|

A Royal

'HAAGSE KLOK'

by: Keith Piggott. |

|

|

|

APPENDIX

3

Back to Main Document. APPENDIX

3

Back to Main Document. |

| |

|

●

Open Research Project on Early Pendulum Clocks. |

|

|

Researchers will now be able to add to present knowledge, by

comparing images and dimensions of the subject Oosterwijck with Coster’s known

Hague clocks, also with comparable European pendulum clocks. I recommend the

following pointers to horologists and researchers, as being probably rewarding

new lines of enquiry.

Salomon Coster’s pendulums fall into the earliest phase of Hague clocks. His

known pendulum timeline is from his June 16th 1657 Patent, assigned to him by

Huygens for 21 years, to his decease in December 1660. Of course he had to be

involved even earlier in Huygens’ initial trials and preparing Patent

Applications.

In Coster’s pendulum oeuvre, time-pieces having ‘square’ pillars are regarded as

the earliest of his few extant clocks. all being attributed to John Fromanteel

under his Contract with Coster on September 3rd 1657. Clocks having ‘round’

pillars are thought to be later. As a consequence of this rather uncertain

methods of dating, Dr.Plomp’s chronology puts Coster’s earliest extant timepiece

D1 bearing scratched date 1657, among his post-Contract Oeuvre. Whereas,

Huygens' earliest drawing of his 1657 weight regulator, (I assign it reference,

'DØ1W'), shows baluster pillars.

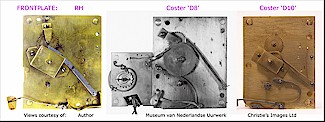

fig. OR1 (click to enlarge)

The Box Cases of the 'Royal' and three Coster Hague Clocks.

Extant timepieces, alarums and striking clocks, attributed to Coster, all have

four-wheel trains; all have plain unsigned movements; all have four pillars, all

riveted to the front plate and pinned at the back plate. All his single and

split-barrels are front wound. All have round dial-feet, except D5 (square), D8

(hexagonal). Timepieces have set-up ratchets mounted on front plates, his Alarum

'D5' has the ratchet on the backplate, whereas his striking clocks have internal

set-up ratchets now on the front barrel cap (like Oosterwijck's). Coster’s

‘going’ trains all have the first wheel planted behind the barrel; centre

pinions fix centre wheels; all have vertical trains to the 3-spoked contrate and

verge-escape wheels; all have short verge-staffs held in Dutch block-potences;

and naturally, all had Huygens’ patent crutched-verge with his suspended

pendulum and cheeks (several are reconstructed).

Immediately one questions, why did Oosterwijck plant his centre-wheel at the

front? And why did Pierre Saude too, in 1659, when Coster purportedly had set

the only model used by the French makers? (see “Huygens Legacy”, Nr.14,

pp.40-41).

Why the paucity of extant pendulums made by Coster himself? Coster? 'D3', found

incomplete in France, by Gerd Wijnen, has an unconventional barrel cap, fitted

into its barrel by a curious dovetail; it then had a tear-drop pierced,

sculpted, hour hand of an earlier type. Berry Van Lieshout suggests this method

of fixing the barrel cap might relate to Coster’s apprenticeship using

Renaissance techniques. Privately, he suggests it could well be the only true

‘Coster-Coster’ pendulum extant. Yet its square pillars place it, too, within

the Contract period, as that single feature is attributed solely to John

Fromanteel. Less obvious autograph features are being ignored; we must identify

and qualify all these too.

Fromanteel’s signed and dated 1658 timepiece looks like Coster’s. However, its

six square pillars are riveted to a taller back plate, pinned at the front; its

set-up ratchet is on the back plate; its watch-stop work is on the going barrel

at the front cap, having a five-wheel train, planted vertically, with an

intermediate wheel (for longer duration) fixed to its arbor by a pinion at the

back plate (like Coster centre-wheels), with its centre wheel reversed to the

front plate, to the now rebuilt Dutch potence block; having Huygens’ horizontal

escapement and his suspended pendulum.

Bartram’s little clock c.1659, has four tapered square pillars, pinned at the

back plate, now with two five wheel trains; the centre wheel at front plate;

having two back-wound going-barrels in place of a split-barrel, each has

diminutive watch-stop work set on the winding squares at the back plate; now

with a pivoted pendulum (but signs of a Dutch escapement). His going wheels all

have three spokes, typical of the Hague clocks. [Bartram’s relationship

with Fromanteel is presumed; Livery Company records show that in 1655 Simon

Bartram, Thomas Loomes and John Fromanteel were all Sureties to Ahasuerus

Fromanteel; this probably refers to the younger son, (apprenticed to Lionel Wyth

on 21 June 1654, whom Bartram had taken over during his apprenticeship), who was

made Freeman on 6th July 1663].

Edward East made several early spring-driven wall clocks with beautiful large

dials, all-over florally engraved in his goldsmith trained free style, all

having Fromanteel's pivoted pendulum, a single hand, some with alarum, and all

having the strike on a second barrel. One movement was exhibited at Octrooi op

de Tijd, nr.40, (Museum Boerhaave, 1979; reproduced in Early English Clocks,

plates 104-107). Originally it would have had an ebony Tabernacle case, like his

'Huddleston' clock (Lloyd, H A, 'Old Clocks'. plate 15c). East also made a small

box-cased timepiece, having early four-wheel train, now restored with verge

across the plates to a pivoted pendulum in the manner of Fromanteel. Its centre

wheel is at the front plate, its ratchets too. The signed backblate inscribed

with a spurious date 1763. East's bold baluster pillars are unlike other London

or Hague pendulum clocks, but are seen in Bernard van Stryp's contemporary

Antwerp clock. East's going-barrel extends in four protruding lugs, with holes

by which the front cap is pinned. It is unconventional, but also seen on the

anonymous nodding-Chronos posted clock, (formerly Ilbert’s, now in the British

Museum), which -on other grounds- I have likened to Davis Mell’s musical

automaton chamber clock, I have attributed both those clocks to Ahasuerus

Fromanteel Senior.

Are these Fromanteel, Bartram and East pendulum movements just the distant

English cousins, or the natural brothers, of the Royal Oosterwijck?

What is certain but is usually overlooked, in 1657 and later, any English

pendulum construction that mirrored the Dutch spring clock format, whether made

by the Fromanteels, Bartram or East, had to be derived directly from an actual

Coster clock in hand, i.e., not from Huygens’ intentionally diverting "OP"

drawing of a half-seconds weight clock that he published first in “Horologium”,

(September 1658). Huygens' original seconds' weight clock, presented in Coster's

June 1657 Patent, was not published until "Horologium Oscillatorium" in 1673.

Severijn Oosterwijck's Royal clock proves that, during 1657-8, he was close to

Salomon Coster and John Fromanteel then in Coster’s employ, as well as having

Huygens' confidence. The fact that his clock bears his own signature indicates

he nevertheless remained independent and had his own clientelle. We also know,

in May 1660, Alexander Bruce (Earl of Kincardine) joined Charles II in The Hague

for His triumphant return into England. It is likely that Huygens' new pendulum

clocks figured in their discourses, leading to their contacts with Huygens and

Oosterwijck, also arousing Bruce's subsequent interest in the pendulum's,

supposed, Longitude applications, which he independently was to pursue on his

return to London; very probably using the Fromanteels to develop his "F" forked

crutch which he first showed to Huygens in London during 1661.

However, we do not know when Severijn first had contact with the Fromanteels'

workshop in London. Did he, like John Hilderson and the Roussels, make that

short sea crossing somewhat earlier? If he did not, then similarities between

his clock and Fromanteel’s early practices are even more remarkable. However, if

he did have earlier contact, that might resolve the secret of the September 3rd

1657 Contract, between young John Fromanteel and prosperous Salomon Coster – who

curiously pledged his entire, present and future, wealth to meet its arcane

terms.

A catalogue raisonne´ of Severijn Oosterwijck’s Oeuvre would be invaluable.

Several are identified by Dr.Plomp, Mr.Vehmeyer, and “Huygens’ Legacy". The

“Lieberge” silver-mounted timepiece-alarum is another of Severijn’s early gems,

ascribed to 1658-1662, it sets new heights in precious ostentation.

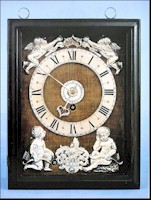

Fig. 3a1 (click to enlarge)

Oosterwijck's exquiste, silver-mounted, 'Lieberge' Hague clock. (Images courtesy

of Sothebys Amsterdam).

Lieberge's cheek cocks are like the subject clock, but its

reversed verge-cock resembles Coster's. It is an early example of a Hague clock

being signed on the backplate, and it introduces his trademark plate outlines.

(Sotheby’s Amsterdam, 21-02-1995, Lot.324). Two later Oosterwijck clocks, one

also signed on the backplate, are depicted by Dr.Plomp, ("Pendulums", Op.Cit.

nrs.84, 85).

|

|

|

|

Links to

Open Research matrices on early pendulum clocks:

●

Go to 'spring driven' clocks.

●

Go to 'weight driven' clocks.

|

|

|

There is so much to be learned, so much evidence to be revisited, the task

should impassion new researchers to take up the mantle from we gracefully

ageing enthusiasts. To start the

ball rolling, I offer an open research Matrix in the Horological

Foundation’s court.

|

|

| Click

here to contribute to the project |

|

|

More

project documents:

●

Memorandum D4

(Courtesy Science Museum)

|

|

|

It was not usual for the earliest Dutch pendulum clocks to have signed

backplates; however it may now be assumed that Oosterwijck did by 1662. (I

discount the dated dedication on one regulator). Brigadier Meyrick Neilson of

Tetbury once had an Oosterwijck table clock, having an English dialplate and

olivewood case, having an offset-winder for a fusee, signed 'Severyn Oosterwyck

Hague' on the wedge-shaped backplate. Leopold and Weston made a connection with

the longitude experiments, (Weston, A.,"A Reassessment of the Clocks of John

Hilderson", Antiquarian Horology, Vol.24, Nr.4, pp.407-432, June 2000, AHS).

Probably it is the earliest Hague clock to have a fusee*, being good evidence of

the London origin of Bruce's original sea-clock he showed Huygens in 1661. The

seven-inch pendulum (Huygens says 9 inches) oscillated at around 142

beats/minute, a peculiar number if he intended to show Seconds'. Its rear dial

indicates 4-minutes, being 1 degree of latitude, but not yet

understood. Pilot-mariner Brian Walton points out, the Babylonian astronomers

divided 24 unequal hours by 360 degrees, using the product 4 minutes "Ush" as a

unit to calculate eclipses. He also notes, 4-minutes is the sidereal variation

with the mean day - (mean time variation is 3m 59s); useful for taking star

sightings without needing solar equation tables. On land, sideral time might

also be used to rate the timepiece, or to take star sightings to fix longitude

at ports of departure. I have enlightened the extant clock's custodian. [* I do

not discount Coster's earlier use of Fusee in his early pendulum oeuvre; a hard

habit to break].

Early pendulum Longitude Clocks, the first by Scotland's Alexander Bruce, then

by Holland's Christiaan Huygens, involved Severijn Osterwijck directly, from

1662 to 1664. Longitude timekeeping was of huge import, but little is known of

the actual clocks. As I have postulated before, and repeated herein above, I

suspect that Simon Douw of Rotterdam intended his patented 1658 clock for Marine

Longitude, for which its spring remontoir and beam-oscillator (crossbeat?) were

ideally suited; a paradigm that Huygens did not then appreciate, neither in

mischevious 1658 litigation, nor in wasted years using pendulums and weight

remontoirs – to Robert Hooke’s amusement and lecture note animadversions, (see

British Museum MSS -Sloane 1039, folio 129). During contested litigation in

1658, Douw very wisely kept counsel about any intended maritime application -

for his home port of Rotterdam - he died in Sept.1663.

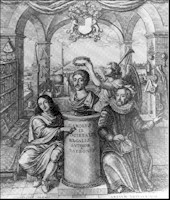

Like Weston, I draw attention to the frontispiece to Thomas Spratt’s ‘History of

the Royal Society of London’ (1667), engraved by Wenceslaus Hollar to John

Evelyn’s design, depicting the founding of the Royal Society which had been

mooted by Sir Robert Moray. Horological items include, probably Bruce's

Longitude Clock, also a curious Tall Clock, possiby the Bishop of Exeter

Dr.Ward's 'Lawrence Rooke' commemorative clock by Ahasuerus Fromanteel in 1662-3

given to the fledgling Royal Society.

fig. 3a3 (click to enlarge)

Hollar's 1667 Frontispiece to Spratt's 'History of the Royal Society'.

A garlanded bust of King Charles II stands upon a pedestal

between Viscount William Brouncker, the first president, and Francis Bacon,

Viscount St.Alban, surrounded by the regalia also its members’ scientific

accoutrements. Of interest, and confirming Hollar's attention to detail, is

Robert Hooke's pole-telescope, Robert Boyle’s famous Torricellian apparatus,

also a small triangular clock hanging from the wall, apparently on Cardan’s

suspension.

Hooke's telescope is also a reminder of Lawrence Rooke (1622-1662) who had

championed Longitude timekeeping, but by the Lunar Observation method treating

the moon's irregular surface as gnomons on a sundial, (to compare a first

magnitude star's altitude against a known origin at the same time), Charles II

was his convert. (see Lomas, Dr.Robert, "Sir Robert Moray,

Soldier,Scientist,Spy,Freemason and Founder of The Royal Society", Gresham

Lecture, 4th April, 2007). Rooke's untimely death, perhaps, was fortuitous for

the better advancement of determining Longitude by mechanical clocks. The

conflict of these two opposed schools of thought persisted lhrough the 18th

century, even setting astronomer Maskelyne against Harrison who won.

The triangular clock in Hollar's print, probably, is Alexander Bruce’s first

Longitude clock he showed to Christiaan Huygens in London in 1661. It raises the

vexed question, "Who made it for Bruce?"

Whilst in the Hague, from March to December 1662, Bruce had two similar clocks

made by Severijn Oosterwijck*; antedating Huygens’ own rectangular weight-driven

Longitude designs with weight remontoirs. During Bruce's return voyage to

England one of his Oosterwijck clocks was badly damaged, John Hilderson in

London was engaged to make a copy, which was used in Capt. Holmes' subsequent

voyage to The Gambia in 1663-1664. [* Leopold, J.H., ‘The Longitude

Timekeepers of Christiaan Huygens’, (‘The Quest for Longitude’, p.104, n.21,

edited by William J H Andrews, Harvard 1997)]. As a result of this paper, might

one of Oosterwijck's Longitude-clocks be found?

Of note, too, Hollar's print also depicts a Palladian window balcony, with a

curious tall case clock having a small square dial surmounted by a pyramid

obelisk, unlike any surviving English clock. Might this represent Dr Ward’s

"large pendulum clock" of Birch's 1756 history, the one made by Fromanteel?

Without its obelisk, it would resemble Fromanteel's long duration Kingwood

longcase clock now in the British Museum; its position, as shown, would also

resolve the rear-doors to the trunk of that clock. (see Dawson,Drover,Parkes,

’Early English Clocks’, Chap.XI, p.501 and pl.742-743, ACC 1982). If the clock

shown had a long-pendulum, probably it had Huygens' OP gear with a vertical

escapement, and beat seconds and a quarter, or longer; already long used by

astronomers; when its extra-long pendulum might be suspended above the movement

at the obelisk’s apex, the pendulum bob oscillating within the plinth, impulsed

by an extended crutch, (like later Zaanse and Friesland clocks).

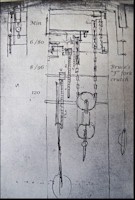

Christiaan Huygens' well known early drawings of sea clocks, inspired by

Bruce's, but having his later patented weight remontoir, are depicted as weight

clocks; whereas the spring barrel with fusee had to be the preferred motive

power - as Robert Hooke and Ahasuerus Fromanteel realised. Was it then

Fromanteel who had made Bruce's prototype, to Hooke's specification? Was Huygens

disingenuous, again, in depicting his trial Longitude clock on a weight, simply

to divert potential competitors?

Huygens' declared "nine-inch pendulum" would not indicate Seconds' directly, but

his first remontoire sketch, at Leiden, shows a four-wheel train having a

Seconds' hand, the Greatwheel (120), the Centre (8/96), the Third (6/80), the

vertical Escape shown as "6/min" (sketch shows 8 escape teeth visible, 17 teeth

would give 120.89 beats). Huygens' train in no way resembles the

Oosterwijck-Bruce Longitude fusee movement which I am presently constrained from

publishing. By such fugitive clues we advance our knowledge of this vibrant

horological period.

Fig. 3a4

(click to enlarge)

Huygens' first sketch of his Longitude clock and weight remontoir. (Huygens'

Oeuvres, MS Aug-Sep 1662, Acknowledment to University of Leiden).

After conducting this unexpectedly consuming and even

self-indulgent review, the subject rewards itself, I now suspect that

Oosterwijck’s prior involvement with the Fromanteels is not unlikely. But,

having once crossed swords with ‘professional’ antiquarians that led to an

invitation from the Horological Foundation and my first published paper in 2005,

here I shall let loose the reins, in the hope of widening the pool of

enthusiasts who will delve into the still murky waters of the early pendulum

story, then contribute their knowledge. Historians and researchers are not

helped by possessiveness of some custodians who should realise the merit in

'open research' to assemble the facts that may determine evolutions and

chronologies, ultimately to benefit scholarship. I commend the example of Museum

van het Nederlandse Uurwerk (Museum of the Dutch Clock), who alone keep records

of trains and are most helpful to any research.

There is so much to be re-learned, and so much evidence to be re-visited, the

task should impassion new researchers to take up the mantle from we gracefully

ageing enthusiasts. To start the ball rolling I offer a simplified version of an

open research matrix being assembled on the Horological Foundation website. I

recommend it to all.

|

|

COMPARISON

TABLE

Click

here to see data of this clock and other early pendulum clocks in the 'Open

Research'

comparison table.

|

|

|

Copyright:

R.K.Piggott,

February 20, 2009. Copyright:

R.K.Piggott,

February 20, 2009. |

|