PART 3/5

Dealing with and interpreting historical sources.

(Type

Ctrl+F

to find any text on this page)

THE

YEAR 1657

THE

YEAR 1657

In parts 1

and 2 we have identified

the main characters, mentioned in the book Innovation & Collaboration - The early

development of the pendulum clock in London

(Garnier & Hollis)(1,

based on historical facts. This third part deals with the year 1657 in which

the invention of Christiaan Huygens, the application of the pendulum in a clock

movement, was made into a working and commercial product. In addition, we will

discuss and denounce the research method that, especially from England, has

been used now for decades. It is striking, that this method always has a particular

underlying strategy: to reduce the role of Salomon Coster, and to a lesser

extent the role of Christiaan Huygens, to increase the role of the English

makers and in particular that of John or Ahasuerus Fromanteel.

As an example of this method,

we want to examine the new theory of Garnier & Hollis, based on facts, as

documented in the archives. This theory was widely promoted during the

beautiful exhibition Innovation & Collaboration, held at Bonhams in London

from 3 to 14 September 2018 and also recorded in the aforementioned book.

The

surprising conclusion of Garnier & Hollis is that John Fromanteel came from

London to The Hague to teach Salomon Coster, between September 1657 and May

1658, how to make a pendulum clock.

THE EXPERIMENTAL PHASE

THE EXPERIMENTAL PHASE

Before we go into the story

of Garnier & Hollis first the facts at a glance: the patent for the

application of the pendulum in a clock movement was granted by the States

General to Salomon Coster on 16 June 1657.(2

With this, Coster had the (exclusive) right for 21 years to make pendulum

regulated clocks in Holland and West-Friesland. Unfortunately, the patent

application itself has not yet been found or has been lost altogether, but it

obviously had been submitted some time before the conferment on 16 June.

This implies there was only a

period of at most a few months between the actual invention of Christiaan

Huygens (December 25, 1656) and the conferment of the patent. In the

experimental phase from January 1657 to the patent application, work will have

been done to make a functioning pendulum clock. Although nowhere has been

recorded who assisted Huygens during this first phase, the most likely

candidate is Salomon Coster. After all, he was the applicant for the patent.

Also at a later stage (December 1657), during the works in the church tower of

Scheveningen, Coster was obviously the right man to call upon when it involved

experiments with pendulum movements.(3

No other clockmakers assisting Huygens are mentioned in this first period.

THE PATENT

THE PATENT

Salomon Coster was at that

time one of the most important clock- and watchmakers in the Netherlands,

having made complicated box clocks and watches. Given the short time span

between the simple but brilliant invention of Huygens and the application of the

patent, it was apparently easy for Coster to construct four gearwheels between

two plates, a pendulum suspension and motion work. This new construction was much simpler than

the movements Coster had made so far.

After obtaining the patent in

June 1657, Coster will soon have found out that he had opened a new market and

that the expansion of labour capacity was desperately needed. He will have

sought cooperation in order to enlarge the current production and to be able to

serve the new market of the pendulum clock.

As an advanced apprentice

John Fromanteel fitted well in this picture. He was a 5th-year

apprentice, not yet a journeyman, so not yet an accomplished clockmaker. On the

other hand Fromanteel was not a starting inexperienced student, still taking up

a lot of time from Coster to teach all the principles of clockmaking, but immediately a

productive employee.

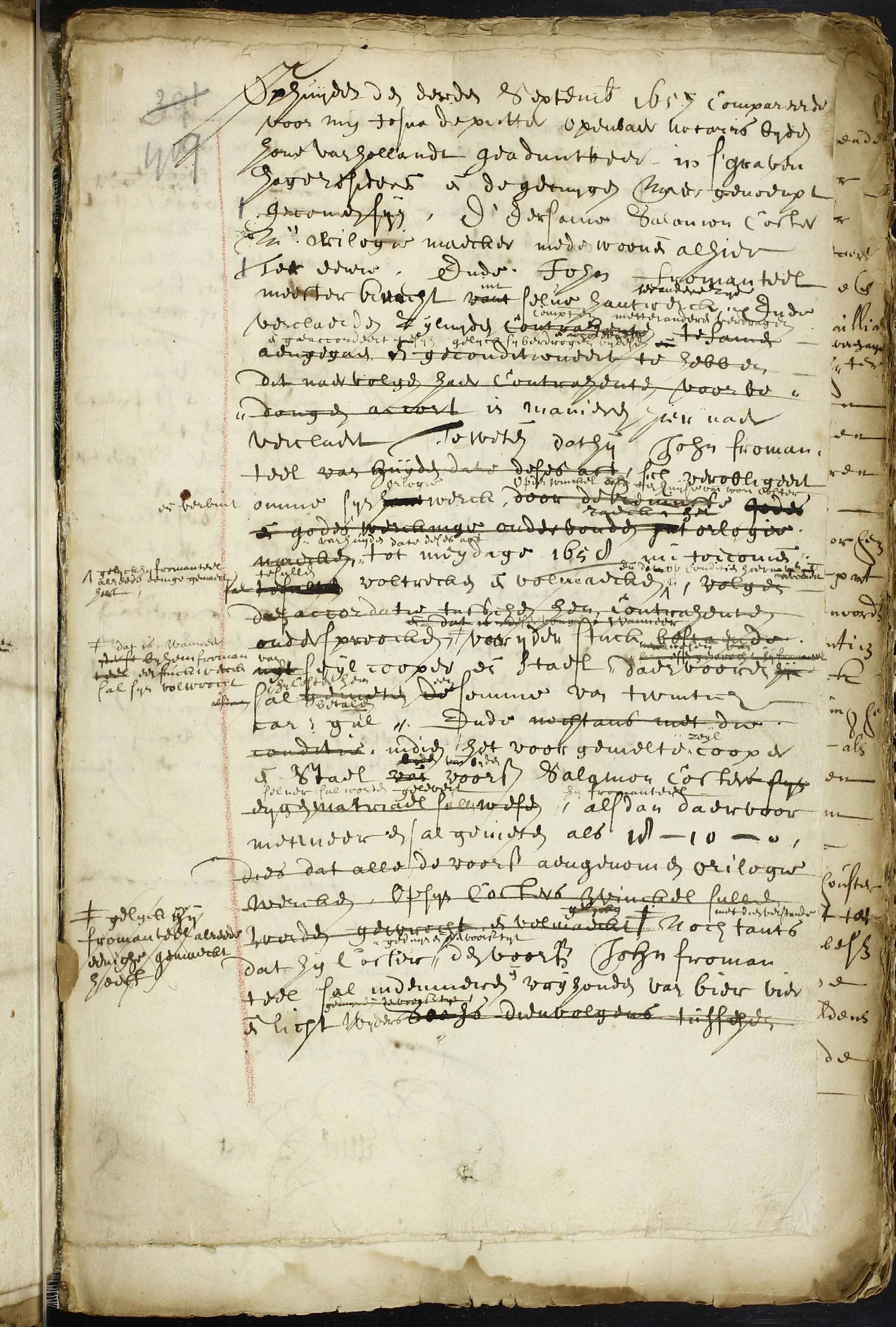

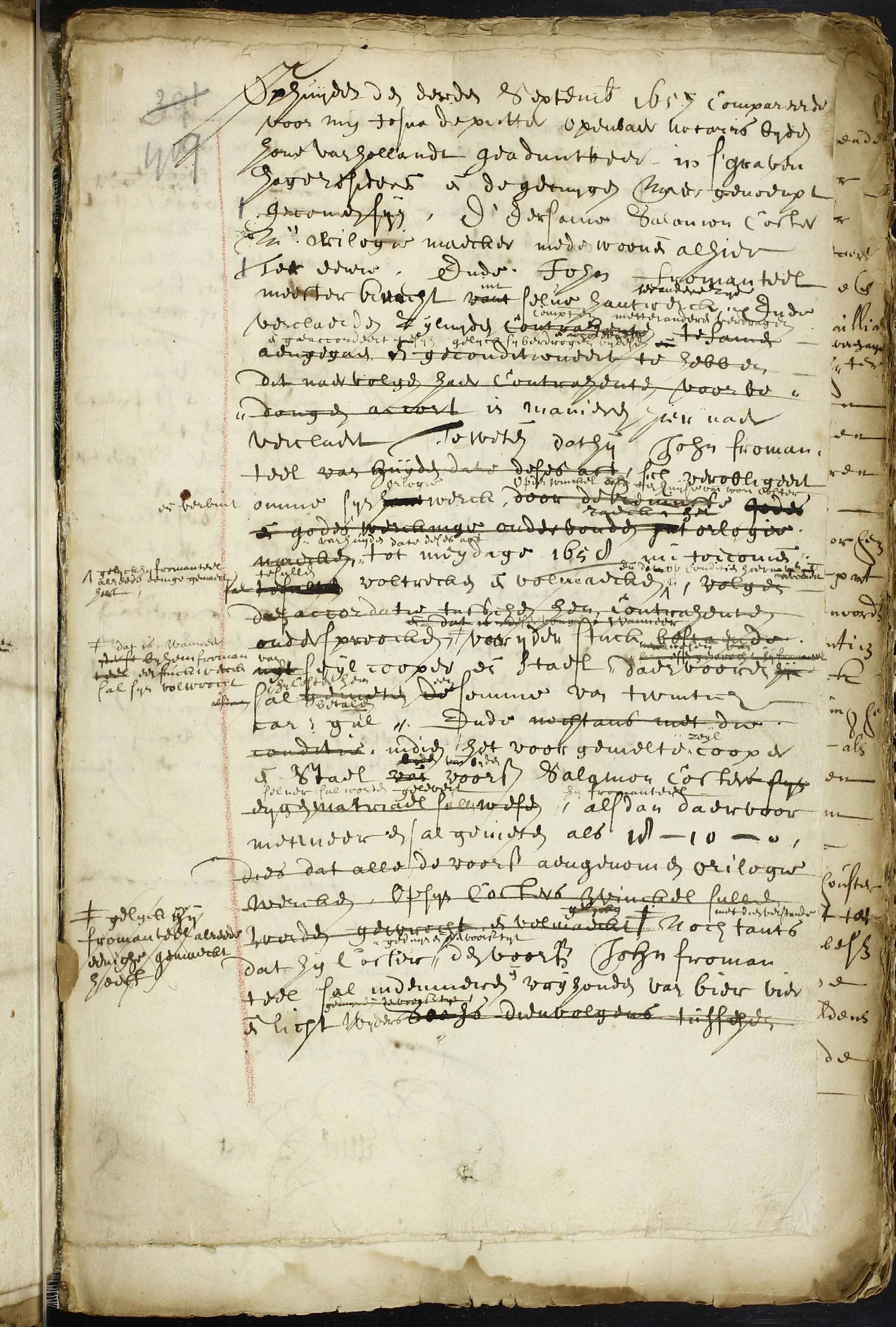

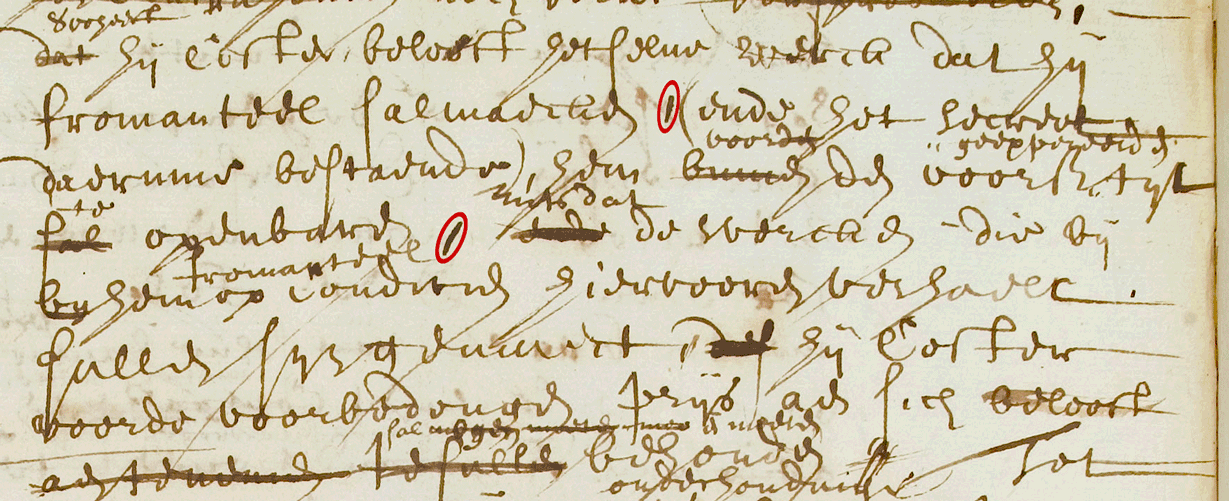

John was hired and in

September 1657 an employment agreement was drawn up for the duration of 8 to 9

months. This agreement, nowadays also known as the

Coster-Fromanteel

contract, has already for decades been a source of the most peculiar

theories.(4

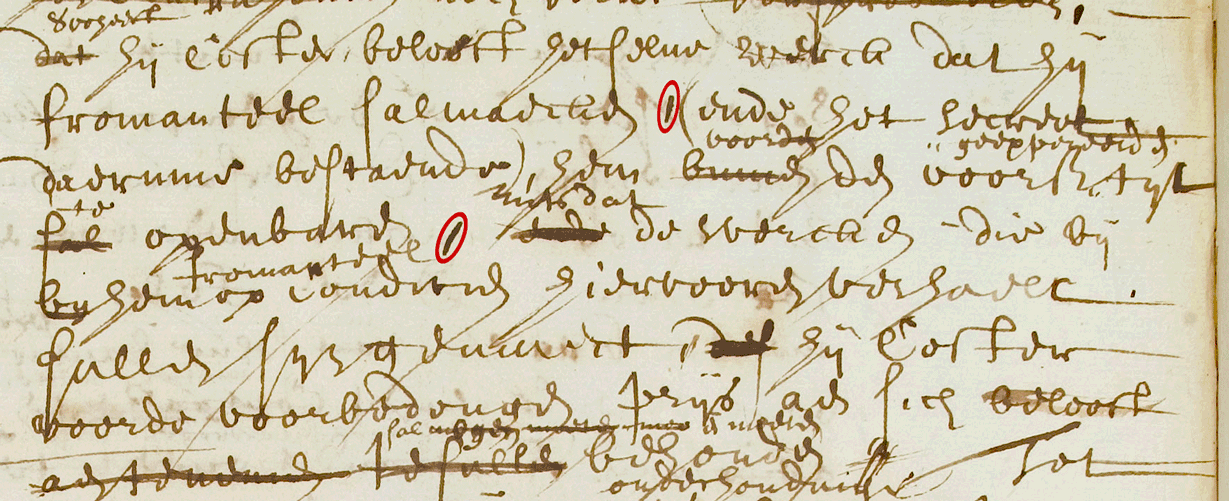

When we look at the facts in

the contract, we see little more than a fixed-term employment agreement with

performance-based pay, between master clockmaker Salomon Coster and skilled

apprentice John Fromanteel.

Fig. 1

The contract

These ‘job titles’ are

historically correct, since Coster has been named as such since 1645 and John

Fromanteel, in the fifth year of his apprenticeship, was still an advanced

student, also according to the rules of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers.

Moreover, these job titles are exactly defined in the employment agreement

between Coster and Fromanteel. The work of skilled apprentice Fromanteel takes

place in the workshop of the master clockmaker Coster and a pay rate per piece

is agreed. On the basis of either the currently still existent Coster pendulum

clocks, or archival documents, it is not possible to determine who did what in

the production process. Even the agreement between Coster and Fromanteel only

mentions the general words "werck" and "orlogiewerck" (i.e.

movement or clock/watch movement), which implicates that any type of movement

could be meant. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that the Coster

workshop had a much larger production than was thought for a long time, and

that also several other clockmakers were working for Coster.(5

Many stories have been

written and thoughts expressed zooming in on the smallest parts (even up till

collet level!). Just the same, we will stay away from these micro level discussions, because

evidence on who did what exactly, can never be delivered.

It would be better to have

the metal and wood of the clocks scientifically examined by experts using the

most modern equipment.

If scientifically proven

authentic, the fact that these are Salomon Coster clocks is evident, just

because the clocks are signed with his name, just as

The Nightwatch was

signed by Rembrandt, being a collaboration of several painters under the wings of

the master. Or a Fromanteel signed clock, on which several clockmakers will

have participated.

Other matters in the agreement,

such as the supply of materials, explaining single phrases, points and commas

in the text, can all be interpreted in various ways, but without additional

irrefutable evidence, they are good for a rainy afternoon discussion, but

scientifically uninteresting.

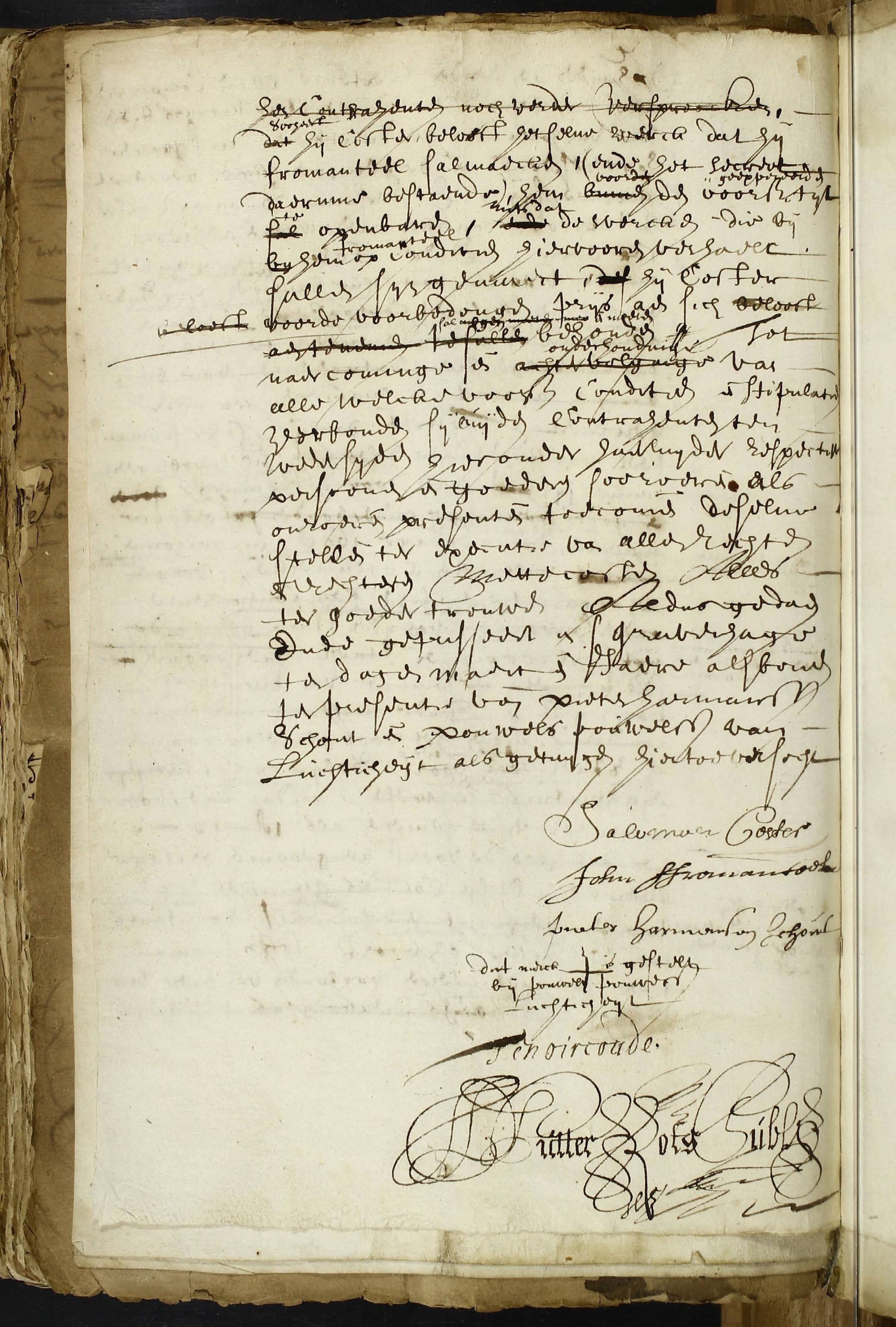

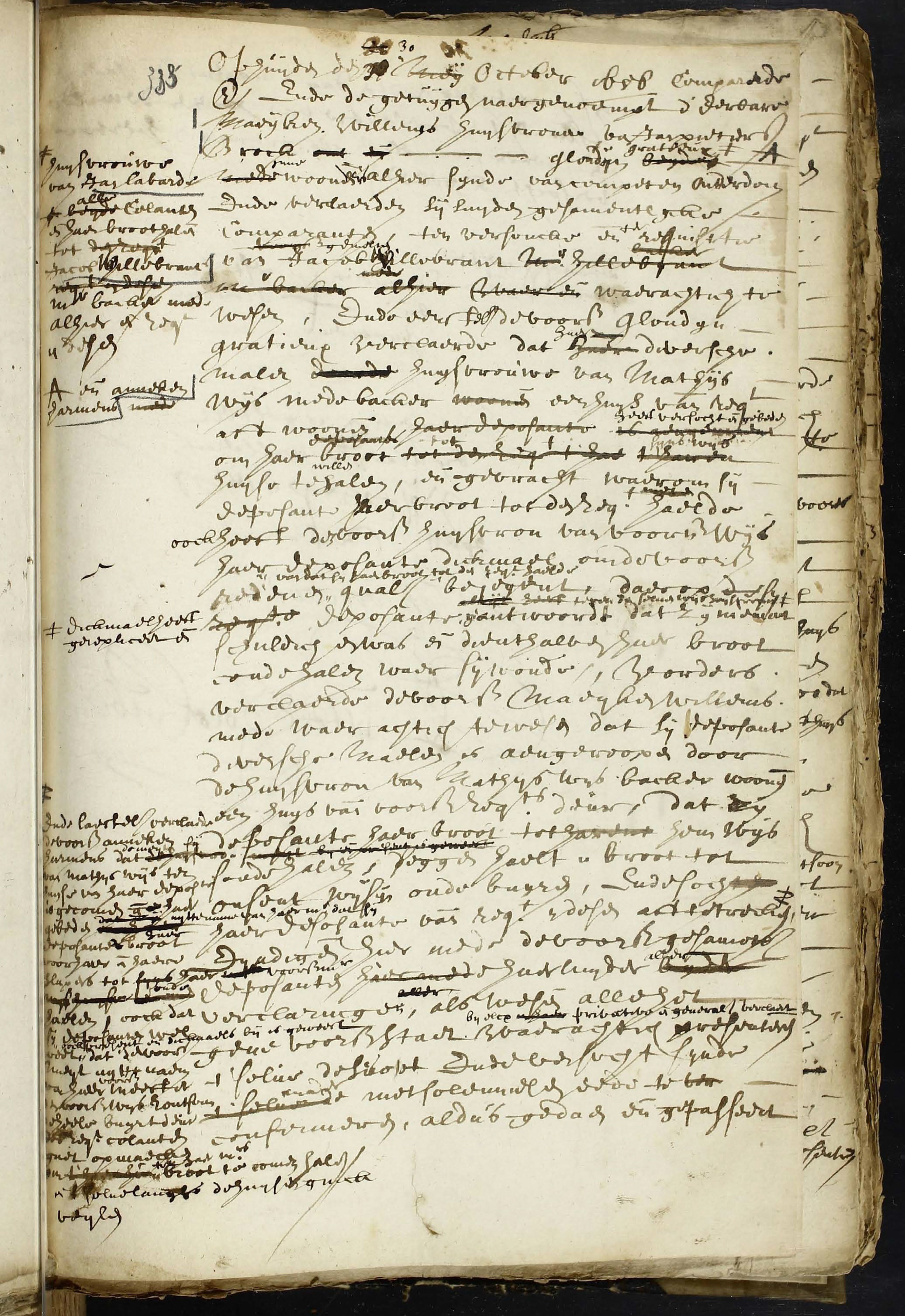

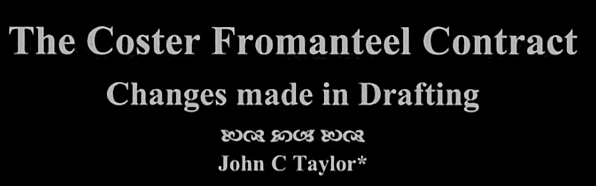

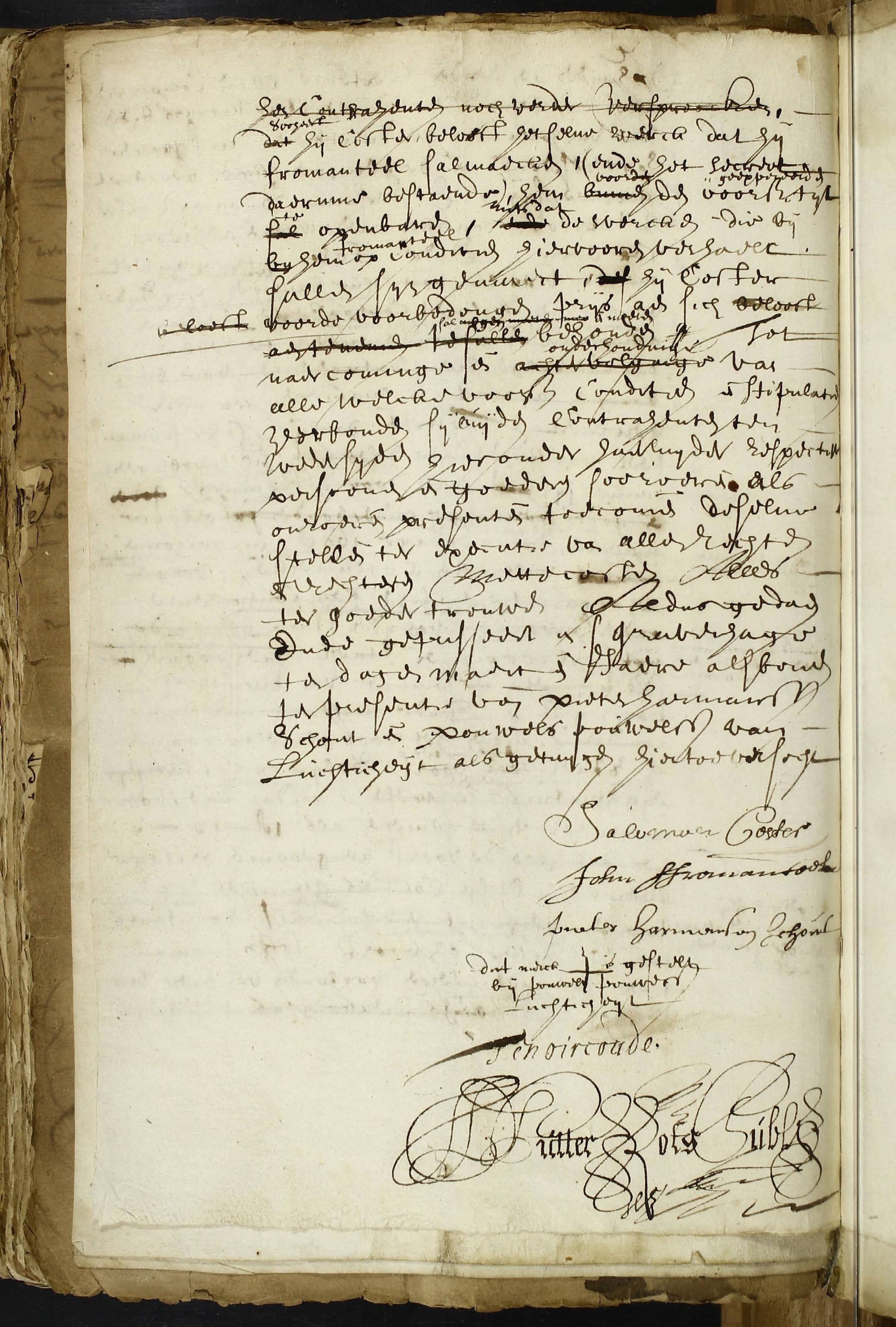

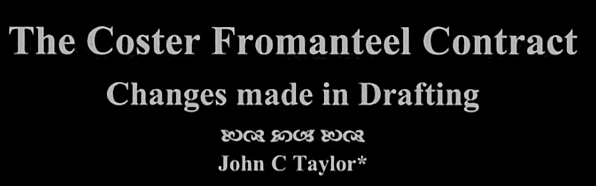

One good example of the lack

of historical knowledge and thorough research in these discussions is the fact

that by some authors a lot of significance and various explanations are

attributed to the numerous erasures in the agreement between Coster and Fromanteel.

fig. 2

Same notary book more erasures

If these authors would simply

study the same notary book, or other 17th century Dutch notarial

protocols, they would see that many deeds contain the same number or even more erasures

(Fig. 2). Unfortunately, this is conveniently overlooked here.

Nevertheless, in the absence

of any important and unambiguous English archives about the first pendulum

clocks, especially our English clock friends for decades now are trying to find

evidence in this contract in favour of Fromanteel in particular.

Whereas previous English

speculations assumed an important role for John Fromanteel in the manufacture

of the first pendulum clocks, Garnier added a new chapter to the

Coster-Fromanteel discussion in the book Innovation & Collaboration.

In chapter 3, Garnier & Hollis try to build a story in which is stated that

apprentice John Fromanteel came to The Hague to explain to master clockmaker

Coster, in eight to nine months, how to make a pendulum clock. At critical

moments, where the reader expects an important archive piece or other

conclusive evidence, remarkably often the words "suggest",

"maybe" and "strongly possible" are used.

Although we stick to archival

documents as much as possible, it sometimes is unavoidable to propose a highly

probable theory. Be that as it may, this theory then must be firmly supported

by facts. When a theory aims to demonstrate a major change in historiography,

the evidence must be strong and conclusive.

As an example: in

Tijdschrift

18/2(6

it is said that the brother of Jannetje Hartloop (Coster's wife) presumably

learned the trade at Coster’s. The proof for this is not conclusive, but it is

plausible. Moreover, and this is important, it is a theory that does not turn

history upside down.

When the attribution of the

first pendulum clocks and the role during the experimental phase is moved from

Coster to Fromanteel, this is of a different order and the evidence must be

strong and supported by multiple archival records.

In their book, Garnier &

Hollis have proclaimed the remarkable theory that Fromanteel taught the making

of a pendulum clock to Coster, instead of the other way around. For this conclusion

they use the following structure:

1.

The weight driven clocks with seconds

indication were the basis of the patent application. Thuret(I was the one

who assisted Huygens in this experimental period and in the first quarter of

1657 was responsible for making the pendulum clocks driven by weights.

2.

In

Horologium (1658) Huygens speaks

about 'manufacturers'. This word is in the plural, so if Thuret assisted

Huygens, there must have been another clockmaker assisting Huygens in this

experimental phase. Who was this other clockmaker?

3.

The Coster-Fromanteel agreement has a

sensational phrase that shows that Fromanteel demonstrates the making of a

pendulum clock to Coster, instead of the other way around.

4.

In addition to Thuret, Fromanteel therefore

was the other one assisting Huygens in the experimental phase of the pendulum

clock. Where Thuret was responsible for the weight driven clocks, Fromanteel

was responsible for the ‘commercial’ spring driven movements.

endsection

In the run-up to Garnier

& Hollis' new discovery in the Coster-Fromanteel agreement (more on this

later in this article) they immediately make a huge mistake. They state that we

should realise that a weight driven clock with a seconds indication was the

basis for the patent application. The main shortcoming is, the patent

application has so far not been found in the archives and the grant of the patent

itself does not mention a weight clock.

End

of this section, click

here to continue.

NOTES NOTES

|

|

|

|

I |

Isaac Thuret ca. 1630 – 1706),

horloger ordinaire du roi,

was one of the most productive makers in Paris in the 2nd half of

the 17th century. He was also the clockmaker responsible for the

maintenance of the machines of the

Académy des Sciences and the

Paris observatory. In 1675, Christiaan Huygens asked the help of Thuret to

produce the first spiral spring watch. In January 1686, Thuret moved

into the ‘Galleries du Louvres’. |

|

II |

‘Ingevolge de bevoegdheid in het Koninklijk Besluit van 23

augustus 1907 Staatsblad no. 237), gegeven aan gemeenten, die aan zekere

voorwaarden voldoen, om de archieven van de notarissen, die hun standplaats

binnen die gemeenten gehad hebben, van het Rijk in bewaring te ontvangen, heeft

de gemeente 's-Gravenhage in november 1910 alle archieven van op haar toenmalig

grondgebied geresideerd hebbende notarissen over de jaren 1597-1811 op haar verzoek

in bruikleen ontvangen.’ |

|

III |

‘sal indemneeren ende vrijhouden van bier, vuur ende licht’

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

Richard Garnier & Leo Hollis, Innovation & Collaboration,

The early development of the pendulum clock in London, Fromanteel Ltd., Isle of

Man, 2018 |

|

2 |

Nationaal Archief, tnr. 3.01.04.01, Staten van Holland, inv.nr. 1611, nr. 22,

d.d. 16-07-1657. |

|

3 |

O.a. in Oeuvres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, Tome

Deuxième, correspondance 1657-1659. p. 108. Nr. 433. |

|

4 |

Haags Gemeentearchief, tnr. 0372-01, Notarieel archief Den Haag, inv.nr. 322,

folio 409. |

|

5 |

Although it was drafted two years later,

the estate statement, drawn up immediately after Salomon Costers' death, shows

that there was a huge stock in the Coster workshop and that Coster also

outsourced work to Severijn Oosterwijck. See: Victor Kersing and Rob

Memel, ‘In de voetsporen van Salomon Coster. Van Hagestraat naar

Wagenstraat’ in: TIJDschrift 18/2. p. 4-9. |

|

6 |

Kersing en Memel, ‘In de voetsporen van Salomon Coster Van Hagestraat naar

Wagenstraat’ in: TIJDschrift 18/2. p. 4-9. |

|

7 |

Translation from

Tijdschrift voor horlogemakers, 1

maart 1903. |

|

8 |

O.a. in

Going Dutch. The invention of the pendulum clock. Proceedings

of a symposium at Teylers Museum, Haarlem, 3 december 2011 Zaandam,

2013). p. 29. |

|

9 |

For more on this topic and Thuret see part

4 of these articles: Part 4: The invention of the pendulum clock – The

Sequel, more inventions. |

|

10 |

Haags Gemeentearchief, tnr. 0372-01, Notarieel archief Den Haag, inv.nr. 322,

folio 409. |

|

11 |

Richard Garnier & Leo Hollis, Innovation & Collaboration,

The early development of the pendulum clock in London, Fromanteel Ltd., Isle of

Man, 2018, pp. 67 |

|

12 |

Richard Garnier & Leo Hollis, Innovation & Collaboration,

The early development of the pendulum clock in London, Fromanteel Ltd., Isle of

Man, 2018, pp. 68 |

|

13 |

John C. Taylor,

The Salomon Coster John Fromanteel contract 3rd

september 1657. Changes made during drafting s.l., s.a.). |

|

14 |

John C. Taylor, The Salomon Coster John Fromanteel contract 3rd

september 1657. Changes made during drafting s.l., s.a.), pp. 2 point E. |

|

15 |

H. Brugmans, ‘Uit de protocollen der Haagsche notarissen’ in:

Die Haghe.

Bijdragen en mededeelingen 1908, p. 1-124; H. Brugmans, ‘Uit de protocollen

der Haagsche notarissen II’ in: Die Haghe. Bijdragen en mededeelingen

1909,

p. 1-78; H. Brugmans, ‘Uit de protocollen der Haagsche notarissen III’ in:

Die

Haghe. Bijdragen en mededeelingen

1910, p. 1-113. |

|

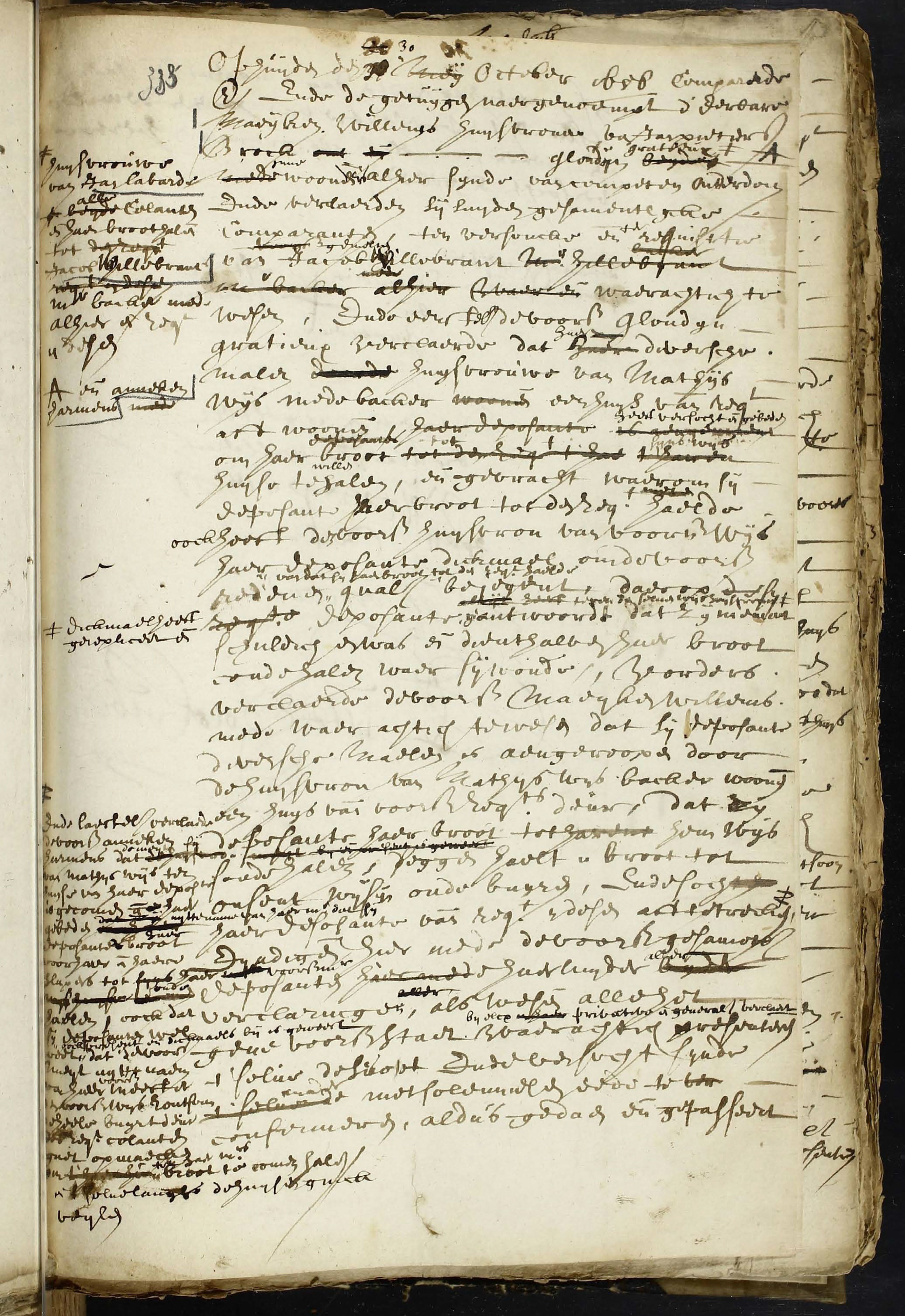

Garnier & Hollis then

draw a wrong conclusion from Horologium (September 1658)(Fig.

3). Huygens

writes in his concluding speech about the uniformity and the firmness of the

pendulum.

Fig 3. Horologium

The translation(7

from Latin is as follows:

‘Much that I could add to this, I leave to

the ingenuity of the manufacturers, who, once they have understood my

invention, can easily find out how it can be applied to the different types of movements

and also to those that have been made according to

the old system’.

Huygens concludes his

Horologium

with the remark that his invention will be further developed and that

manufacturers (among others clockmakers) will accomplish this.

Huygens also states, with the

then current insight, the existing balance/foliot movements are easily

converted to a pendulum. Huygens made this statement more than a year and a

half after his invention, after many pendulum clocks had already been produced.

Garnier & Hollis mistakenly see this as the evidence that several people

were involved during the experimental phase of the pendulum clock (early 1657).

Here the story can actually

stop, but we will take you into some other curious next steps.

Reference is made to a

publication by Sebastian Whitestone stating that Thuret was the clockmaker helping

Huygens with the experimental pendulum clocks in early 1657.

(8

However, Thuret only comes into the picture in the

Oeuvres

Complètes of Huygens from 1662 onwards. Up till now, no document has shown

Huygens knew Thuret before this date, let alone they were working together during

the early phase of the pendulum clock.

Probably, the confusion arose because the editor of

Oeuvres

Complètes, suggests in the margin of a letter from Huygens to Cha<>pelain of

20 August 1659, , Thuret may be meant by the word 'he'.

Unfortunately, the

Oeuvres Complètes do not show the

basis for this suggestion. Nor have we been able to find anything in this

regard elsewhere.do not show the

basis for this suggestion. Nor have we been able to find anything in this

regard elsewhere.

We do know some still existing wall clocks with long pendulum signed

by Thuret.(9

On the basis of various characteristics of both case and movement,

these clocks need to be dated much later than 1657.

_full-bw.jpg)

Fig. 4

Much later than 1657.

Weight driven long pendulum

wall clock by Isaac Thuret á Paris

Garnier & Hollis then return to September 1657 to explain the

new major discovery by quoting the Coster-Fromanteel agreement.

The following

sentence appears in the Coster-Fromanteel contract

soo heeft hij Coster belooft hetselve werck dat hij Fromanteel sal maecken I (ende het secreet daerinne bestaende), hem voor den voorsz. geexpereerden tijt te openbaeren, mits dat de

wercken die bij hem

Fromanteel hem op

conditien hiervooren

verhaelt sullen

sijn

gemaeckt hij Coster voor de voorbedongen prijs aen sich belooft sal

mogen ende moeten behouden.(10

This is translated to:

... Further so has he

Coster promised to reveal the same work that he Fromanteel will make (and the

secret therein existing) to him before the aforementioned expired time,

provided

that the works which by

him Fromanteel on conditions aforementioned will have been made, he Coster for

the stipulated price will be allowed and obliged to keep.(11

Or

in plain English: Coster will tell Fromanteel the secret that is in the

(pendulum) movement and Coster will also take the manufactured movements for

the pre-agreed price.

The

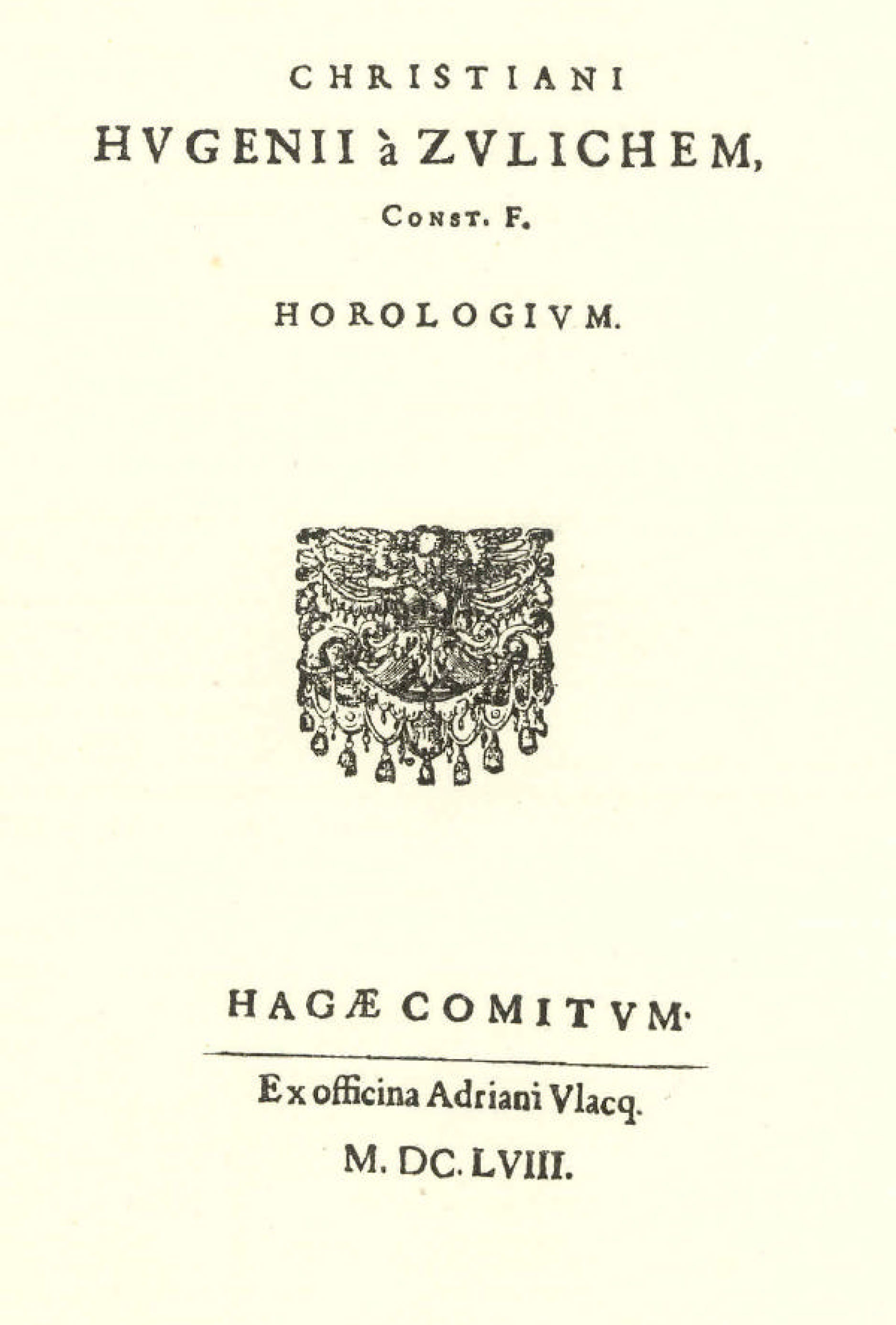

handwriting of notary Josua de Putter is not always clear and his commas and

other punctuation marks sometimes differ. However, Garnier & Hollis see two

punctuation marks as extra parenthesis and the text according to Garnier &

Hollis gets a completely different meaning (Fig.

5). The new sentence now

becomes (see new brackets) as follows:

soo heeft hij Coster belooft hetselve werck dat hij Fromanteel sal maecken

((ende het secreet

daerinne

bestaende), hem voor den voorsz. geexpereerden tijt te openbaeren) mits dat de

wercken die bij hem

Fromanteel op

conditien hiervooren

verhaelt sullen

sijn

gemaeckt hij Coster voor de voorbedongen prijs aen sich belooft sal mogen ende moeten

behouden.

Which then suddenly is

translated to:

... furthermore during the

aforementioned time so has he Coster contracted the same work that he

Fromanteel will make - (and the secret incorporated therein) him to explain

before

the aforementioned expired

time - provided that the works which by him Fromanteel on conditions previously

cited shall be made the same he Coster for the pre-stipulated price to

himself promised will be

allowed and obliged to keep...(12

So we see a larger part of

the sentence in brackets. In this Garnier & Hollis see proof that Coster

did not tell the secret to Fromanteel, but the other way around: Fromanteel taught

Coster how to make a pendulum clock!

Fig. 5

We, and various experts, once

again have looked at the meaning of this new sentence structure and into the

scope of the entire agreement. Unanimously we come to the conclusion that this

new theory, in which punctuation marks are seen as extra brackets, (fig. 5) does not

result in any change in the meaning of the text. In no way it is comprehensible

or possible to follow the conclusions of Garnier & Hollis.

FACT FINDING

FACT FINDING

The tales on the new

Fromanteel story are based on far-fetched assumptions and theories. It actually

entails a recommendation to investigate in the future on the basis of facts

laid down in dated deeds and to take note of the 17th century Dutch

manuscripts, the use of language and the course of events at 17th century

notaries.

Of course one can put forward

ideas and thoughts at certain moments, but when the authors think to have made

great discoveries, as is the case with Innovation & Collaboration, they

will have to come better prepared than bring a theory built on quicksand.

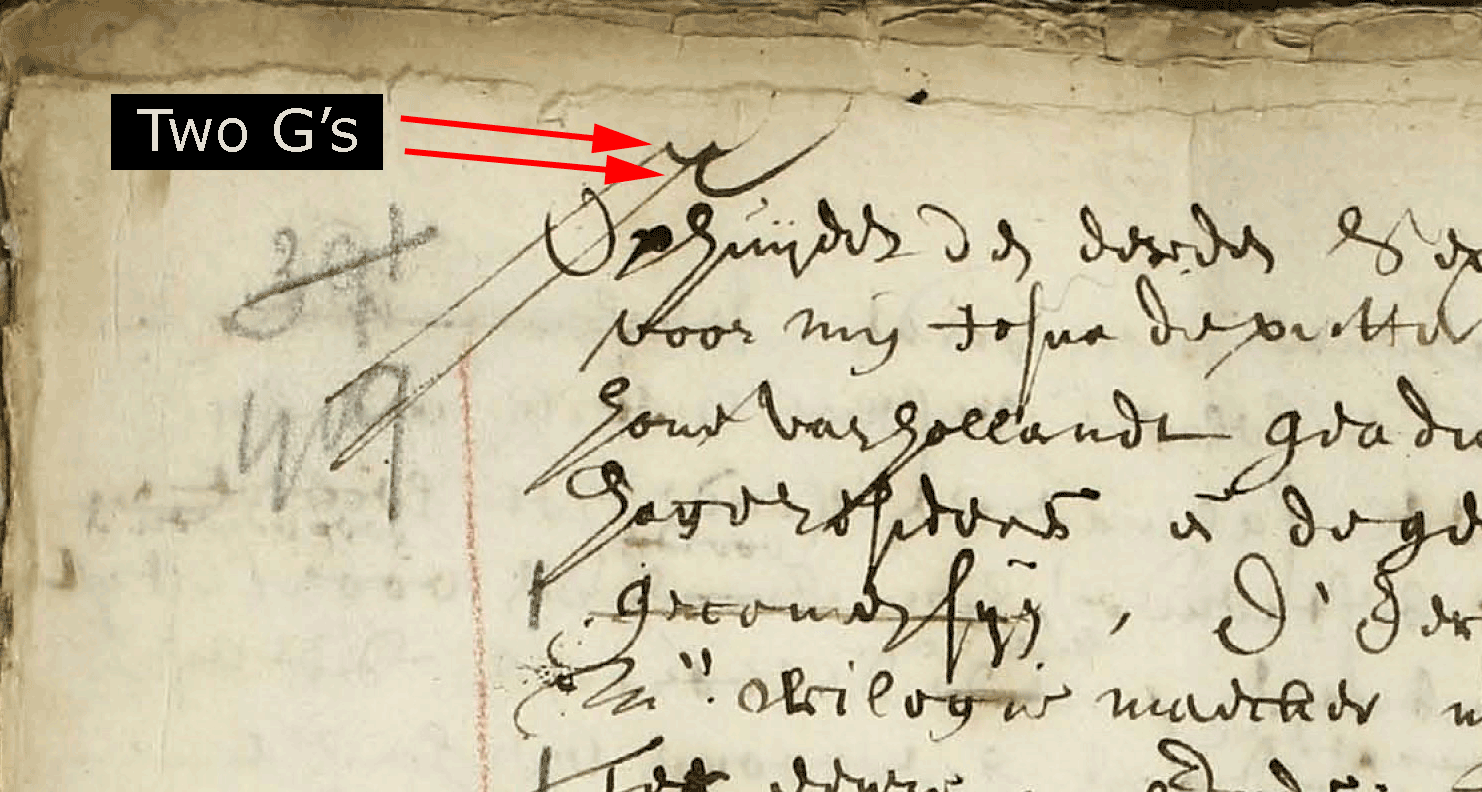

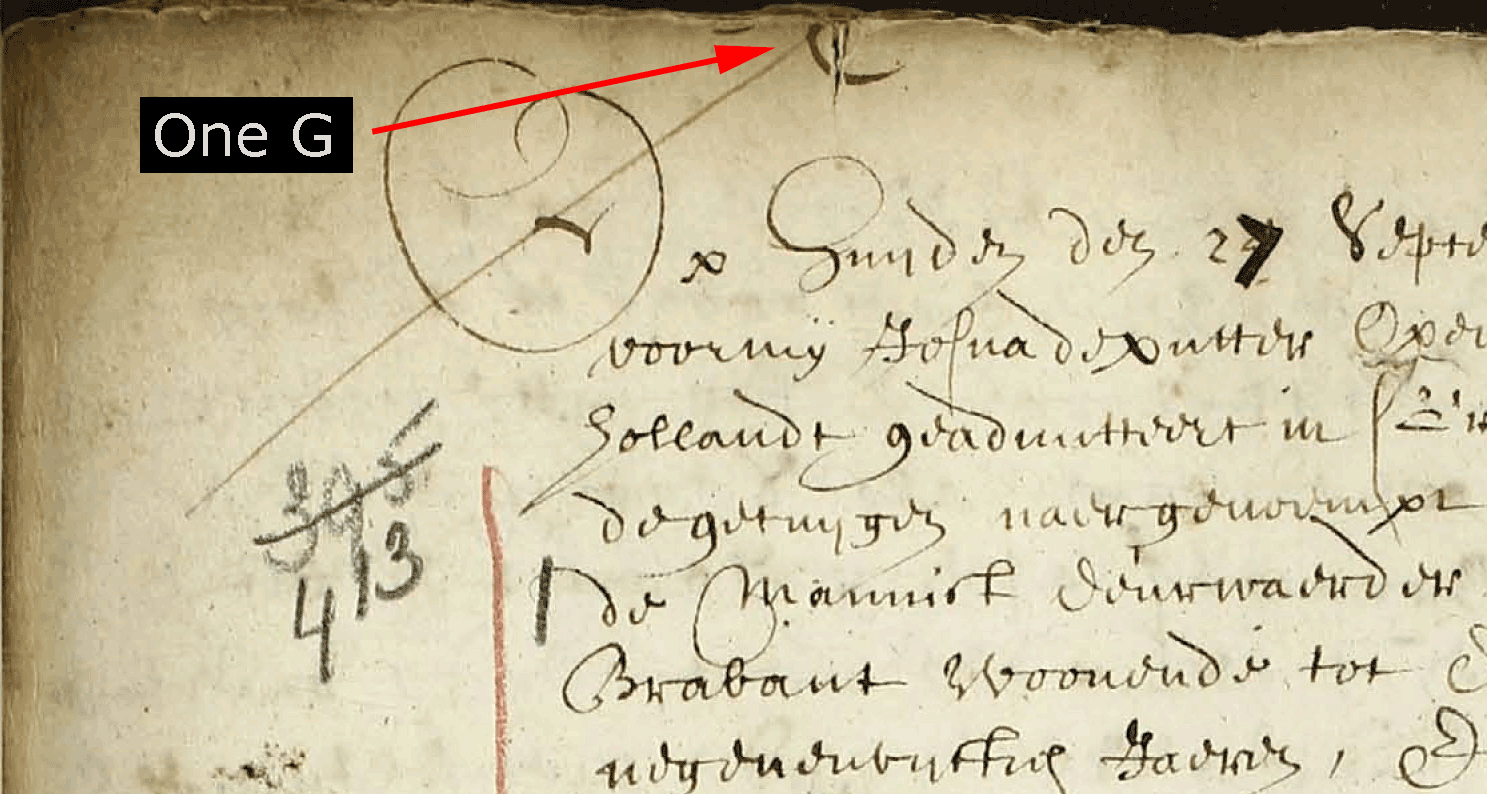

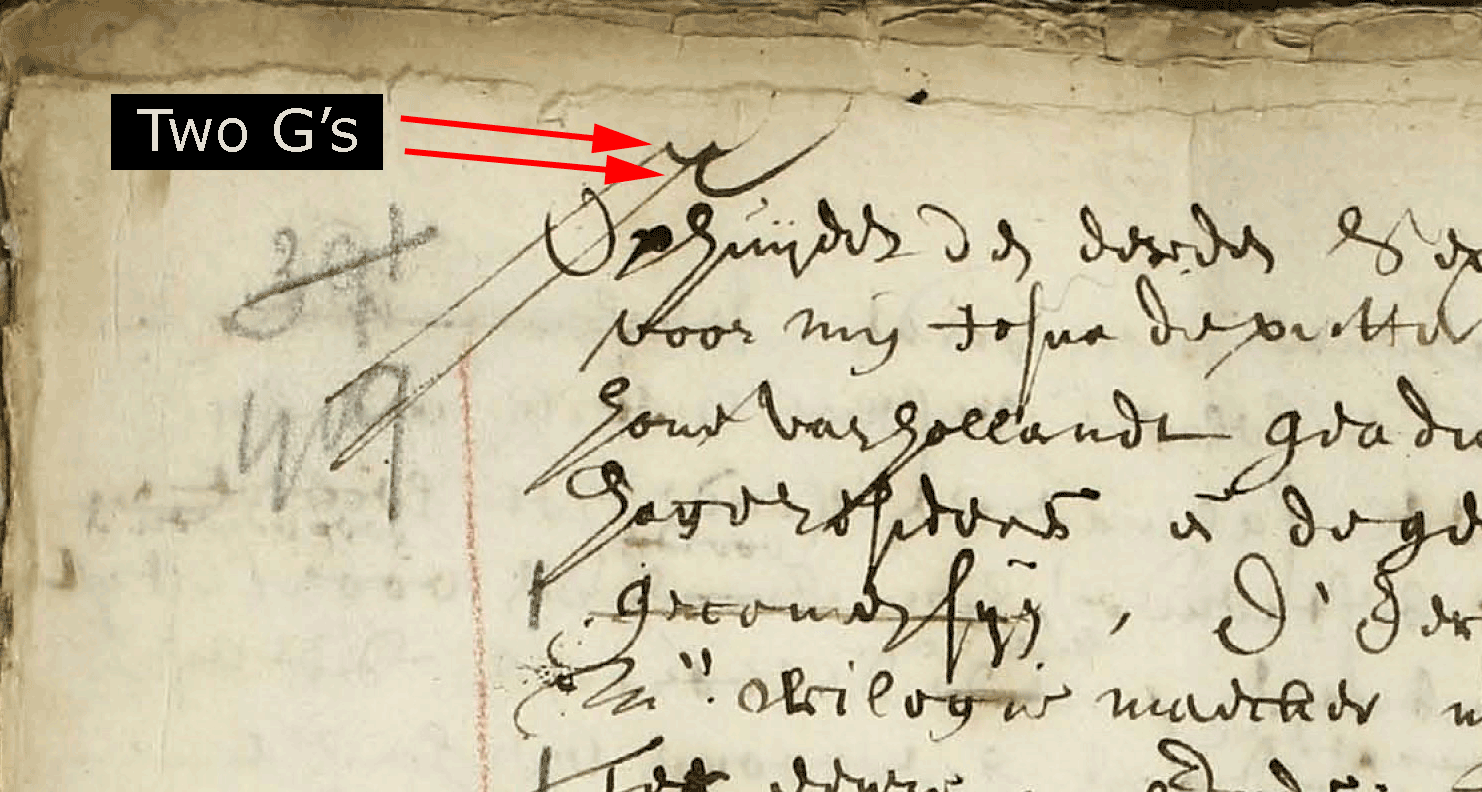

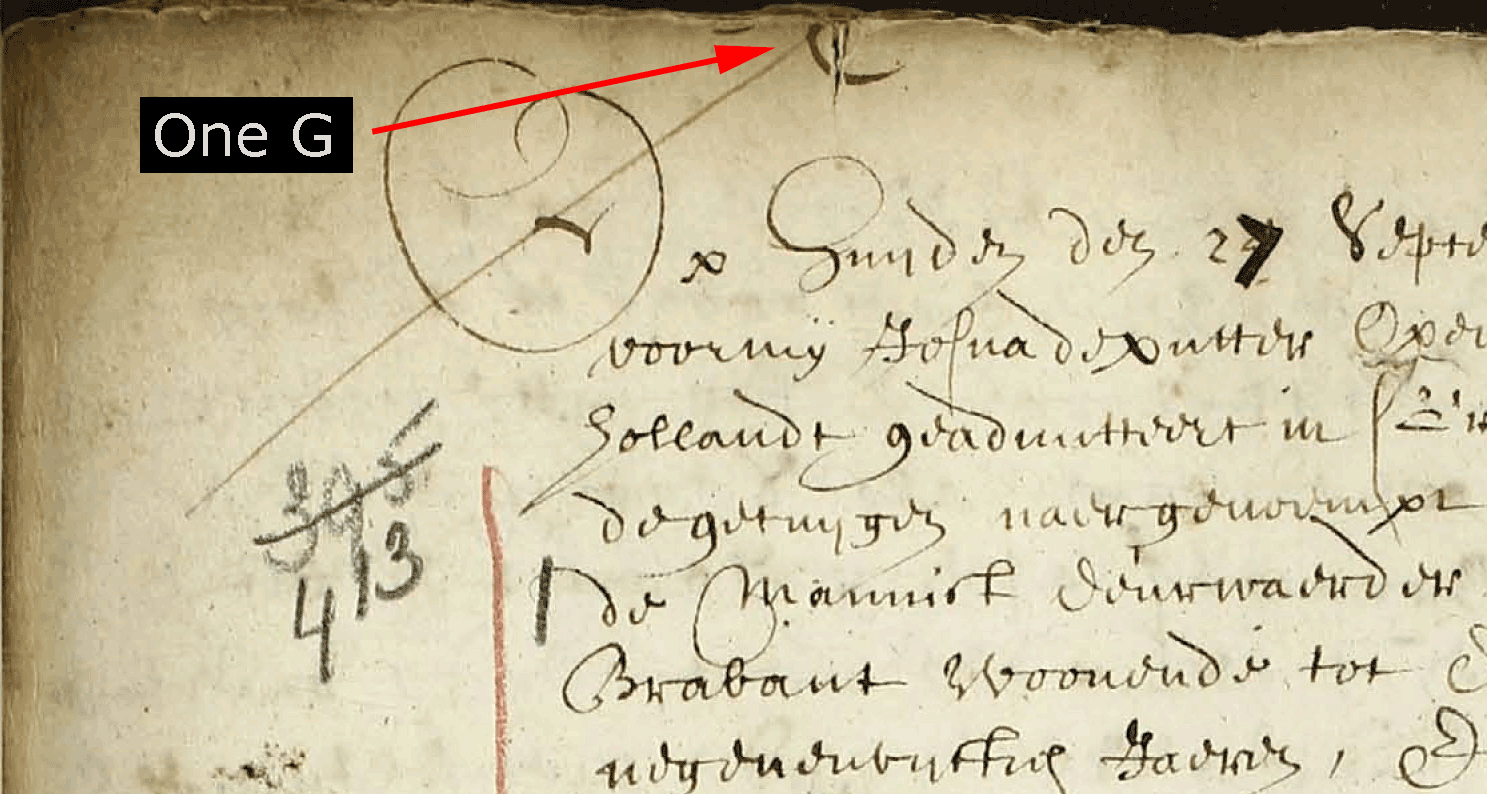

TWO G's

TWO G's

On the occasion of the exhibition

Innovation & Collaboration, Dr. John C. Taylor published and

commented a facsimile edition of the ‘Coster-Fromanteel contract’.(13

The facsimile looks beautiful

and well cared for; clearly, a lot of attention has been paid to this, as well

as to the contents of the contract itself. The document has no less than 67

notes with comments. This enormous number alone already suggests the author is

not accustomed to reading seventeenth-century Dutch notarial protocols, let

alone interpreting them. This is immediately apparent for

paragraph 1]. The author

sees two lines in the top left hand corner, drawn through the original text.

That's right, but they are not just lines or erasures. This are two G's indicating two copies, two

neat copies, have been made of this deed, which may or may not have been

certified by the notary.

fig. 6 Two G's in the top left corner

fig. 7 One G in the top left corner

NOTARIAL

PRACTISE NOTARIAL

PRACTISE

This clarifies point I of the

introduction. Here the author states, according to the authority of Prof. Lisa

Jardin, that no legal system would have such a sloppy document filed.

However, this was common in

17th century Holland. And where were they archived? At the Court

of Holland. After all, this body admitted the notaries in Holland. So the

archives were in custody with the State. And how did they end up at the

municipality of The Hague? We quote from the

introduction of the inventory of the notarial archive in The Hague:

‘Pursuant to the authority

from the Royal Decree of 23 August 1907 (Bulletin of Acts and Decrees no. 237),

given to municipalities, that meet certain conditions, to keep the archives of

the notaries, who have had their place of employment within those

municipalities, from the central government in custody, on November 1910, the

municipality of The Hague received all archives of notaries who had resided at

its territory in the years 1597-1811 at its request on loan.’

(II

This is just an aside, for a

better understanding of the author, who asks himself in note 9 ‘How this

contract can be viewed as draft minutes and where the protocol is stored

remains unclear’. On the contrary, that is as clear as daylight.

Besides, in contrast to nowadays,

notarial deeds were not always drawn up at a chic notary office. Also changes

in the text were not initialled as they are today. A lot of these procedures even

happened in the pub. The world really looked a lot different in the 17th

century.

READING ERRORS

READING ERRORS

Next to mistakes due to lack

of historical knowledge, there are also reading errors. The author is forced to

make use of an English translation, where the danger is that there are

differences in nuance or even differences in meaning. An example: in point K of

the introduction, the author says:

‘The contract does not spell out normal

issues which are taken for granted; for example, the cost of John’s travel to

The Hague is paid by John: Salomon will provide John’s board and lodging. So

why are beer, fire and light mentioned if they were normally supplied by masters

to their workers?’

Indeed, the agreement does

not include things that are normal. But what was normal back then? That really

was not fixed. Subsequently the author claims that Salomon would provide John ‘board

and lodgings’. But that is not what it says. It does only say that Coster

will

‘indemnify and defray Fromanteel (usually to put synonyms in

succession with beer, fire and light’

(III;

so he will provide him with beer, heating and light to be able to do his work.

This also means Coster does not provide him with accommodations and meals. So, Fromanteel

stays/sleeps elsewhere.

HISTORICAL

KNOWLEDGE HISTORICAL

KNOWLEDGE

But there is more, maybe even

more serious. Let us again limit ourselves to some examples, because there are

a lot of mistakes and there is no room to cover everything.

Dr. John C. Taylor, an

entrepreneur and inventor, who has registered more than 400 patents worldwide, states

he has never yet lost a lawsuit about a patent worldwide. Truly a formidable

achievement that certainly commands respect. But this look-and-see statement

suggests that he also has knowledge of patent law and contracts in 17th

century Holland.

This is nothing more than a

suggestion, because apparently he does not have that knowledge. He looks at 17th

century Holland through biased 20th and 21st century

international glasses.

An important example of this

is the introduction of

the

necessary existence of a

Heads of

Agreement.

Quote:

‘Parties coming for a lawyer usually have at

the very least a Heads of Agreement worked out between them, together with a

wish to compromise to some degree to achieve a final Agreement’.(14

That may be customary

nowadays, but was this so in the 17th century? The author states it

is very common - ‘at the very least’ - so he does assume it was so at

the time. In this way he’s working towards a larger role of Fromanteel.

What did the authors want to

achieve with their entire exercise? They wanted to show that a normal agreement

of employment between Coster and Fromanteel is in fact a learning agreement

between Fromanteel and Coster, i.e. a 180 degrees rotation of roles, together

with a change in the value of the agreement itself. In our opinion the authors

have not succeeded.

Too few

arguments have been put forward for this radical change, and at the same time the

authors have disqualified themselves by showing that they have no knowledge of

17th century notarial practice in Holland.

As they are unable to

read archival documents, they for instance would have done themselves and all

readers a favour to have first been informed by Prof.

Dr. Brugmans, Professor of General History.

He more than a century ago published a collection

of 180 work and student agreements from the Hague protocols.

(15 As they are unable to

read archival documents, they for instance would have done themselves and all

readers a favour to have first been informed by Prof.

Dr. Brugmans, Professor of General History.

He more than a century ago published a collection

of 180 work and student agreements from the Hague protocols.

(15

These very quickly show that

the world then did not look as unambiguous and tightly

organised as the authors suggest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

March

2019, Copyright:

(This article is subject to ongoing

revisions.)

LINKS

LINKS

Chr.

Huygens' Œuvres Complètes.

(pdf)

Coster

Fromanteel contract.

Archive research on Salomon Coster.

Chr.

Huygens

Horologium 1658.

(pdf)

|

_full-bw.jpg)

As they are unable to

read archival documents, they for instance would have done themselves and all

readers a favour to have first been informed by Prof.

As they are unable to

read archival documents, they for instance would have done themselves and all

readers a favour to have first been informed by Prof.