|

Tompion bracket

|

Knibb bracket

|

Knibb longcase

|

Tompion di Medici

|

Tompion

year clock|

A comparison

of the lives and work of

THOMAS

TOMPION

and

JOSEPH

KNIBB

As a dealer in Antique Clocks, more specifically in English domestic clocks, my interest has been, for many years, in the clocks that were made in London, particularly those made by clockmakers whose work influenced others. The consequence of this has been my good fortune to have had some of the finest

English clocks ever made, pass through my hands. Some of these, along with others, I intend to discuss in this lecture.

We are all aware that an antique clock is technically a mechanism recording the passing of time, but today I refer to a clock as a mechanism encased in a cabinet. It was the clockmaker who was the greatest influence on the design and construction of the case, with the object of bringing the clock and case together to make an item of both technical and aesthetic excellence.

I don't pretend to be a technician or an academic. Much of the basis of my knowledge has been acquired from the experience of handling these clocks and I am forever grateful for the support of the clockmakers and cabinetmakers who have assisted me.

There could be no more appropriate a place to hold a lecture involving the work of Joseph Knibb than in the city where he established his first business in Holywell Street, only a few hundred yards from where we are today. My lecture concerns the work of Joseph and his contemporary Thomas Tompion. These two

eminent makers had an enormous influence on the development of clock making in England during the seventeenth century and, interestingly, there were many parallels in their lives. In view of the fact that Joseph Knibb returned to Oxford towards the end of the seventeenth century I will conclude my comparison at the end of the William and Mary period.

Both men were born in the provinces, Thomas in 1639 close to Bedford and Joseph only a few months later in Claydon. Joseph was one of a famous family of clockmakers. Samuel, Joseph's cousin, established his business in Newport Pagnell and it was there that Joseph, together with his younger brother John, served his apprenticeship to his cousin. Around 1662 Joseph set up a workshop in Oxford and two years later in 1664

was joined by his cousin, John, as an apprentice. A fourth, though lesser known member of the Knibb family, a cousin called Peter, was apprenticed to Joseph in 1668.

At the age of thirty in 1670 Joseph left Oxford for London and the same year became free of the Clockmakers' Company. The name Knibb was already well established in London. Samuel, Joseph's cousin, had left Newport Pagnall some seven years earlier and was well known in London as a fine craftsman. In fact he had

been recognised by King Charles II, who had requisitioned two clocks for Windsor Castle. It is unlikely to have been a coincidence that history tells us that Joseph arrived in London in 1670 and that in the same year Samuel died at the young age of forty-five - who knows what he would have accomplished had he lived longer. It is an assumption that Joseph travelled to London to

take over his cousin's business which had been established in Westminster. Joseph started the new workshop under his own name at the sign of `The Dial' in Fleet Street.

Thomas Tompion was born in Northill, Bedford, only thirty-five miles from Joseph's birthplace. His father of the same name was known to be a blacksmith. Remarkably little is known of how Thomas learnt his trade but it is believed he moved to London in 1671, becoming a Brother of the Clockmakers' Company. In 1674

he purchased his workshop for the sum of £80 on the corner of Water Lane and Fleet Street. His sign of `The Dial and Three Crowns' hung in Fleet Street. It is fascinating to consider that the two most influential clockmakers in the last quarter of the seventeenth century, born within months of each other and only thirty-five miles apart, had now set up business not only in the

same city, but in the same street, little more than 350 yards apart.

Following the Great Fire, Fleet Street being a main thoroughfare was nominated as a `Principal Street'. It would have been a busy street, considerably wider than the lanes that ran from the street down to the river Thames. The houses which flanked the street would have been constructed primarily of brick, being three or four storeys in height, generally with a garret. Many

would have been private residences whilst others would have had a tradesman's shop at ground floor level. The street itself would have been cobbled with an occasional post marking the pavement from the road where coaches and carts ran in abundance. The toffs would have been carried in a sedan chair or would have travelled in a coach so avoiding the decaying waste and rubbish

lining the streets. There was no street lighting at this time and the streets in darkness were extremely unsafe. Robbery was a hanging offence and it was not unusual for muggers to murder their victims, thereby eliminating the risk of later recognition. Petty crime was also rife - it was commonplace for servants whose wages were a paltry few pence a week, to steal from their

employers to supplement their income, not necessarily cash, but more often supplies such as tea, alcohol and provisions, all of which had to be kept under lock & key. Even the clocks had to be

kept securely locked and were wound and adjusted by the master to prevent the staff

tampering with the time to deceive their employer about their late arrival to work.

During the early years Joseph, was greatly influenced by the work of Fromanteel, but by his mid-thirties he had developed a style of his own, showing flair and becoming increasingly innovative. It is thought by many than he invented the tic-tac escapement and also that he introduced the fascinating Roman striking mechanism. His great flair extended to the design of his clock

cases, which developed a petite, elegant and restrained style. Not only was Joseph making longcases and table clocks, but also night clocks and many wall hanging clocks in the form of lantern and hooded clocks.

In his excellent book, The Knibb Family, Ronald Lee identified the four phases of Joseph Knibb's development. Phase 1 commenced with his work in Oxford and continued to his earliest years in London. Phase 2 clocks are considered to be those made from the early 1670s through to about 1680. In my view, this phase contains his finest work and the pinnacle of his achievement. The

third phase, from 1680 through to about 1690, was the time that his clocks took their most elegant and restrained style.

In his fourth phase, perhaps indicative of the gradual decline of the business, he appears to have bowed to fashion with many of his clocks, following the style of other makers who had established themselves during the 1690s. In 1697, after selling his remaining stock through an advertisement in the London Gazette, Joseph moved to Hanslop where he continued to make a few clocks

until his death in 1711.

Tompion's life in London took a different path. Whilst his early clocks bore great resemblance to those of Knibb, indicating collaboration between the two, there was a significant turn in his career early in 1674, when he fortuitously established a friendship with Dr Robert Hooke, Curator of Experiments for the Royal Society.

Hooke introduced Tompion to the astronomer John Flamsteed and the eminent mathematician, Sir Jonas Moore. With the help of Hooke, Thomas applied a particular balance spring to a watch, the first English maker to do so, and with such success that his watches were in high demand, even beyond the shores of England. Hooke ordered a watch from Tompion which was of such quality and finesse, that Hooke showed it to the King. Charles was equally impressed and asked Tompion to make a similar one for him, the first of many watches and clocks made for the King. All this took place in 1674-5, arguably the most important years of Tompion's life because, apart from his apparent skills, these contracts were to form the basis of Tompion's future reputation. A short time later Christopher Wren, then the most important architect in London, was commissioned to design the Royal Observatory in Greenwich. On completion of the Observatory, Flamsteed was appointed Astronomer Royal. Sir Jonas Moore ordered two clocks from Tompion and gave them as gifts to Flamsteed to be installed in the Observatory.

Tompion's business was now firmly established and supported by the Royal patronage, his clients included the aristocracy and wealthy merchants of the times. His style of design was subtly different from that of Joseph's. His movements were more robust and he introduced to his table clocks a most complex but wonderful quarter

repeating mechanism.

Around 1680 he started a numbering series to his clocks. In many instances both movement and case were numerically stamped. He was the first maker to do this and it has greatly helped in placing his clocks in some form of chronological order. By and large at this time his clocks, like Joseph's, were elegant and restrained but by the last decade of the seventeenth century his

clocks began to take on a more flamboyant design. Charles 11 had been a great patron of Tompion but this royal patronage was surpassed by the enthusiasm of William III. William, together with his wife Mary, enjoyed a more flamboyant style to their furnishings and they employed a Huguenot designer, Daniel Marot, who had been trained in the French royal workshops and who was to

influence the design of several important clock cases.

Tompion collaborated with Marot to produce a number of royal clocks, some for the personal use of the King and Queen and several they requisitioned as gifts to their royal counterparts in Europe and as far field as Tunisia.

Following William's death Tompion was fortunate to acquire yet another enthusiastic royal patron, Queen Mary's new husband, Prince George of Denmark,

Duke of Cumberland, for whom Tompion made several clocks.

In 1702 Queen Anne came to the throne. Sadly, she did not share the name passion and enthusiasm as her predecessors for

Tompion's work and, without the royal patronage, Tompion returned to a more restrained and dignified style of work.

His clock cases were designed with greater sobriety, they maintained a special dignity and with the aid

of his partner for a short period, Edward Banger, followed by George Graham, the quality of his workmanship was unsurpassed.

Summarising, I have looked at the lives and work of two of the greatest craftsmen this country has ever produced. Young men from humble backgrounds who went to London to seek their fortunes. Both creative individuals, developing their own distinctive styles of work and cabinet design.

Tompion started a dynasty. On his death in 1713 and his burial in Westminster Abbey, he was succeeded by his then partner and nephew-in-law, George Graham, who carried on his fine work. On Graham's demise his apprentices Thomas Mudge, William Dutton, Sam Barclay and Edward Colley continued the line, followed by Dutton's sons, Thomas and Matthew. Had Knibb formed an association

similar to that formed by Tompion with Robert Hooke things may well have turned out very differently, but nonetheless the abilities of both were recognised by royalty, the aristocracy and the wealthy traders of their day and far beyond the capital.

From the examples described and illustrated I have shown my reasons for believing that for some period of time, these two great craftsmen must have collaborated and exchanged ideas, living and working as they did within a stone's throw of each other.

It is even possible that the outstanding contributions to horology of these two icons of the seventeenth century resulted to some extent from a little healthy competition between them.

Anthony Woodburn,

Oxford 16 April 2000

Type: 'Ctrl+F' to find any word on this page

|

|

|

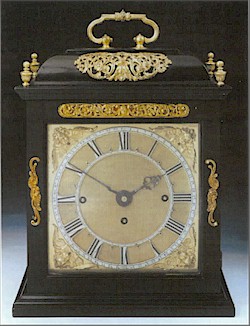

| Knibb bracket | |

|

|

|

|

An illustration of a very fine phase III Knibb bracket clock

. Whilst it is similar in size to phase II clocks, several subtle changes have taken place. The shape of the handle has changed as has the domed basket top and its gilt mounts. As with the phase II case there arc no feet to the base. One occasionally sees feet on the base of these clocks but generally they have been added at a later date. The clock has three train movement

with grande sonnerie striking, the quarters being sounded on three bells.

|

|

|

|

|

|

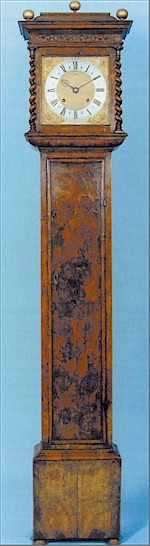

For some forty years from 1670 onwards trunk doors in London clocks measured 42 or 43 in., as a general rule.

|

|

|

tompion year clock

|

|

|

|

|

|

This Year Clock

, is believed to have been commissioned in1689, the year of the coronation of William and Mary. It bears their coat of arms. The gilt brass dial has silver mounts and the minute hand is counterpoised. The clock is signed on a silver cartouche just above VI. It has a spring driven movement with pulls to repeat the quarters (from either side), rack and mail striking and short

verge pendulum. It may well be that the King did not receive the clock until 1693 and, if so, during that year it is recorded that Tompion was paid

the sum of £600 for a fine clock. This may have been the clock in question. It was a vast sum, particularly when compared to a worker's wage which would rarely exceed a shilling a week. Daniel Marot was paid £50 at the name time, again a princely sum. Photograph by permission of the Trustees of the British Museum. |

|

|

|

|

|

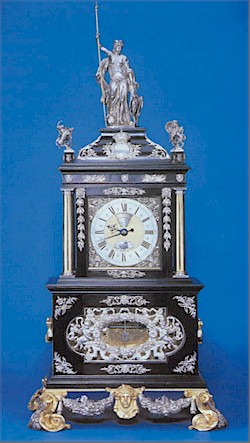

This clock, known as the Medici

, Tompion, numbered 278

was supplied to King William in 1698 and given to Cosimo III de Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. It is a grande sonnerie striking clock, the quarters sounded on six bells, and the layout of the dial is typical of Tompion's work for the fifteen years to follow. It is another of Tompion's wonderfully flamboyant clocks made for King William as a presentation clock, at the end

of Tompion's golden period, when he was the master clockmaker in Europe. To impress his counterparts with British craftsmanship, King William took great pride in purchasing clocks from Tompion as gifts for eminent Europeans.

|

|