabrier for

discovering and making available a hitherto unpublished Thuret clock.

And to Andrew Crisford who provided from his libraries the conclusive

evidence of Benjamin Martin.

March

2009, Copyright:

LINKS

Chr.

Huygens Horologium 1658.

(pdf)

The

Antiquarian Horological Society.

(This article is subject to ongoing

revisions.) |