|

THE INVENTION OF THE

PENDULUM CLOCK

PART 1/5

The real story

(Type

Ctrl+F

to find any text on this page)

PREFACE

PREFACE

One of the best documented inventions in history

is the invention of the pendulum clock. At the same time it is one of the

most disputed ones, especially so from the English side. For some reason

this invention is of such importance that continuously claims are launched

to appropriate it. We will represent here the real course of events, based

on facts, scientifically accepted sources, archival documents, circumstances

and events during the time of the invention.

The immediate reason to do this now is the magnificent and overwhelming

exhibition

‘Innovation

& Collaboration

The early development of the pendulum clock

in London’

held at Bonhams in London between 3 and 14 September 2018; and

particularly the catalogue published on the occasion of the exhibition.

Where the exhibition exceeded all imagination on visualising early clock

making in England, the catalogue falls short of any sense of reality.

An

actual falsification of history is presented, based on half-truths,

interpretations, speculations, suggestions and simply untruths.

Four quotes form the basis of our criticism and

illustrate the above allegations: Four quotes form the basis of our criticism and

illustrate the above allegations:

“And if

credibility is given to the revised succession of events advanced at this

exhibition, namely that Fromanteel was working on pendulum deployment with

Christiaan Huygens from at least 1656, then by the time of the pendulum's

commercial launch in autumn 1658, marked by the distribution of Huygens's

Horologium in September (Cat.

25) and Fromanteel's advertisement in October, Fromanteel would have passed

the development stage and would have worked through a number of stages of

movement design and layout.”

(2

“A central

revisionary tenet of this exhibition, namely that John Fromanteel,

notwithstanding that he was technically still an apprentice, arrived at

Coster’s in The Hague in September 1657 to teach (rather than be taught by)

the Dutchman the mysteries of pendulum clock making, …”

(3

“Under the

new interpretation advanced in this exhibition, in which Huygens the

inventor employed Ahasuerus Fromanteel, as the practical technician, to

develop, construct, and perfect working models incorporating the Dutchman’s

pendulum invention for the domestic market (as opposed to scientific

market), it would seem expected, rather than merely coincidental, that the

cases of the earliest pendulum clocks made in London and The Hague were so

similar.”

(4

There are

many unfounded and unverified theories published in the last decades, but,

as Christiaan Huygens himself wrote to the Lords of the States of The

Netherlands when publishing Horologium in 1658:

“It is

certain that elsewhere also will arise men, who will envy our little fame

and perhaps try to convince themselves, but certainly the whole world,

that this invention is not due to

the acuteness of our compatriots, but rather long before was brought to

light by the zeal of themselves or one of their own”

(5.

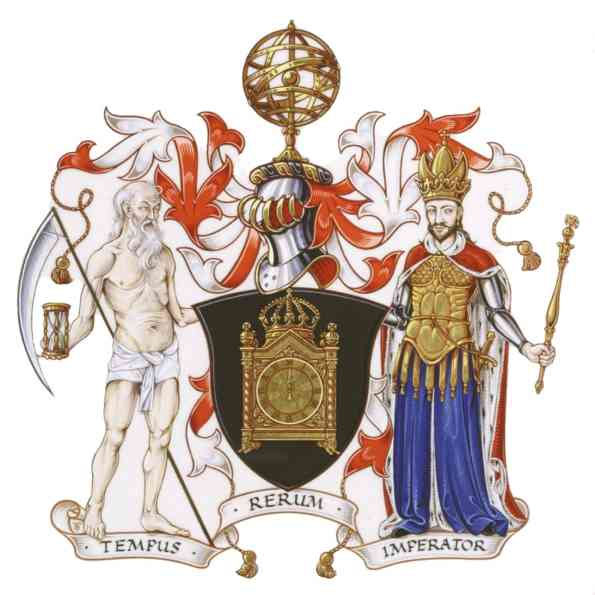

In this article we will set out the real story of

the invention of the pendulum clock, based on all currently known sources.

We will do this by discussing the main

characters: Christiaan Huygens as inventor, Ahasuerus Fromanteel I, the

maker of the first pendulum clocks in England; his eldest son John

Fromanteel; Salomon Coster, maker of the very first pendulum clock; the

‘Contract’ between Salomon Coster and John Fromanteel. And also by

reproducing the historical context and developments, situations, sources,

artifacts, clocks and how it all fits together.

All data will be discussed in chronological order

as much as possible, but sometimes we have to jump back- or forward because

of simultaneous developments in Holland or England. Obviously the playing

field of the invention of the pendulum clock is much wider than discussed

here, especially in relation to the developments between Holland and France

and in France itself, but this part of the story is omitted here on purpose.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

The start of the 80 year war

between Spain and The Northern Dutch Provinces and especially the

capture of Antwerp in 1585 by the Spanish troops, caused a stream of

protestant ‘Flemish’ refugees to the north, but also a large group

crossed over to England. Among them were the ancestors of Ahasuerus

Fromanteel, who was born in Norwich in 1607

(6.

In 1631 Ahasuerus joins the Blacksmiths’ Company, and in 1632 he

becomes ‘Free brother’ with the newly founded Worshipful Company of

Clockmakers. (7

He seems to have set up a flourishing

workshop as instrument maker and lens grinder;

he

also produced clocks

commissioned by other

makers.

(8

We do not know exactly when Salomon Coster is born.

Coster was a Mennonite, so there is no birth certificate. Several

sources mention a date of 1622, which is an accepted guess by

subtracting 21 years

(9

from his

marriage date: Coster married Jannetje Harmens on March the 22nd,

1643

(10.

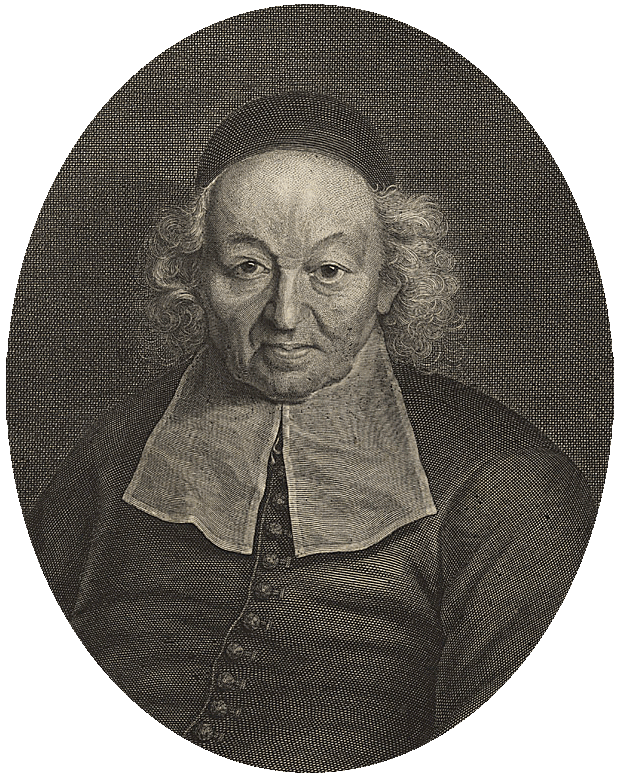

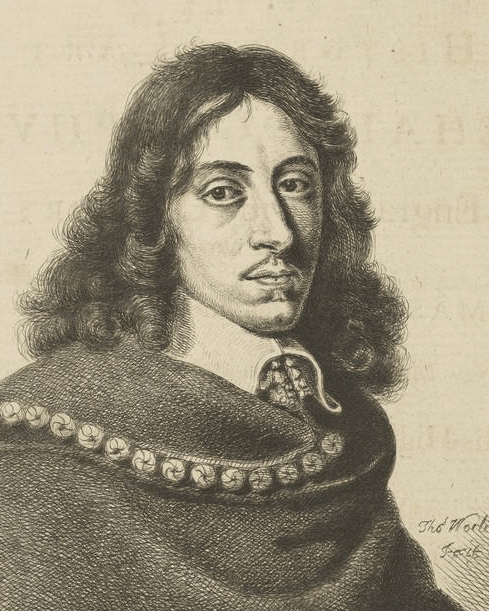

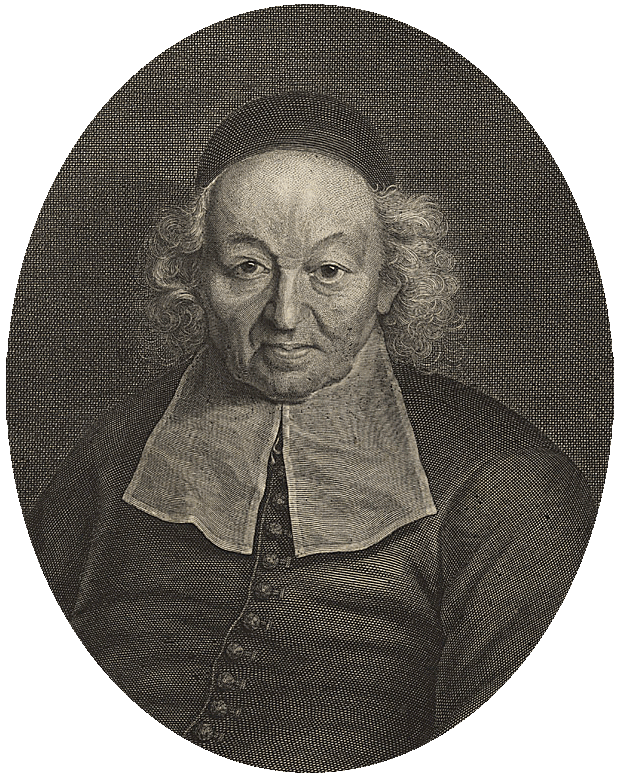

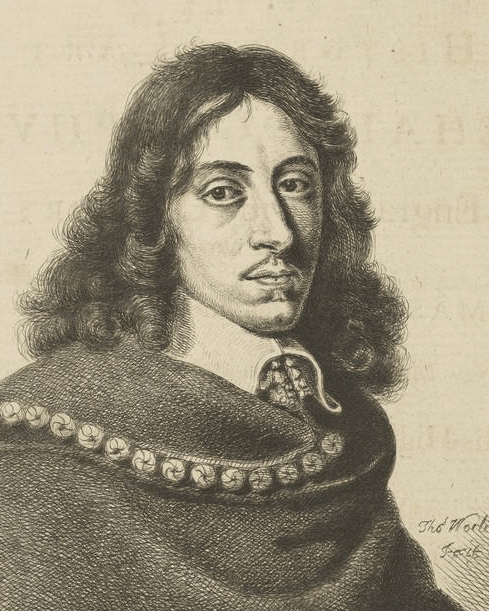

Christiaan Huygens 1629-1695

Christiaan Huygens was born 14 April 1629, in

a prosperous and distinguished family living in The Hague. His

father, Constantijn Huygens (1596-1678), was a diplomat, secretary

to the Princes of Orange, and also a poet and a composer. Christiaan

had one older brother, Constantijn jr., two younger brothers and a

younger sister.

Christiaan studied law and mathematics at

Leiden University from 1645 to 1647, amongst others with the

stimulating mathematician Frans van Schooten, with whom he would

continue to correspond intensively until the death of the latter in

1660. After his time in Leiden Christiaan and his younger brother

Lodewijk continued their education at the ‘Breda College of Orange’,

the Illustrious school and Collegium Auriacum, where his father was a

curator(I.

As early as in 1649 Huygens

publishes his first scientific work on hydrostatics. In the following

years Huygens focuses on multiple mathematical issues (calculation of

the length of curves and quadrature (area) of hyperboles, ellipses and

circles), physical issues and astronomy (Jupiter's Moons, Saturn's

Rings).

(11

Johannes (John) Fromanteel is born ca. 1638 and first becomes

apprenticed by his father.

The notes of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers

of 5 April 1652 indicate, that

‘John

Fromanteel before the Court is bound to Ahasuerus Fromanteel as

apprentice’. On 5 April 1659 ‘John

Fromanteel becomes journeyman’ and on 6 July 1663 ‘John

is freed and becomes Freeman’.

(12

CORRESPONDENCE

CORRESPONDENCE

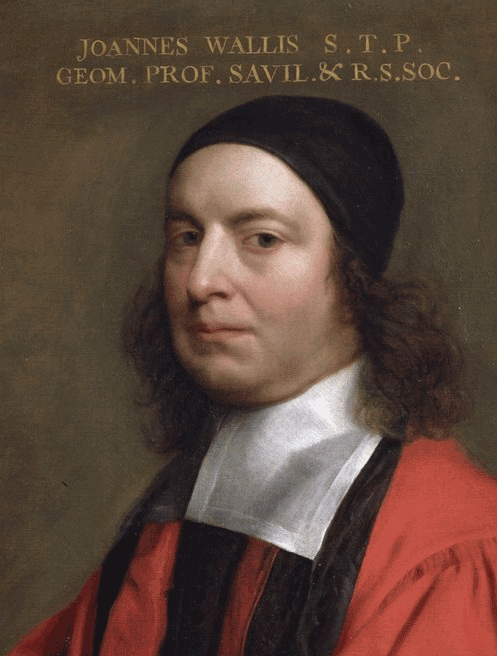

In the run up to the

publication in 1656 of Wallis’ book

Arithmetica infinitorum,

Christiaan Huygens and John Wallis have an extensive correspondence between June

1655 and September 1656.

The

last letter of Wallis to Huygens is from 22 August 1656 and Huygens’ answer to

Wallis is from September 1656. No mention at all in the entire correspondence of

anything horological. At this moment Wallis is the only Englishman Huygens is

corresponding with.

(13

It takes over two years for another letter from John to Christiaan.

(14

Confirmed by recently

rediscovered and published information from English archives Ahasuerus

Fromanteel I appears to have developed more and more into a technical instrument

and apparatus maker. He produces pumps and fire engines, but also telescopes,

boxes, lenses, hydrometers, blown glass 'laboratory' tools, automata, dredgers,

etc. etc. Beside all this he also makes clocks.

(15

From the

correspondence of Samuel Hartlib we now know that in the 1650’s Fromanteel is

concentrating on the duration of clocks and their running as accurately as

possible. In Fromanteels’ catalogue or list we can order ‘A

watch or standing clock to goo a weecke or a month or a year with once winding

up and yet to goo as true as one that is wound up every day’. He even makes

a ‘rolling ball clock

(16.

In 1657 we read

‘… A clock of Fromantils

… his new invented Clock of Motion to goe without being wound up a weeke or

month or longer’.

(17

Later the same year there is an announcement that ‘Fromantil

hath made a clock that needs not be wound up within a month’.(18

Ahasuerus Fromanteel I receives the Freedom of the City of London on 14 January

1656 and subsequently, after intervention of Cromwell, the Lord Protector, also

the Freedom of the Clockmakers’ Company. Only then he is allowed to make, sign

and sell clocks himself in the City of London.

(19

In the period before the invention of the pendulum

clock Christiaan Huygens is primarily concerned with mathematics and astronomy

(see the correspondence in Oeuvres

Complètes). He is mainly corresponding with people in Holland and France,

like Frans van Schooten, Claude Mylon, Blaise Pascal, Gilles Personne de

Roberval, Johannes Hevelius, Jean Chapelain.

(20

Jean Chapelain

Between 28 June and 19 December 1655

Christiaan is in Paris, together with his brother Lodewijk and cousin Philips

Doublet (21.

All 1656 and 1657 he is residing in Holland (The Hague)

(22

On 25 December 1656 Christiaan Huygens has his Eureka

moment by finding the application of the pendulum to the clock. On 26 December

of the next year, he writes in a letter to Ismael Boulliau ‘Yesterday

it was exactly a year ago that I made the first model of this type of clock…’.

(23

In a letter of the 12th of January 1657 to his tutor

the mathematician Professor Frans van Schooten we read ‘These

days I found the construction of a clock of a new generation, with times so

exact as the diameter, with its help I have no small hope to be able to

determine the longitude at sea’.

(24

Christiaan writes to Claude Mylon on 1 February 1657

‘I will also share with him a new

invention, that must be of great use in astronomy, and that I hope to

successfully use finding the longitudes. You will hear of it soon.’ With him

is meant Monsieur Bulliaut - Ismaël Boulliau, at that moment secretary of the

French ambassador in The Dutch Republic.

(25

Ismaël Boulliau

Claude Mylon writes back to

Christiaan on 12 April 1657 that his invention of the clock is found very

beautiful by all whom he has told about it, and this will be even more so if

Huygens can make it independent of weight or spring. Then nothing would stand in

the way of solving the problem of longitude.

(26

On 18 May 1657 Claude Mylon writes

Huygens again that he is glad that Huygens is continuously perfecting his clock

further, he fervently hopes it will be just as good at sea as in the room, and

changes from dry to humid do not change it more than the change in weights.

(27

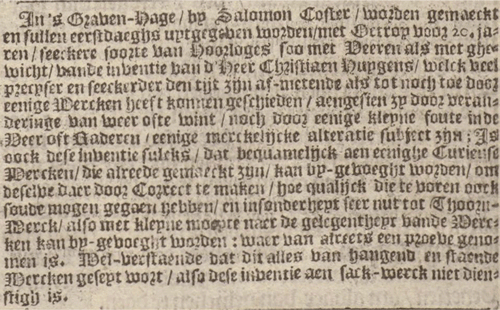

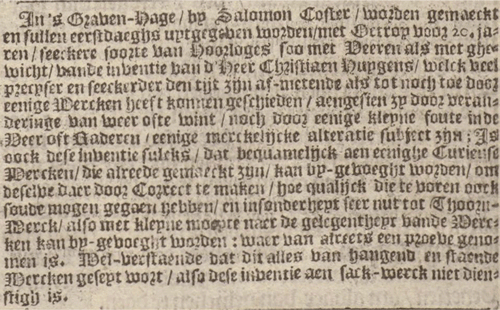

Salomon Coster’s advertisement in the

Tijdinghe 51, December 1657.

Boxing Day 1657 Christiaan Huygens asks Boulliau, by

then back in Paris, more details about the clock Ferdinando de' Medici, Grand

Duke of Tuscany allegedly had made, which shows a resemblance to Huygens’

invention, and whether this clock also has a pendulum.

This is the same letter in which Huygens tells it was

exactly a year ago he made the first model of a pendulum clock, and started in

June to show everyone interested the construction. He also writes he is busy

with the conversion of the turret clock in Scheveningen. The pendulum is almost

seven meters long (21 feet) and weighs approximately 20 kilo’s (40 or 50

pounds). By now he also urges Boulliau not to do anything in Paris, not by his

own instructions or by anyone else’s …(28

Subsequently Huygens writes on 13 June 1658 in

another letter to Boulliau he wants to apply for a patent in Paris as well. The

application is prepared by the French ambassador in The Hague, so Boulliau can

present it to the French Chancellor.

(29

One week later (21 June) Boulliau answers Huygens that the French Chancellor

Seguier has refused his request up to three times, as he does not want all

French clockmakers coming after him screaming.(30

On 16 July 1658 Simon Douw applies for a patent for

‘his own invention’. Huygens and Coster together file a lawsuit against Douw(II

because of

infringement of their patent.(31

On 6 September

Huygens sends ‘Horologium’ to more

than 60 scientists at home and abroad.(32

The list includes two copies for Salomon Coster. Fromanteel is not on the list.

From the foregoing we can conclude Christiaan Huygens

had a number of possible reasons to publish

Horologium:

Rumours of a

pendulum clock in Tuscany, the claim Galileo had invented this and Treffler made

a clock following this principle.

The application for a patent by Douw and the process

against him.

Refusal of the French Chancellor Seguier to grant

Huygens his patent for the pendulum clock.

In the

meantime, on 16 June 1657 Coster gains the privilege by the States General of

the Dutch Republic. This means he is the only one allowed to use and sell a

pendulum clock, invented by Christiaan Huygens and made available to Coster, in

the Dutch Republic for a period of 21 years.(33

This is officially ratified by the States of Holland and West-Friesland, the

most important province, on 16 July 1657.(34 Huygens tells us later this is

also the time he starts showing the construction to everyone interested.(35

On 3 September

1657 the ‘Contract’ between John Fromanteel (then still apprenticed to his

father) and Salomon Coster, Master Clockmaker, is signed.(36

The agreement runs until

May (meydage) 1658. Afterwards John

returns to London.

Hartlib mentions in the early summer of 1658:

‘A Clock newly invented in the Low Countries that

need only once to bee wound in 7 days and hath not failed to go exactly for many

months together. It is made without a balance so that it will never change by

any weather? Fromantil hearing of it, is endeavouring to make the selfe-same

Clock. His clock presented to my Lord Protector is returned upon his owne

hands'.(37

On 3

June the same Hartlib mentions in a letter to Robert Boyle

(Irish

philosopher and chemist/alchemist):

'Sir Robert Honeywood, lately arrived out of the Low

Countries, tells of a singular invention found out there, of a clock that goes

most exactly true without a balance, which needs not to be wound up but once in

eight days, the price being 7lb sterling. Mr Palmer, who hath a shop as it were

of all manner of inventions, is to have one shortly: and Fromantile hearing of

it gives out confidently, that he is able to make the like, or rather to exceed

it'.

(38

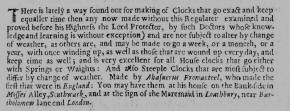

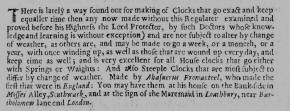

Fromanteel's advertisement October 1658

On 28 October 1658 Fromanteel publishes his famous

advertisement in the Mercurius Politicus

about the availability of a new type of clock. Right below this advertisement,

there is a second one in which he recommends his new pump, that not only can

quench fire, but also can spray pests from trees and hops, watering the gardens,

clothes and the like.

(39

As already

mentioned, the agreement between John Fromanteel and Salomon Coster is

signed on 3 September 1657. At this time John is

still apprenticed to his father for five

years and is 19 years of age. Next to care for his employee (beer, fire

and light), as a good employer should, to make his employee as

productive as possible, Coster will pay John 20 Guilders for every

completed piece of work and no more than 18½ Guilders if Coster supplies

the copper and steel.

(40

The Coster/Fromanteel contract does not give any information about

what type of timepiece is meant by horologien, because further

specification is lacking.

(41

Pieter Visbagh, another renowned Dutch

clockmaker, is apprenticed to Coster from 1 May 1645 onwards for nine

years. This is documented in the learning agreement between them,

drafted and signed almost a year later, on 31 January 1646. It is agreed

that during the first three years of the agreement Pieter is not

residing at Coster’s. After these three years Coster will provide board

and lodging. In the 8th year Pieter will additionally receive

a wage of 100 Guilders, doubled to 200 Guilders the next and last year.

At the end of this apprenticeship Pieter is 21 years of age.

(42

In the learning agreement of

Christiaan Reijnaert, aged 12 at the start (November 1655), we read:

“…

to live with and taken care of by the same, through food, drink,

clothing, clean washing, everything that is needed for nourishment”

(III.

Coster will receive from the uncles of Christiaan 50 Guilders for the

entire apprentice period of ten years. After completion of these ten

years of apprenticeship Christiaan is not sent away just like that. He

receives from Coster 100 Guilders and as much clothing as belongs to a ‘moral

trousseau’.

After Salomon Coster’s death, when

Pieter Visbagh takes over the workshop, he will also take over this

agreement.

(43

CONCLUSIONS

CONCLUSIONS

From the above

mentioned historical resources, we learn that Christiaan Huygens is in

The Hague all of 1656 and 1657. Ahasuerus Fromanteel I is the entire

same period in London. We know Ahasuerus’ son John was also in The Hague

from 3 September 1657 until 1 May 1658. However no correspondence, no

connection and no other proof of anything else between Huygens and the

Fromanteels can be found. The name Fromanteel does not occur even once

in one of the first four volumes of

Oeuvres Complètes (spanning

1638-1663). In contrast other ‘craftsmen’ are mentioned by Huygens

frequently:

● OC Huygens Vol.2

(1657-1659), pages:

Coster (Salomon).

125, 209, 235, 236, 241, 244, 245, 246, 247, 272,

281, 289, 290, 291, 314, 317, 327, 331, 372, 382, 419, 420, 439, 440,

473, 483, 486, 527, 540.

Hanet. 281, 294, 319, 372, 381, 382, 419, 454,

473, 483, 486, 527.

● OC Huygens Vol.3

(1660-1661), pages:

Coster

(Samuel). 4, 11, 84

Coster (Veuve Samuel)

à

Hartloop (Jannetje Hartmans) 4, 98, 284.

Hanet. 4, 8, 10, 16,

19, 23, 25, 50.

Treffler (Filippus). 483, 484.

● OC Huygens Vol.4

(1662-1663), pages:

Hooke (Robert).

218, 221, 275, 320, 359, 366, 437,438.

Oosterwyk (Severyn). 324, 411, 418, 424, 430, 434, 452, 456, 460, 477,

478.

Thuret. 110, 270.

If Fromanteel would have been involved in the very

early development of the pendulum clock, right after the invention, some

reference should have been found in the very extensive collection of

correspondence of Christiaan Huygens in

Oeuvres Complètes or in the

Dutch and English Archives.

Even if an apprentice of 19 years

of age, John Fromanteel, needed a period of 8 months to explain how to

make a pendulum clock to Salomon Coster, more than 12 years a Master

Clockmaker, where did John Fromanteel get this knowledge? His father?

Without any demonstrable connection to Christiaan Huygens?

There is

only the ‘Contract’ between John Fromanteel and Coster, which is not

much different from any of the other learning or apprenticeship

agreements. It also does not differ much from and is very comparable

with a modern internship towards the end of a training, with the benefit

for Coster of an already more experienced assistant and for Fromanteel

to learn about the new sensation: the pendulum clock.

By all

means, Fromanteel seems too commercial, certainly in view of his list

and the advertisements, to settle only for the very minimal and even

nowadays unknown and unproven benefit of scientific satisfaction. Was it

not just the information his son John brought back from The Hague, that

he needed to make a pendulum clock?

Do we not get a very logical

sequence of events, also substantiated by all historical sources: End of

‘Contract’ in May 1658 à John and Ahasuerus build their own version of

the pendulum clock during the summer

à

Huygens publishes and circulates Horologium in September 1658

à

Fromanteel publishes his advertisement in October 1658.

Huygens’

invention of the pendulum clock, in the form of Coster clocks, spreads

at a tremendous ‘commercial’ pace all over Europe, well before the

advertisement by Fromanteel. We know that before the end of 1657 a

‘Coster clock’ is in Tuscany. In an inventory of 1690 a clock signed by

Coster is mentioned to have arrived on 25 September 1657, as the first

pendulum clock in Italy. Treffler used this clock as example to make his

own. The movement of this latter clock is still existent today.

(44

From

Huygens’ correspondence we know a great many pendulum clocks are shipped

from The Hague to Paris, mainly by mediation of Nicolas Hanet.

We

know nothing, no clock or movement, description, correspondence, nor any

other source or anything else that would give a reason to put the very

first development of the pendulum clock with Fromanteel. There is no

direct proof at all. Moreover, any activity regarding pendulum clocks

from Huygens and/or Holland to England dates only after 1660, when the

trials with pendulum clocks at sea start. Christiaan Huygens comes over

to England for the first time in 1661.

(45

Only on this trip, in 1661, Christiaan visits the workshop of

Fromanteel, together with John Evelyn.

(46

But even then several of

these ‘regulators’ are being imported from The Hague to England.

(47

John

Evelyn

On the

other hand we know Coster and Huygens immediately after the invention

started to work on further improvements and applications of the pendulum

clock. One of their common projects is the turret clock of the church in

Scheveningen. On Boxing Day 1657 Huygens indicates he is working on the

conversion of the clock.

On 23 January 1658

Coster writes to Huygens that he is busy working on the clock in

Scheveningen, the clock has run all night, the pendulum weight is 50

pounds, but Coster wants to make several changes, as the movement runs a

quarter of an hour slow in 14 hours. He will take a look again next day.(48

Of the currently known early

pendulum clocks, none, neither from Coster nor from Fromanteel, are

‘scientific’ clocks. The earliest known clocks with a ‘three foot

pendulum’ all have a ‘scientific dial’ (large minute ring, small hour

ring, and a (small) seconds ring) all date from around or just after

1670, when this layout was first seen on the second edition of sea

clocks. The movements of all these scientific clocks are all in line

with the design presented in letters from Huygens around that time and,

a bit later, also published in Horologium Oscillatorum. The well-known

drawing exactly represents the layout of the movement of all presently

known clocks of this type.

(49

The movement of

Huygens’ own clock, signed Thuret

à Paris, currently in the collection of Museum Boerhaave, fully

meets this requirement.

Again, no sign of Fromanteel being involved in any of this; never does

he anywhere claim the invention. He also never applies for a patent in

England.

endsection

Also the

connection between the Huygens family and Ahasuerus Fromanteel through

Cornelius Drebbel is unlikely and illogical. Constantijn Huygens sr. and

Drebbel have met when they were both in London in 1621/22.(50

As a result Huygens sr. developed and kept a more than average interest

in Drebbel’s inventions. In 1622 Fromanteel was only 15 years of age,

while Christiaan was not even born.

Drebbel died in 1633. From the

‘Hartlib Papers’ we know no more than that Fromanteel once made a box

for Drebbel’s lenses and later started to make lenses himself.(51

No

more, no less. Even more far-fetched is the claim Fromanteel was in

Prague with Drebbel to study German clock making. When we know for

certain Drebbel was in Prague in 1610, Fromanteel was only 3 years of

age, far too young to show already any signs of a promising clockmaker.

Later trips are nowhere confirmed and also then Fromanteel would not

have reached the apprentice age yet. Anything here is purely

speculative.

Both father and son Huygens do not mention the name Fromanteel anywhere

in their extensively recorded correspondence. Once again any relation is

purely speculative.

End

of this section, click

here to continue.

NOTES NOTES

|

|

|

|

I |

A member of the Supervisory Board of a higher educational institution. |

|

II |

Simon Douw (ca.1620-1663) 'Horlogiemaecker der Stadt Rotterdam',

clockmaker of the city of Rotterdam. Amongst others he built the

movement for the clock of the Rotterdam Exchange (1660-1663) and

converted the turret clocks of the 'Geertekerk' in Utrecht (1659) and

the 'Grote Kerk' of Dordrecht (1663) to pendulum. |

|

III |

“te woonen ende van denselven besorcht te werden van cost, dranck,

cleedinge, ende reyne bewassen, bewrevingen, alle ‘tgeene wes tot

onderhout sal vereisschen” |

|

|

|

|

1 |

Richard Garnier & Leo Hollis, "Innovation & Collaboration, The early

development of the pendulum clock in London", 2018, 63 |

|

2 |

Richard Garnier & Leo Hollis, "Innovation & Collaboration, The early

development of the pendulum clock in London", 2018, 70 |

|

3 |

Richard Garnier & Leo Hollis, "Innovation & Collaboration, The early

development of the pendulum clock in London", 2018, 83 |

|

4 |

Richard Garnier & Leo Hollis, "Innovation & Collaboration, The early

development of the pendulum clock in London", 2018, 84 |

|

5 |

Christiaan Huygens, "Horologium", Preface, Translated from Latin:

Tijdschrift voor Horlogemakers, 1e Jaargang No.5 1 Maart 1903 |

|

6 |

Anita McConnell,

"Fromanteel, Ahasuerus (bap. 1607, d. 1693)", Oxford Dictionary of

National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, online reference /

Richard Garnier & Leo Hollis, "Innovation & Collaboration, The early

development of the pendulum clock in London", 2018, 72 |

|

7 |

Brian Loomes, "Country Clocks and their London origins", 1976, 34-35 |

|

8 |

Hans Kreft, "Rediscovering the Fromanteel Story", article in the Dutch

Kunst & Antiekjournaal (August 2003), lecture at Schoonhoven NL

(September 2003), published Horological Foundation website, where

translated and adapted by R.K.Piggott. |

|

9 |

Marriage certificate Salomon Coster - Jannetje Harmens, Gemeentearchief

Delft, Collection DTB nr. 14, inv. 125, fol 109, Archive research and

transcription performed by Victor Kersing and Rob Memel. |

|

10 |

Victor Kersing en Rob Memel, "Salomon Coster, de Haagse periode",

lecture AHS-DS 10 May 2014; article Tijdschrift 4, December 2014 |

|

11 |

Charlotte Lemmens, Constantijn & Christiaan, "Een Gouden Erfenis - Het

leven van Christiaan Huygens 1629-1695", 139-159 |

|

12 |

Jeremy Lancelotte Evans, "Clockmakers’ Company Masters and their

Apprentices.", Transcribed from Atkins’ list of 1931, 56. |

|

13 |

Oevres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, Tome Premier, correspondance

1638-1656, Martinus Nijhoff, 1888 |

|

14 |

Oevres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, Tome Deuxième, correspondance

1657-1659, Martinus Nijhoff, 1889, No. 497 |

|

15 |

Rebecca Pohancenik, "The Intelligencer and the Instrument Maker: Early

communications in the development of the pendulum clock", Antiquarian

Horology, Volume 31 no 6, (December 2009), 750. |

|

16 |

HP 71/19/1A. In this article I made use of the work and the article of

Rebecca Pohancenik, "The Intelligencer and the Instrument Maker: Early

communications in the development of the pendulum clock", Antiquarian

Horology, Volume 31 no 6, (December 2009), 756. |

|

17 |

HP 29/6/1A-12B. In this article I made use of the work and the article

of Rebecca Pohancenik, "The Intelligencer and the Instrument Maker:

Early communications in the development of the pendulum clock",

Antiquarian Horology, Volume 31 no 6, (December 2009), 753. |

|

18 |

HP 29/6/13A. In this article I made use of the work and the article of

Rebecca Pohancenik, "The Intelligencer and the Instrument Maker: Early

communications in the development of the pendulum clock", Antiquarian

Horology, Volume 31 no 6, (December 2009), 753. |

|

19 |

Brian Loomes, "Country Clocks and their London origins", 1976, 38-39 |

|

20 |

Oevres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, Tome Premier, correspondance

1638-1656, Martinus Nijhoff, 1888 |

|

21 |

Oevres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, Tome Premier, correspondance

1638-1656, Martinus Nijhoff, 1888, p. 335 note 1 and Oevres Complètes de

Christiaan Huygens, Tome Quinzième, Observations Astronomiques.

1658-1666, Martinus Nijhoff, 1925, p. 193 |

|

22 |

Oevres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, Tome Premier, correspondance

1638-1656, Martinus Nijhoff, 1888 |

|

23 |

Oevres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, Tome Deuxième, correspondance

1657-1659, Martinus Nijhoff, 1889, No. 443 |

|

24 |

Oevres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, Tome Deuxième, correspondance

1657-1659, Martinus Nijhoff, 1889, No. 368 |

| 25 |

Oevres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, Tome Deuxième, correspondance

1657-1659, Martinus Nijhoff, 1889, No. 370 |

|

26 |

Oevres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, Tome Deuxième, correspondance

1657-1659, Martinus Nijhoff, 1889, No. 382 |

|

27 |

Oevres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, Tome Deuxième, correspondance

1657-1659, Martinus Nijhoff, 1889, No. 388 |

|

28 |

Oevres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, Tome Deuxième, correspondance

1657-1659, Martinus Nijhoff, 1889, No. 443 |

|

29 |

Oevres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, Tome Deuxième, correspondance

1657-1659, Martinus Nijhoff, 1889, No. 490 |

|

30 |

Oevres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, Tome Deuxième, correspondance

1657-1659, Martinus Nijhoff, 1889, No. 492 |

|

31 |

Oevres Complètes de Christiaan

Huygens, Tome Deuxième, correspondance 1657-1659, Martinus Nijhoff,

1889, Appendice IV bij No. 523 |

|

31 |

Oevres Complètes de Christiaan

Huygens, Tome Deuxième, correspondance 1657-1659, Martinus Nijhoff,

1889, Appendice IV bij No. 523 |

|

32 |

Oevres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, Tome Deuxième, correspondance

1657-1659, Martinus Nijhoff, 1889, No. 511 |

|

|

|

|

Back to end of previous section.

Back to end of previous section.

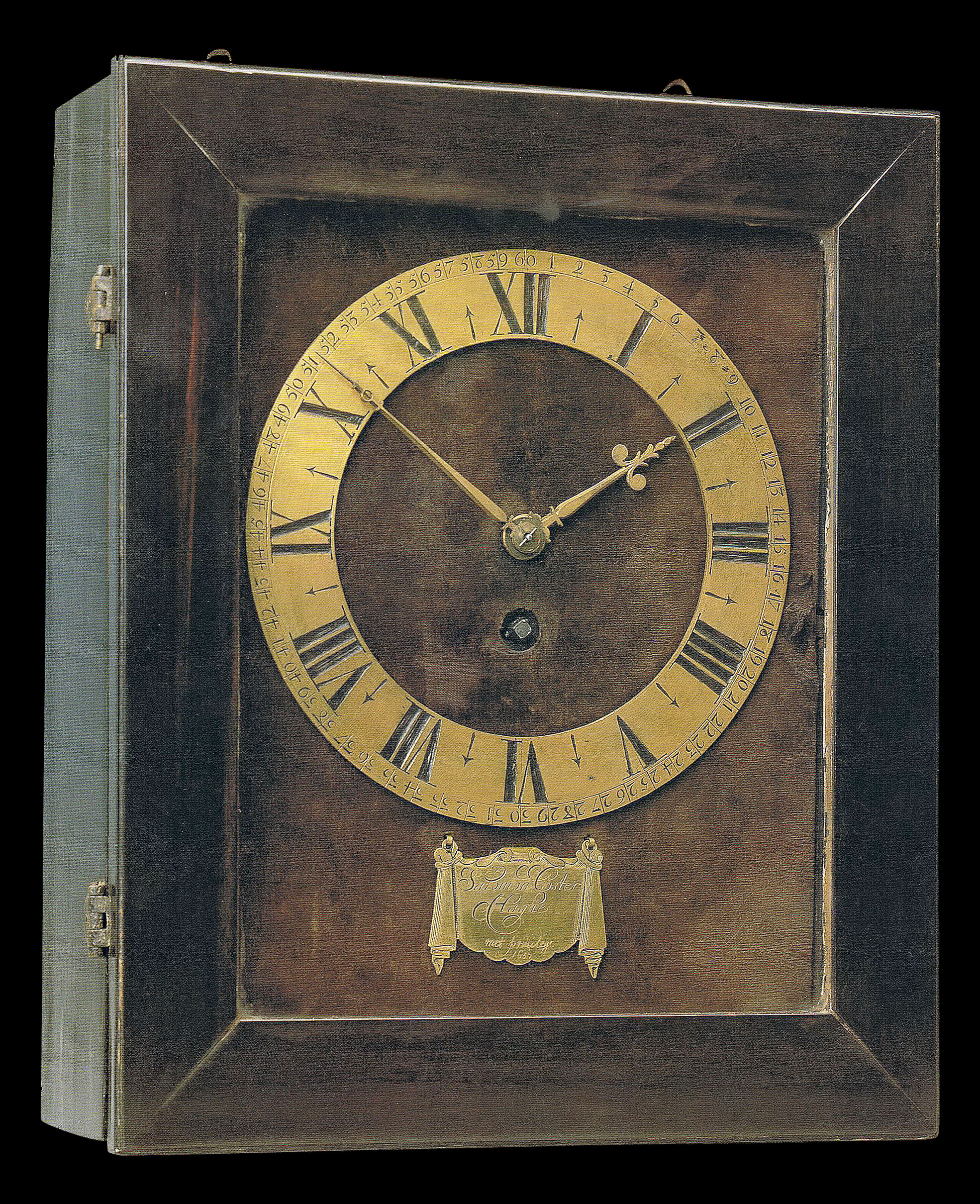

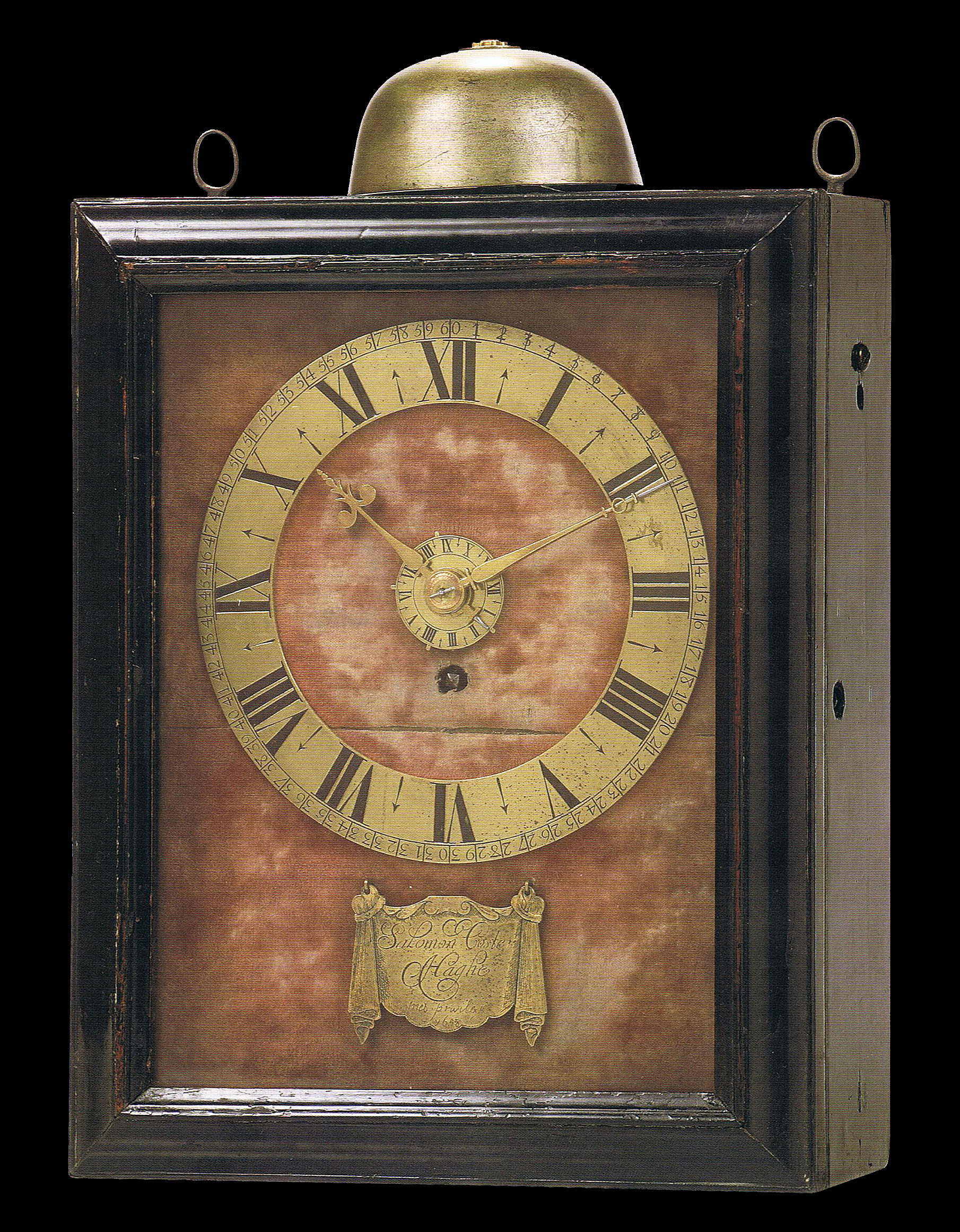

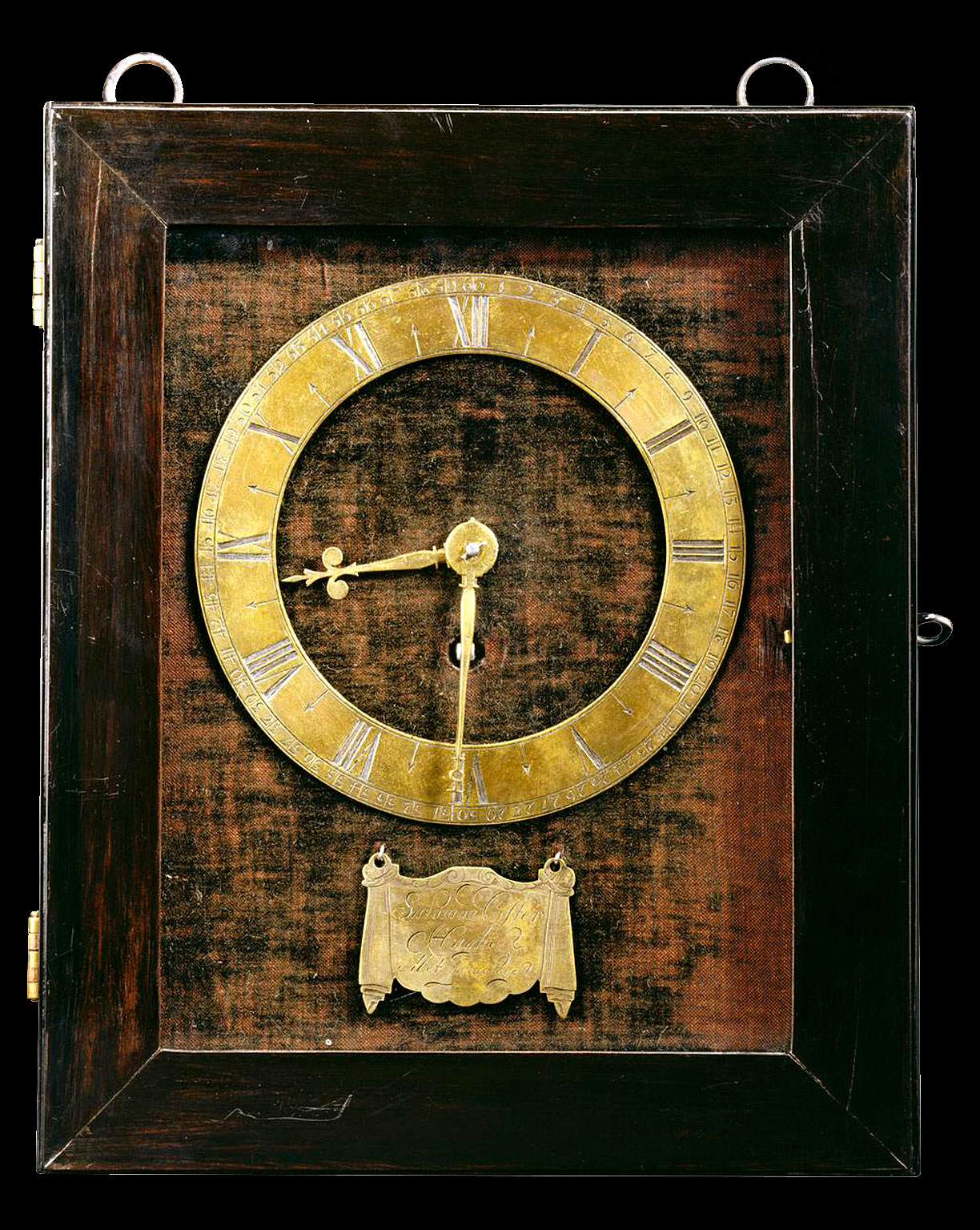

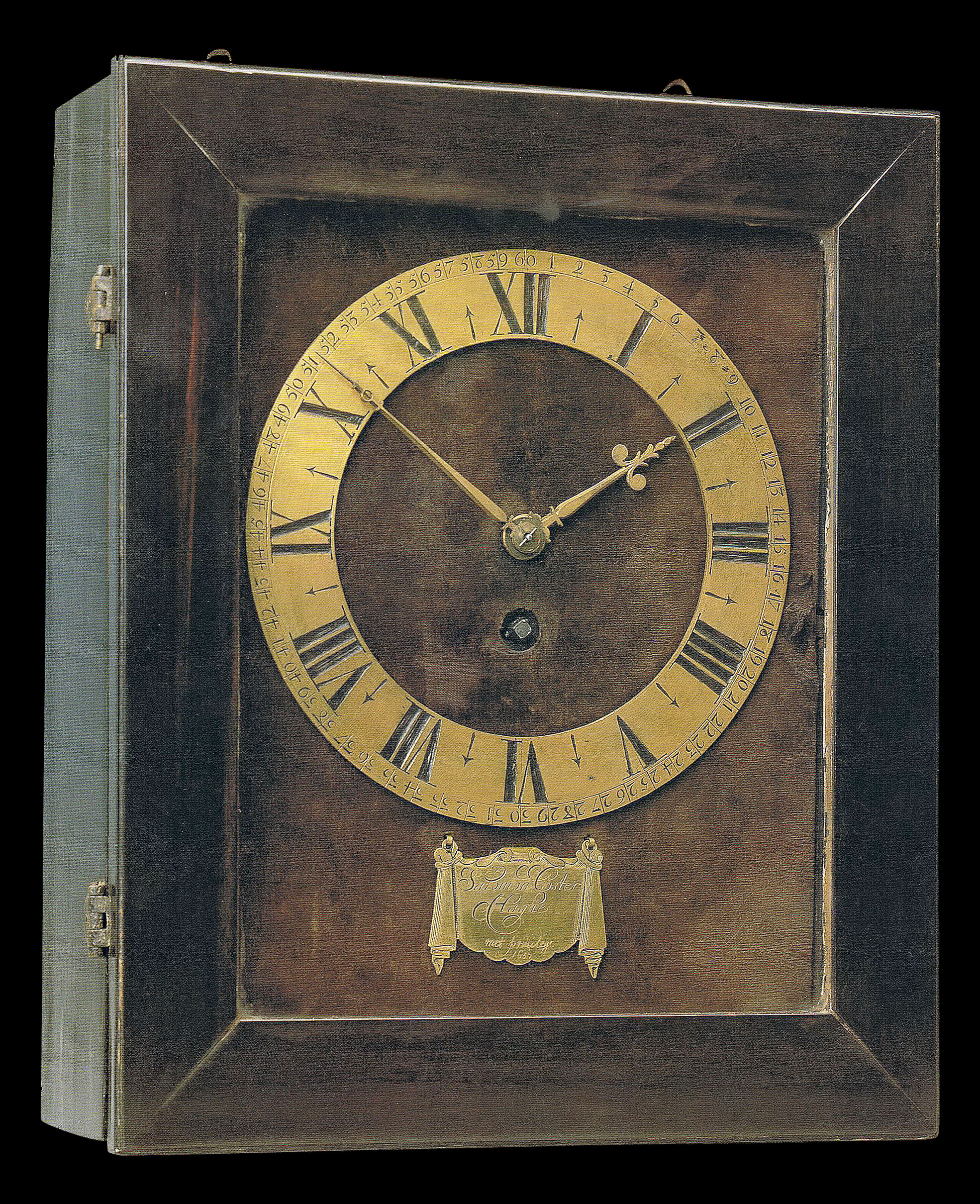

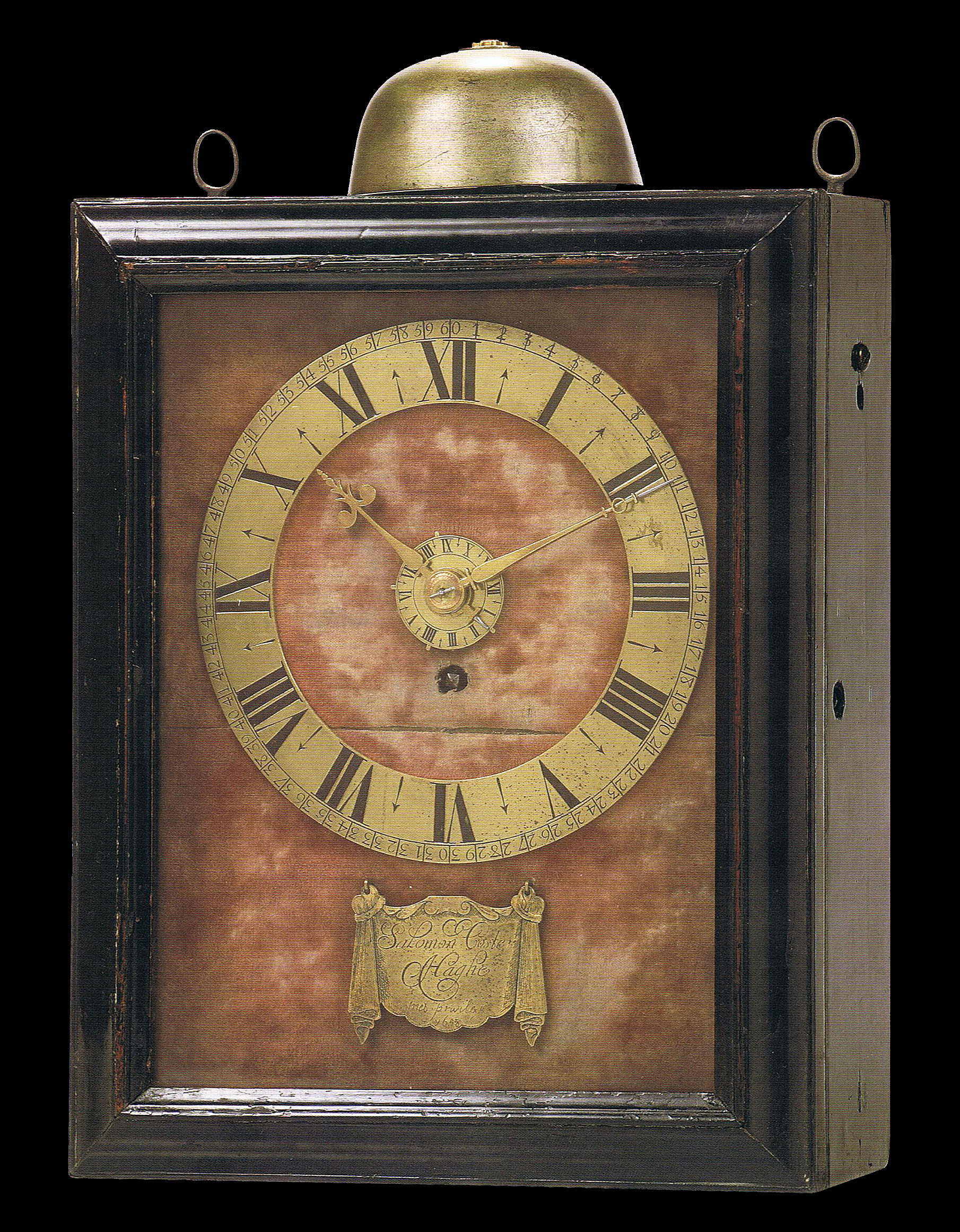

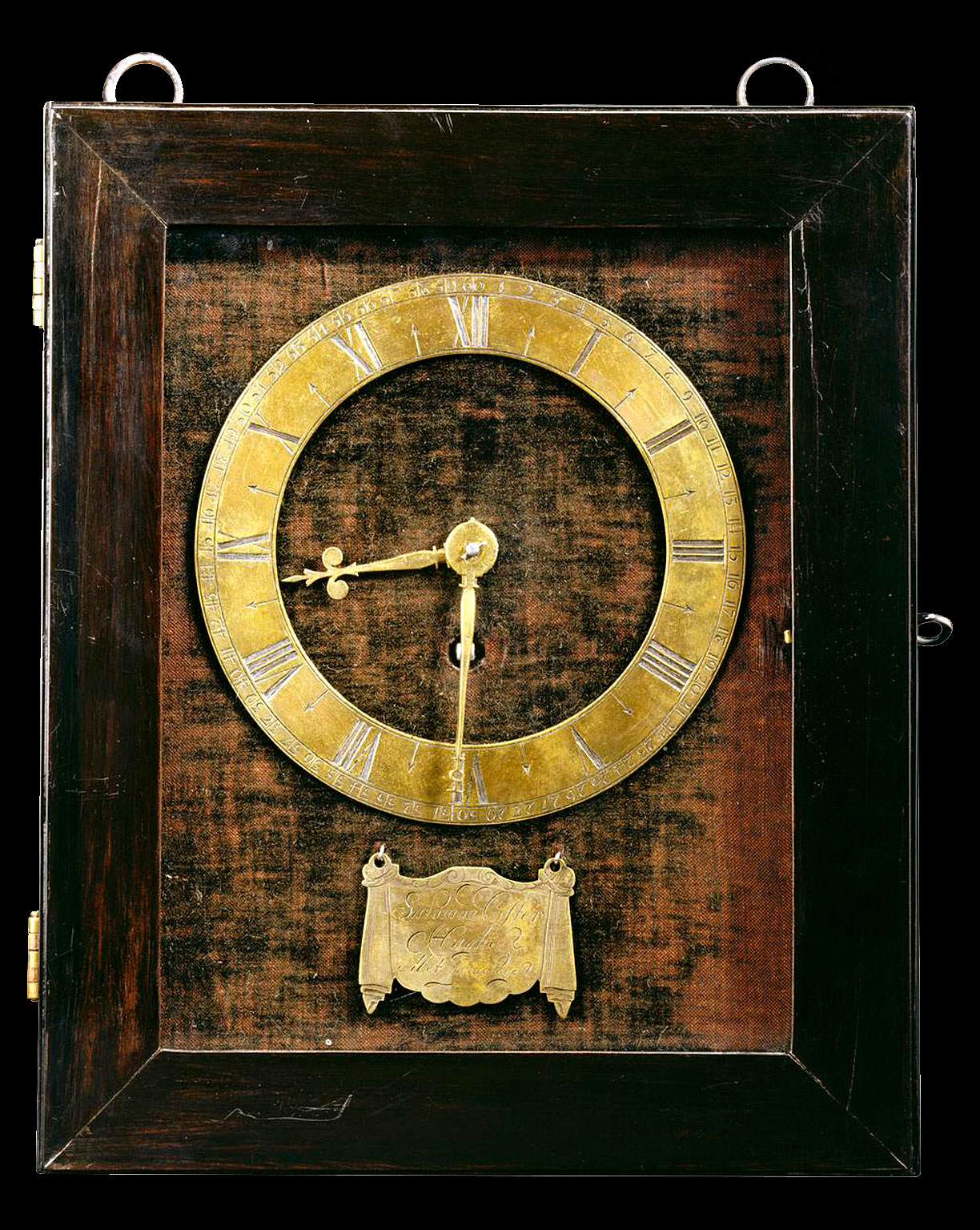

THE CLOCKS

THE CLOCKS

The early pendulum clocks still

existent today are all of the same, nowadays well known type. A

wooden case with a single chapter ring and central hour and minute

hands.

In Holland we see a continued adherence to the principles of

the first clocks, one single barrel for both going and striking train, a

velvet covered dial plate, signature below the chapter ring (creating a

rectangular dial plate) on a tip-up signature shield hanging over an

access hole in the dial plate for starting the pendulum. The pendulum is

suspended from a small wire and trapped in a crutch connected to the

verge escapement. The entire movement is hanging on the dial plate which

turns out to the front, there is no backdoor.

In England, fairly

quickly after the invention makes the crossing, there is an independent

development. There is no velvet on the square dial plate. We see

spandrels in the corners around the chapter ring and a quick return of

the use of a fusee next to the spring barrel, in combination with a

pendulum directly fixed to the verge. The signature is engraved directly

on the dial plate. The movement will almost immediately get a separate

barrel for both going and striking train. After the first ‘box’ clocks

the movement is mounted in the case and soon after the case is also

provided with a back door.

Every artefact, made in a certain period, inherits

innovations, customs and developments from an earlier period. All clocks

in the 2nd half of the 17th century have to do

with the legacy and influence of Italy and the German empire of the 16th

and early 17th century. The renaissance clocks, arts and

objects from this era and area influence all subsequent developments or

these later developments revert to these. For instance the use of wooden

cases, spring barrels and architectural designs are a direct

illustration of this.

Less clear but certainly remarkable are

the ‘square pillars’ used by Coster for his movements and the rapid

change to ‘turned pillars’ by Fromanteel (we know only five Fromanteel

signed clocks with ‘square pillars’).(52

Then anew the application of a fusee in combination with a spring barrel

by Fromanteel, and his making use of iron hands are other examples of

this influence, while Coster switches to silver or gilded brass hands.

When we compare the movements of this period, we

cannot miss the obvious developments in time. Coster dies too early to

say anything about the further development from

his part and we also do not

see much development of the movements from his successors (Oosterwijck,

Visbagh, Hanet en Reijnaert). But we clearly do see rapid developments

at the English side. Here the movements evolve immensely in increasing

duration, in the addition of striking and musical works, calendars and

other complications and of course, after a few years, the introduction

of the anchor escapement.

Therefore we can only conclude we

have to use another dating of the earliest pendulum clocks as used in

the exhibition and catalogue. This different dating, by the way, is

generally used and accepted in most other sources and literature as

well.

1657

Salomon Coster Haghe met privilege 1657

(N1) Museum

Boerhaave, Leiden

-kopie.png)

1657

Salomon Coster Haghe met privilege 1657

(N2) Collection

Zuylenburgh - Bert Degenaar

1658

Salomon Coster Haghe met privilege 1658

(N5) Collection John

C. Taylor

1658

Salomon Coster Haghe Met privilege

(N4) Science Museum,

London

-kopie.png)

1658

A. Fromanteel London Fecit 1658

“Lyme Park Fromanteel”

Collection The National Trust

%20kopie.png)

1659

A Fromanteel Londini

Collection John C. Taylor

1659

A Fromanteel Londini

“Bass Fromanteel” Private collection

1659

Salomon Coster Haghe Met privilege

(N8) Collection Museum of

the Dutch Clock

1659

Simon Bartram

Collection John C. Taylor

1659-1660

Salomon Coster Haghe Met privilege

(N10) Former

collection Mario Crijns

-kopie.jpg)

1659-1660

Ahasuerus Fromanteel Londini fecit

Private collection

_1659-1660-kopie.jpg)

1659-1660

Ahasuerus Fromanteel

Londini Fecit

Collection John

C. Taylor

TIMELINE

TIMELINE

|

25 Feb. 1607

|

Ahasuerus Fromanteel I born in

Norwich

|

|

Ca. 1622 |

Salomon Coster born in Haarlem |

|

14 Apr. 1628

|

Christiaan Huygens born in The

Hague

|

|

1631

-Nov. 1632

|

Ah. Fromanteel I joins the Blacksmiths’ Company and the Clockmakers’

Company as Free Brother

|

|

Nov. 1632

|

Ah. Fromanteel I joins the Clockmakers’ Company by redemption (purchase)

as Free Brother

|

|

Ca. 1638

|

Johannes (John) Fromanteel born

|

|

31 Jan. 1646 |

Salomon Coster is named as a master clockmaker (meester

horologiemaecker)

in a notarial document in which master tailor

Rerick Eraerts entered into a contract with Salomon Coster for the

apprenticeship of his son Pieter Rerick (Visbach). |

|

5 Apr. 1652

|

John Fromanteel is bound before the Court to his father as apprentice

|

|

Jun.

1655 –

Sep. 1656

|

In the run up to the publication in 1656 of

Wallis’ book Arithmetica

infinitorum, Christiaan Huygens and John Wallis have an extensive

correspondence on Mathematics.

At that moment Wallace is

the only Englishman Christiaan is corresponding with.

|

|

28

Jun.1655 –Dec.1655 |

Chr. Huygens is in Paris

(together with his younger brother Lodewijk and cousin Philips Doublet)

|

|

1 Nov. 1655 |

Apprentice contract between Salomon Coster and Christiaen Reynaerts.

|

|

1656 & 1657

|

Chr. Huygens is in Holland (The Hague).

|

|

14 Jan. 1656

|

Ah. Fromanteel I receives the

Freedom of the City of London and subsequently, after intervention of

Cromwell, the Lord Protector, also the Freedom of the Clockmakers’

Company.

|

|

25 Dec. 1656

|

Chr. Huygens invents the

application of the pendulum to the clock.

|

|

1657 1st half

|

Hartlib records,

'Mr Palmer of Gray’s Inn hath Mr. Fosters new invented Dial. A clock of

Fromantils of 200lb who will have ready within 6 weekes his new invented

Clock of Motion to goe without being wound up a weeke or month or

longer'.

|

|

12 Jan. 1657

|

Christiaan Huygens writes his former tutor,

the mathematician Professor Frans van Schooten ‘These

days I found the construction of a clock of a new generation, with times

so exact as the diameter, with its help I have no small hope to be able

to determine the longitude at sea’

|

|

1 Feb. 1657

|

Chr.

Huygens writes to Claude Mylon

‘I

will also share with him1 a new invention, that must be of

great use in astronomy, and that I hope to successfully use finding the

longitudes. You will hear of it soon.’

1

With him is meant Ismaël Boulliau, at that moment secretary of the

French ambassador in The Dutch Republic.

|

|

12 Apr. 1657

|

Claude Mylon writes to

Christiaan Huygens that his invention of the clock is found very

beautiful by all whom he has told about it, and this will be even more

so if Huygens can make it independent of weight or spring. Then nothing

would stand in the way of solving the problem of longitude.

|

|

18 May 1657 |

Claude Mylon writes Huygens that he is glad that Huygens is continuously

perfecting his clock further, he fervently hopes it will be just as good

at sea as in the room and changes from dry to humid do not change it

more than the change in weights. |

|

June 1657 |

Huygens writes and explains to Kechelius how he discovered and invented

the adaptation of the pendulum to a movement. |

|

18 May 1657

|

Claude Mylon writes Huygens that

he is glad that Huygens is continuously perfecting his clock further, he

fervently hopes it will be just as good at sea as in the room and

changes from dry to humid do not change it more than the change in

weights.

|

|

16 Jun.

1657

|

Salomon Coster gains the

privilege by the State General of the Dutch Republic. This means he is

the only one allowed to use and sell a pendulum clock, invented by

Christiaan Huygens and made available to Coster, in the Dutch Republic

for a period of 21 years.

|

|

16 Jul. 1657

|

The States of Holland and West-Friesland officially ratify the patent.

|

|

3 Sep. 1657

|

Contract signed at The Hague, The Netherlands, between John Fromanteel

of London (then still nominally an apprentice to his father) and Salomon

Coster of The Hague. Fromanteel under the contract to remain at Coster's

expense, making horologien, until May 1658

|

|

25 Sept.1657 |

The first delivery of a Coster pendulum clock to the Grand Duke

Ferdinand II de' Medici in Florence. The manufacture of this clock must

have been

completed well before the arrival of John Fromanteel in

Coster’s workshop |

|

22

Dec. 1657 |

Salomon Coster announces in an advert in Tijdinghe uyt verscheyden

Quartieren (22 December 1657, no 51) his pendulum clocks, spring or

weight driven and made according to the patent of 16 June 1657, will be

available soon. Even conversion of public clocks is possible |

|

26 Dec. 1657

|

Christiaan Huygens asks

Boulliau, by then back in Paris, more details about the clock Ferdinando

de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany allegedly had made, which shows a

resemblance to Huygens’ invention and whether this clock also has a

pendulum.

This is also the letter in which Huygens

indicates it was exactly a year ago he made the first model of a

pendulum clock, and he started to show everyone interested the

construction in June 1657.

He also indicates he is busy with the

conversion of the turret clock in Scheveningen; the pendulum is almost 7

meters long and weighs about 20 kilos.

By now he also urges Boulliau not to do

anything in Paris, not by his own instructions or by anyone else’s …

|

|

Dec. 1657 - Jan. 1658 |

Huygens together with Salomon Coster in cooperation with blacksmith

Coenraad Harmenszoon Brouckman is busy with the conversion of the tower

clock in Scheveningen; the pendulum is almost 7 meters long and weighs

about 20 kilos |

|

3 May 1658 |

Salomon Coster in collaboration with Master blacksmith Bartholomeus

Wijnbron was commissioned to convert the turret clock of the Dom church

in

Utrecht to pendulum |

|

1658 early May

|

John Fromanteel departs from Coster's workshop in The Hague

|

|

1658 early summer

|

Hartlib reports ‘A

Clock newly invented in the Low Countries that need only once to bee

wound in 7 days and hath not failed to go exactly for many months

together. It is made without a balance so that it will never change

by any weather? Fromantil hearing of it, is

endeavouring to make the selfe-same Clock. His clock presented to my

Lord Protector is returned upon his owne hands'

|

|

3 Jun. 1658

|

Hartlib letter to Robert Boyle, saying,

'Sir Robert Honeywood, lately

arrived out of the Low Countries, tells of a singular invention found

out there, of a clock that goes most exactly true without a balance,

which needs not to be wound up but once in eight days, the price being

7lb sterling. Mr Palmer, who hath a shop as it were of all manner of

inventions, is to have one shortly: and Fromantile hearing of it gives

out confidently, that he is able to make the like, or rather to exceed

it'

|

|

13 Jun. 1658

|

Christiaan Huygens writes in a

letter to Boulliau that he wants to apply for a patent in Paris too. The

application is prepared by the French ambassador in The Hague, so

Boulliau can present it to the French Chancellor ...

|

|

21 Jun. 1658

|

Boulliau answers Huygens that

the French Chancellor Seguier has refused up to three times his previous

request, as he does not want all French clockmakers coming after him

screaming.

|

|

16 Jul. 1658

|

Simon Douw applies for a patent

for ‘his own invention’. Huygens and Coster together file a lawsuit

against Douw because of infringement of their patent.

|

|

6 Sep. 1658

|

Publication and distribution of Horologium by Christiaan Huygens;

Salomon

Coster is the only clockmaker who receives two copies of

Horologium

|

|

19 Oct. 1658 |

On request of Huygens the State of Gelderland officially ratifies the

patent to

Salomon Coster in collaboration with Jan van Call. (This

patent covers mainly

turret clocks) |

|

28 Oct. 1658

|

Ahasuerus Fromanteel advertises availability

of newly-invented pendulum clocks in

Mercurius Politicus

|

In addition for new and more detailed

information we refer to the publication of Ben Hordijk and Rob Memel

Salomon Coster the clockmaker of Christiaan

Huygens. The production and development of the first pendulum clocks in

the period 1657 – September 1658.

●

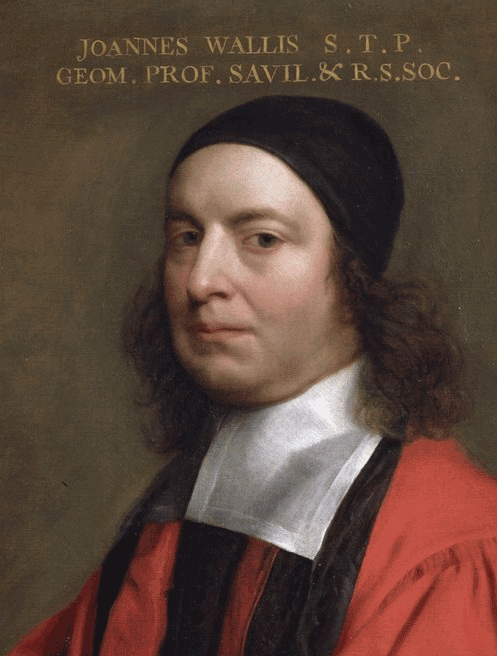

John Wallis (Ashford, 22 November 1616

- Oxford, 28 October 1703) was an English mathematician. The most

important of Wallis's works, Arithmetica

infinitorum, was published in

1656. In this treatise he showed how algebraic methods could be applied

to geometrical situations (after Descartes), like the calculation of the

area under the curve. infinitorum, was published in

1656. In this treatise he showed how algebraic methods could be applied

to geometrical situations (after Descartes), like the calculation of the

area under the curve.

He did preparational work in differential and

integral calculus. Using patterns in finite processes, he sought

formulas for infinite processes. He was an example for many

mathematicians, such as Newton, who built on Wallis' differential and

integral calculus.

●

Samuel Hartlib or Hartlieb (c. 1600 – 10

March 1662) was a versatile German-British scientist. As an active

promoter and expert writer in many fields, he was interested in science,

medicine, agriculture, politics and education. Hartlib had the

purpose of "registering all human knowledge and making it available for

study to all mankind". Before that, he had contact with anyone in the

age of the Commonwealth who meant intellectual matters and was

responsible for patents, disseminating information and promoting

education, passing on designs for calculators, double-script

instruments, seed machines and siege machines. His letters, in German

and English, are still the subject of study ... Hartlib had the

purpose of "registering all human knowledge and making it available for

study to all mankind". Before that, he had contact with anyone in the

age of the Commonwealth who meant intellectual matters and was

responsible for patents, disseminating information and promoting

education, passing on designs for calculators, double-script

instruments, seed machines and siege machines. His letters, in German

and English, are still the subject of study ...

●

Cornelis Jacobszoon Drebbel (1572 – 7

November 1633) was a Dutch engineer and inventor. He was the builder of

the first navigable submarine in 1620 and an innovator who contributed

to the development of measurement and control systems, optics,

chemistry, and the ‘perpetuum mobile’, a device with eternal movement.

In 1598 he obtained a patent for a water-supply system and a sort of

perpetual clockwork.

Around 1605 the Drebbel family moved to England,

probably at the invitation of the new king, James I of England (VI of

Scotland). He was accommodated at Eltham Palace. Drebbel worked there at

the masques, that were perf ormed by and for the court. He was attached

to the court of young Renaissance crown-prince Henry. He astonished the

court with his inventions. ormed by and for the court. He was attached

to the court of young Renaissance crown-prince Henry. He astonished the

court with his inventions.

Between 1610 and 1613 Drebbel resides on

invitation of Rudolf II at the court in Prague.

When Rudolf II was

stripped of all effective power by his younger brother Archduke

Matthias, Drebbel was imprisoned for about a year. After Rudolf's death

in 1612, Drebbel was eventually set free and went back to London.

In

1619 Drebbel showed a composite microscope to the Dutch ambassador in

London, Willem Boreel.

When in England, Constantijn Huygens, father

of Christiaan, was a regular visitor to Drebbel. Between 1618 and 1624

Huygens sr. visited England several times, as a diplomat in training.

From Drebbel he bought a camera obscura and a microscope.

Constantijn

Huygens transferred his interest in optics to his two oldest sons.

Christiaan had a booklet from Drebbel.

After the death of King James

I, Drebbel was employed in the service of the navy between 1626 and 1628

by Charles I, but without much success. As a result of which he lost his

job and income in 1628. Towards the end of his life, Drebbel was working

as innkeeper and brewer. He died in 1633.

●

Rules of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers

Minimum

age ‘apprenticeship’ is 14 years. Duration of the ‘apprenticeship’ is

7 years. After completion of the 7th year ‘apprenticeship’ the

apprentice becomes a ‘journeyman’ for a period of minimum 2 years

After the ‘journeyman’ period the ‘journeyman’ can become a ‘Freeman’ by

paying the ‘entry fee’.

During the ‘apprenticeship’ the apprentice is

bound to his ‘master’, but is allowed to service another ‘master’ during

this period. In the ‘journeyman’ period the ‘journeyman’ had to work

for one single ‘master’ as ‘workman’, for a period of 2 years, before he

could set up a business himself. During the ‘apprenticeship’ and

‘journeyman’ periods he is not allowed to sign under his own name, the

clock had to be signed under the name of the 'master' that was served.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

March

2019, Copyright:

(This article is subject to ongoing

revisions.)

LINKS

and FURTHER READING LINKS

and FURTHER READING

Chr.

Huygens' Œuvres Complètes.

(pdf)

Chr.

Huygens Horologium 1658.

(pdf)

Salomon Coster the clockmaker of Christiaan

Huygens. The production and development of the first pendulum clocks in

the period 1657 – September 1658.

|

|

Notes

continued: |

|

|

|

|

33 |

Oevres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, Tome Deuxième, correspondance

1657-1659, Martinus Nijhoff, 1889, Appendice II bij No. 523 |

|

34 |

Oevres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, Tome Deuxième, correspondance

1657-1659, Martinus Nijhoff, 1889, Appendice III bij No. 523 |

|

35 |

Oevres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, Tome Deuxième, correspondance

1657-1659, Martinus Nijhoff, 1889, No. 443 |

|

36 |

Haags Gemeentearchief - Toegangsnummer Oud notarieel 0372-01, inv. 322,

fol. 409.

Archive research

and transcription performed by Victor Kersing and Rob Memel. |

| 37 |

Rebecca Pohancenik, "The Intelligencer and the Instrument Maker: Early

communications in the development of the pendulum clock", Antiquarian

Horology, Volume 31 no 6, (December 2009), 753. |

|

38 |

The works of the Honourable Robert Boyle, ed T. Birch (London. 1744),

Vol. VI, pp.110-11. In this article I made use of the work and the

article of Rebecca Pohancenik, "The Intelligencer and the Instrument

Maker: Early communications in the development of the pendulum clock",

Antiquarian Horology, Volume 31 no 6, (December 2009), 754. |

|

39 |

Mercurius Politicus, issue number 439, October 21-28, 1658; as

reproduced in Penney, op.cit., 619-620.

In this article I made use of the work and the article of

David Penney, "The Earliest Pendulum Clocks:

A Re-Evaluation", Antiquarian Horology, Volume 31 No 5, (September

2009), 614-620. |

|

40 |

Haags Gemeentearchief - Toegangsnummer Oud notarieel 0372-01, inv. 322,

fol. 409.

Archive research

and transcription performed by Victor Kersing and Rob Memel. |

|

41 |

..te weten dat hij Fromanteel orologie…. zal voltrecken en

volmaecken. |

|

42 |

Haags Gemeentearchief - Toegangsnummer Oud notarieel 0372-01, inv. 20,

fol. 321.

Archive research

and transcription performed by Victor Kersing and Rob Memel. |

|

43 |

Haags Gemeentearchief - Toegangsnummer Oud notarieel 0372-01, inv. 110,

fol. 63.

Archive research

and transcription performed by Victor Kersing and Rob Memel. |

|

44 |

R. Plomp, "Spring-driven Dutch pendulum clocks 1657-1710", Interbook

(Schiedam), 1979, 15 |

|

45 |

Oevres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, Tome Troisième, correspondance

1660-1661, Martinus Nijhoff, 1889 No. 852 note

1 |

|

46 |

John Evelyn, "The Diary of John Evelyn", 1901, 346 |

|

47 |

Oevres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, Tome Troisième, correspondance

1660-1661, Martinus Nijhoff, 1889, No. 868 |

|

48 |

Oevres Complètes de

Christiaan Huygens, Tome Deuxième, correspondance 1657-1659, Martinus

Nijhoff, 1889, No. 452 |

| 49 |

Christiaan Huygens, "Horologium Oscilatorum", 1673, Pars Prima |

|

50 |

“Briefwisseling van

Constantijn Huygens” edited by J.A. Worp (old edition) - Part 1,

1608-1634, GS 15 p. LIV |

|

51 |

Worsley to Hartlib, 22 June 1648, HP 42/1/1 A. In this article I made

use of the work and the article of Rebecca Pohancenik, "The

Intelligencer and the Instrument Maker: Early communications in the

development of the pendulum clock", Antiquarian Horology, Volume 31 no

6, (December 2009), 750. |

|

52 |

Richard Garnier & Leo Hollis, "Innovation & Collaboration, The early

development of the pendulum clock in London", 2018, 144. |

|

|

|

|

-kopie.png)

-kopie.png)

%20kopie.png)

-kopie.jpg)

_1659-1660-kopie.jpg)

infinitorum, was published in

1656. In this treatise he showed how algebraic methods could be applied

to geometrical situations (after Descartes), like the calculation of the

area under the curve.

infinitorum, was published in

1656. In this treatise he showed how algebraic methods could be applied

to geometrical situations (after Descartes), like the calculation of the

area under the curve.  Hartlib had the

purpose of "registering all human knowledge and making it available for

study to all mankind". Before that, he had contact with anyone in the

age of the Commonwealth who meant intellectual matters and was

responsible for patents, disseminating information and promoting

education, passing on designs for calculators, double-script

instruments, seed machines and siege machines. His letters, in German

and English, are still the subject of study ...

Hartlib had the

purpose of "registering all human knowledge and making it available for

study to all mankind". Before that, he had contact with anyone in the

age of the Commonwealth who meant intellectual matters and was

responsible for patents, disseminating information and promoting

education, passing on designs for calculators, double-script

instruments, seed machines and siege machines. His letters, in German

and English, are still the subject of study ... ormed by and for the court. He was attached

to the court of young Renaissance crown-prince Henry. He astonished the

court with his inventions.

ormed by and for the court. He was attached

to the court of young Renaissance crown-prince Henry. He astonished the

court with his inventions.