|

This page is under construction.

A Royal

'HAAGSE KLOK'

Severijn Oosterwijck

Haghe met privilege

Table of contents:

Type Ctrl+F to find any word on this page.

•

INTRODUCTION.

•

Huygens' authorities.

Huygens'Pendulums

Collections and Exhibitions

DidacticScholarship

Who was Severijn Oosterwijck.

•

General observations.

The Inspection

Originality

Unique

Features.

Plomp's

Charateristics Properties

Comparables

•

PART I

HOROLOGIUM

The Clock

The velvet fronted brass dial plate.

Signature Plate

Chapter Ring

Coster Hands

Dial Latch

Pendulum Holdfast

(Type Ctrl+F to find any word on this page)

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Severijn

Oosterwijck’s, earliest known, spring-driven pendulum clock was first

published by clockmaker-restorer Paul Shrouder Hon.FBHI, ("A Mantle Clock", Horological Journal, BHI, Sept. 2008). He recorded

his restoration and alluded to its history. I recognised its real

significance and contacted the BHI. Subsequently, at Mr. Shrouder’s

workshop, I met the owner with his rare Hague-Clock (NL.Haagseklok).

First I established there were no commercial interests to serve, only

horological and historical ones. I was told that, by family tradition,

cited in Wills, and by descent, this little Hague clock has been in

their family since its gift to their ancestor, with a Knighthood, from

Charles the Second on His Accession to the Crown in June 1660, in

gratitude for financial support in exile during the long interregnum

(1649-1660).

No antiquarian could want for a more tantalizing provenance, nor a more

dynamic period in the early pendulum history. I was not disappointed. It

is one of the earliest known Hague pendulum clocks, and a 'Striker'.

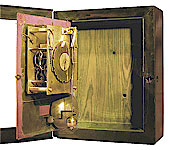

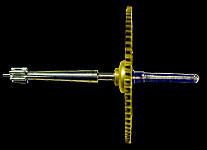

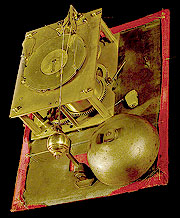

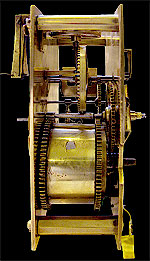

Fig. 1 (click to enlarge)

Oosterwijck's Aristocratic Haagse Klok

(view high res

picture)

Pf.003

●

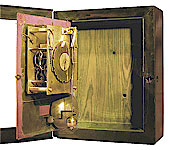

First

Impressions [Fig.2].

Some

works of art, also clocks, have the power to hold the viewer; this is

one such. At first sight, the regularity and quality of the movement and

the dial presented features and components I had not seen in a Hague

clock. I also observed the evidence of an ancient accident involving

both the case and its movement.

Its

workmanship is outstanding, superior to Coster’s pendulums,

notwithstanding the latter's superb watches and table clocks

in the balance-era. Now I better

understand why, in March 1662, Alexander Bruce (Earl of Kincardine),

then Christiaan Huygens (Monsieur Zulichem)

in 1663, each chose Oosterwijck

to make their Longitude ‘sea-clocks’,

(inherently flawed by pendulum control in first instance), then to add

Huygens’ too complex (also flawed)

weight-remontoir in 1664.

Oosterwijck’s 'Haagseklok' or 'Haagseklokje'

("little Hague clock") deserves the fullest appreciation. Its privileged

owners would remain anonymous, yet know more of their heritage and its

context; the restorer would publish via the BHI, a technical audience

not versed in Huygens; and I would bring this rare Hague clock into the

antiquarian fold, via the Dutch Horological Foundation website,

(www.antique-horology.org), with meaningful images also vital dimensions

to promote new research. Knowing that I cannot succeed equally, I offer

my findings, (PART I, "HOROLOGIUM"), also my historical perspectives and

new hypotheses, (PART II, "OSCILLATORIUM").

Fig. O2V

King Charles the Second of

England (1630–1685)

HUYGENS, AUTHORITIES HUYGENS, AUTHORITIES

Readers

not familiar with Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695) and the early

pendulum-era will find the Horological Foundation website invaluable. It

includes a Compilation on the Hague Contract of

September 3rd, 1657, between young John

Fromanteel (1638-1692) and established Hague clockmaker Salomon Coster

(1623-1659) the pendulum patentee appointed by Huygens as inventor. One

long misread, still misunderstood clause alludes to a ‘secreet’, that cannot be the pendulum or crutch which John already

had seen and made. It taxes us yet. This clock may have great relevance.

●

Collections and Exhibitions.

G.B.Shaw once wrote, “if I had had more time, I should have written a

shorter letter!” But gone are the days when Drummond Robertson could

review two neglected Coster clocks in just two paragraphs, (“Robertson

J.D., "The Evolution of Clockwork”, Chap.VI, pp.76-81). Scholarship has

moved on apace, with specialist articles, new reference works;

magnificent Dutch exhibitions, “Octrooi op de Tijd” (Museum Boerhaave,

1979), “Huygens Legacy” (Paleis Het Loo, Apeldoorn, 2004); also great

private collections. Mr H.M. Vehmeyer’s astonishing catalogue, Hans van

den Ende’s museum at Edam -- I was privileged to attend its opening, I

stayed three days! My own study of Hague clocks was helped by many,

especially by the late Willem Hana and the Dutch restorer Mr. L.H.J.

‘Berry’ van Lieshout; many rely on his wide knowledge and unique

archives.

● Didactic

Scholarship.

Professor

Dr. Ir. Reinier Plomp has long been popularising

Hague clocks, by numerous

erudite articles and his standard reference work, “Spring-driven Dutch pendulum clocks, 1657-1710” (Interbook International BV,

Schiedam, 1979). For the privilege extended to me, I presented copies of

Dr.Plomp's book both to the owner also to Paul Shrouder. Lately,

Dr.Plomp has identified “The

Prototypes of Hague Clocks and Pendules Religieuse”, (Antiquarian

Horology, June 2007); he also defined their significant characteristics,

“The Earliest Dutch and French

Pendulum Clocks”, (HF website, Op. Cit.). His matrix is based on 25

clocks, to determine both craft lineages also chronologies (‘D1’, etc.,

for Dutch pendulums; ‘F1’, etc., for French pendulums). Dr.Plomp's

academic and horological credentials place him at the fore, currently he

is about to publish his long awaited tome on "Pendules

Religieuses", the French derivatives of Coster's pendulum clocks.

Here, I follow his line; he may have to revise his chronology.

Dr.Plomp's characteristics’ are not the only ones to be

observed in a Hague clock. Several are too general to be useful; others

too infrequent to compare yet still important. Among these is,

or should be, the unidentified

‘secreet’’ construction– although many have made diverse

attributions.

In

a paper for the Dutch

Horological Foundation, I cited research by Berry van Lieshout and

myself, (HF website, Op.Cit. 2005). Implicitly, on Mayday

1658, a 'secreet' was to be shared between Fromanteel’s and Coster’s clocks.

I pointed out, ‘secreet’ is not a Dutch word at all; “its etymon seems

entirely English; if so what then?” I believe that overlooked etymon

confirms a conspicuous and even important linguistic clue. Might that

contractual secret also be found here in young Severijn Oosterwijck’s

Royal Hague clock?

●

Who was

Severijn Oosterwijck .

Notable authorities, (Robertson, Morpurgo, Edwardes, Dobson, and

Plomp), have cited his life and work. Berry Van Lieshout records,

“Severijn Oosterwijck was born before 1637, son of Adam Oosterwijck

clockmaker of Middleburg (employer of Pieter Visbagh from 1649, after

completing apprenticeship with Salomon Coster); He died around 1694. In

1657, he married a Sara Jans van Dueren at Rotterdam”; [KP. Did he then

know Mr Simon Douw, ingenious Clockmaker of Rotterdam? Already he was a

fine clockmaker, see Huygens Legacy, exhibit 07, balance controlled and

dated to 1655, but curiously bears a Hague signature]. Whereas,

“Severijn is first mentioned in the Hague in 1658, when his first son

Adam was born; he registered there in 1659, first renting near the Spui

[river]; in 1660 he bought ‘De Drie Vergulde Mollen‘ and then took

Pieter de Roo as apprentice”. In 1662, he made two copies of Alexander

Bruce's (Earl of Kincardine) first Longitude pendulum clock fitted with

a double-fork F-crutch, shown to Huygens in London in 1661, both tested

by Captain Holmes. He then constructed Huygens’ Longitude design and, by

August 1664, he also had incorporated Huygens' ingenious but flawed

weight-remontoir, for which Huygens would obtain a Dutch patent; but

chided by Sir Robert Moray, that priority for the remontoir was

[Ahasuerus] Fromanteel’s, he assigned his English Patent (3rd March

1665) to the Royal Society. Robert Hooke had scoffed; he understood that

a pendulum is inappropriate for any sea-clock; as is the weight

remontoir; but inherent defects do not reflect on Oosterwijck’s

craftsmanship. In 1664 Lord Brouncker, first President of the Royal

Society, had one of his seconds’ regulators; Sir Robert Moray in

Maastricht had one too. “Severijn had four, sons, all were clockmakers;

in 1687/8, he and Adam (1658-1695) petitioned the Hague Magistrates for

a Clockmakers’ Guild; and upon its incorporation Severijn became first

Master. Around 1690 he made a year spring movement for Jean Brisson’s

monumental case (modelled on the more lavish Breghtel-van den Bergh case

of 1665-1670, now in the V&A London). Later, with third son Jacobus

(1662-1711), he adapted it into a musical clock, which they signed

jointly”. [KP. It is one of Holland’s horological icons, (see P.C.Spaans

Collection, Lot 421, Christie's Amsterdam, 19/12/07). I saw it with

Eugene Stender in 1976].

Any clock by this particular maker is of interest, and for several

reasons; his part in the birth of the Dutch pendulum clock; his

abilities as a craftsman; also his early part in experimental maritime

navigation to determine longitude by pendulum time-keeping (see Appendix

Three). The subject clock ticks the first two boxes, hence this Royal

patronage; Bruce and Christiaan Huygens himself ticked the third box.

His name never disappoints.

GENERAL OBSERVATIONS GENERAL OBSERVATIONS

●

The Inspection.

Paul Shrouder took down, measured parts, and counted

teeth, as I made notes and shot images (of variable quality). The

minutia of our record is essential towards a better understand of “the evolution of clockwork”. For researchers, the dimensions and

wheel-counts are recorded at

Appendix One; Appendix Two

touches on conservation needed to preserve this unique case;

Appendix Three offers new

lines for study, and proposes an "open-research"

Web project.

●

Originality.

Antiquarian catalogues rarely reveal the extent of any ‘restorations'. For

the benefit of researchers, my examination

found Oosterwijck’s movement to be very original. The few exceptions

are; the mainspring is replaced; the original four-spoke escape-wheel's

collet and pinion are newly made; the original four-spoke contrate wheel

now has a new collet; the original pendulum-rod has a new bob, it now

also has a suspension hook - (the original pulley mount sadly removed);

door glass is replaced. A restorer’s defacing scribbles infer he moved

the hammer and adjusted its clapper, the strike-lever is untouched One

function has been lost, a strange ‘cam’ on the barrel arbor and vacant

pivot holes offer cryptic clues of a unique feature, (see 'Wind-Me' -

Part.II, "Oscillatorium").

Fig. 2 (click to enlarge)

Oosterwijck's Aristocratic Haagse Klok

(view high res

picture)

Oosterwijck's spring clock has the typical strike-gates

and central countwheel, with early internal bell, but also unique

features like the pendulum holdfast (Fig.2).

●

The Unique Features:

Among Hague clocks, Oosterwijck’s movement has features

that I believe to be unique, namely;

| 1 |

|

Octagonal

pillars. |

| 2 |

|

Fromanteel type strap-potence. |

| 3 |

|

Watch-stop

work

hidden under ratchet work |

| 4 |

|

Its

four-spoke escape and contrate crossings are exceptional.

One

lost feature, an Up-Down mechanism? certainly would be unique

among Hague clocks. |

| 5 |

|

Dial:

a

folding pendulum-holdfast; an obelisk bell-stand; and rare

sector cut-out. [His early 'Lieberge'

clock has a date-sector, (Sothebys Amsterdam 21-02-1995, lot

324), as does his later clock, (Plomp R, Op.Cit. nrs.84)].

|

|

6 |

|

Box-case:

hardwood carcass and backboard is constructed from an expensive

show-wood, used in the solid. My initial recognition of

‘Kingwood’ (Dalbergia

Cearencis) has gained expert support. |

Having early

strike work and a

split-barrel* (one

spring serving multiple trains) also mark it out as special. [*Tandem-barrel

misleads, being two or more barrels serving just one train].

Notwithstanding the cited changes, this is a most

original Hague clock and whilst not

virgo intacta, undoubtedly it

is of huge academic significance. But how does it square with Dr Plomp's

earliest characteristic properties?

●

Plomp’s Characteristic Properties, vis a vis Oosterwijck’s Clock.

|

Windows |

P1. |

Earliest simple box,

no side windows, but sound-holes in base

and side. |

|

Door Frame |

P2. |

Early

plain section; Hinge plates are set into 45 deg. angled

mortices, beneath veneers. |

|

Aperture |

P3. |

No backplate

aperture for escapewheel, (higher escape-wheel). |

|

Pillar Shape |

P4. |

Uniquely Octagonal!

|

|

Holes |

P5. |

2 Steady

holes

but for a strap-potence, (higher verge).

|

|

Key |

P6. |

Winding key also

locks the door, (no special key). |

|

Chapter Ring |

P7. |

Pinned

to dial , (not riveted). |

To

pre-empt conjecture, although the subject clock possesses some of the

very earliest characteristics, it probably falls outside the first

experimental

year, 1657. Significant negatives

include: Dial plate is not made of Iron (unlike extant Coster timepiece,

provisionally ‘D1’, Plomp 34); Dial plate is not fixed, and the case has

no rear door nor removable panel, (unlike Coster timepiece ‘D2’, Plomp

35); Hinges are not combined for the dial and door (unlike Coster ‘D3’,

also Fromanteel's English box-cases); Spandrels were never fitted.

●

Comparables:

Oosterwijck’s 30-hour spring clock

with hour strike is most directly comparable with Salomon Coster’s two

known striking clocks; ‘D8’

and 'D10" in Plomp's

chronology;

<Compare Oblique>

(Plomp R, Op.Cit., Nr.38; “Prototypes”, Op.Cit., Figs.6,7,8).

Oosterwijck's clock even has ’Coster

hands’, rarely seen with another maker.

Coster's

split-barrels have a significantly larger diameter, and have larger

centre pinions, than Oosterwijck's Royal clock, but all have a similar

duration around 30-hours, (see

Appendix One, Table 4). Other than a tortoiseshell frame, the box

case of Coster D8, is remarkably similar to Oosterwijck's case, also

having sound-holes. Probably these two cases were made by the same

furniture maker.

Whereas, Coster's next striker

'D10',

and also Oosterwijck’s next, 'D9'

in Plomp's chronology, (Huygens Legacy, Op.Cit., Nr.11), both

possess more decorative hands, signature plates, cases, mouldings, and

movements; all of which signify later dates. Internally, both D9 and D10

are laid out like the earlier Coster D8, and the subject Royal

Haagseklok. All are 30-hours, on 4-wheel trains; but dispel prejudice,

Huygens himself preferred fewer wheels for less friction.

Coster 'D8'

is presently regarded as being the first Hague clock to have strike.

However, I shall advance a new hypothesis - that Oosterwijck's Royal

clock is the predecessor and is also the pattern for Coster's also

Visbagh's striking clocks. I shall also propose an 'open research'

project - to accept and collate trains and other technical data that may

eventually reveal train evolutions, chronologies, and test new

hypotheses. (see Appendix Three).

PART

I “HOROLOGIUM”

The Clock PART

I “HOROLOGIUM”

The Clock

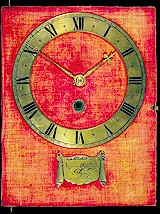

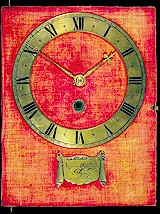

The

velvet dial plate

●

Overview

Oosterwijck’s velvet on brass dial plate, (21.2 x

16.5 cm),

is smaller than all but one of Coster’s - a sure indicator of an early

Hague clock. His superb dial even creates the illusion of a Coster

clock, it even has the earliest steel-tipped minute hand and lobed hour

hand, set upon later velvet of Indian-red.

Swivel pins (L) allow the dial to swing outwards.

(Fig.3).

Fig. 3 (click to enlarge)

Oosterwijck's Dial

(view high res

picture)

The

dial retains Coster’s decorative brass winder-collet, that preserves the

velvet. The cannon opening is oddly irregular, but I could not find

evidence for separate alarm work like Coster 'D5',

nor integral like Coster' D8'

added retrospectively. The typical engraved Lambrequin signature plate

covers the dial's access hole, needed to restart the pendulum, but the

old red velvet covering is not cut out. While it

is not the original velvet, it is fragile

so was not removed to examine the plate.

Co-operation

between these two earliest Dutch pendulum makers is writ large. Even

Coster’s immediate successors, Frenchman Claude Pascal and first Dutch

apprentice Pieter Visbagh, rarely replicated Coster hands but, instead,

each introduced decorative piercings.

Early

Dutch pendulum movements are rarely signed, so only its original

signature cartouche denies Salomon Coster the credit for Severijn

Oosterwijck’s rare clock and outstanding quality.

Just

as the iconic square pillars were initially adopted, the velvet dials

saved the great expense of engraving or matting, and also speeded up the

fabrication of these new clocks to meet demand. Nevertheless, velvet

became the reigning fashion for decades in

Holland,

Flanders

and

France,

but not elsewhere in

Europe nor in

England.

Purple velvet,

from the Purpura lapillus

mollusc, was probably used originally; like another Royal patron’s

baroque gilded console-clock by Johannes Van Ceulen, its case is now

attributed to Daniel Marot, (see Turpin A, “A table for Queen Mary’s

Water Gallery at Hampton Court”, fig.14, p.11 p.14, Apollo Magazine,

Jan.,1999). Matching silk replicates the original appearance, while also

protecting the rare original velvet, much worn and faded where not

protected by the mounts to its most unusual Limewood dial in the French

style.

Fig 05v

Purple velvet on a cartel by

Joh. van Ceulen and Daniel Marot.

Black,

or scarlet, velvet cannot be ruled out, but I reason that the Prince

Charles Stuart (soon to be crowned King Charles II) already possessed

his executed father's French tastes and still held to the doctrine of "Divine

right of Kings”. Therefore, an immediate visual impact, showing

His personal clock’s Royal

status, would have been irresistable.

●

Signature Plate. [Fig.4]

The typical wrought and gilded brass

lambrequin plate, now with a pinned repair to one hanger, is finely

engraved (not etched), and bears a full signature, also Huygens’

license;

Seueryn

Oosterwijck Haghe met privilege”.

Note the phonetic spelling of 'Severijn'.

|

Severyn Oosterwijck

Haghe

met privilege |

Early

signature plates hang on wire loops, over a dial access hole for

restarting the pendulum. The hole is present, but the later velvet is

uncut.

Fig. 4 (click to enlarge)

The signature plate.

Fig. 4a (click to enlarge)

Velvet is uncut.

Though

it bears no date, here I do not doubt that this is the original

signature plate, probably even sourced from Coster’s engraver; unlike

the repoussé plate of his next clock, (Plomp, “Prototypes”, Op.Cit. D9).

[Van

Lieshout privately suggested that Huygens should not have granted “met

privilege” while Coster lived, he died in December 1659. It is a telling

point, since the assigned Octrooi was granted to Coster for a term of 21

years, so it would require both to consent. Even Pascal's earliest Hague

clocks do not bear the legend.

KP. But, also in 1657,

Huygens did grant a second privilege, to Jan van Call in

Nijmegen, (Morpurgo E.,

"Nederlandse klokken en horlogemakers vanaf 1300", p.30, Scheltma &

Holkema, 1970, Amsterdam);

Berry himself privately records a dated clock by Pieter Visbagh,

bearing the legend “Met

privilege 1659". Even Dr Plomp's chronology puts Oosterwijck 'D9',

bearing the legend, before Coster's similar striker 'D10'. Was Coster,

perhaps, incapacitated? Did Huygens anticipate his decease

by granting the coveted privilege to other Dutch clockmakers?]

Herein, therefore, I shall interpret and assess the subject

Hague clock only against the evidence of extant comparables and their

more authoritative dating. However, in the light of discovery of

Oosterwijck's clock and my new evidence, I anticipate lively

contributions on this point.

●

Chapter Ring [Fig.05].

The gilt brass ring is typically

narrow (2.0 cm), of small diameter, (14.3 >

10.3 cm).

It is finely engraved and very well finished.

Among early Hague clocks, its design represents what I putatively

identify as the 'Fourth-state'.*

Roman Chapters,

I-XII, mark the ordinal hours. Half-hours have become stylised

spring-flowers, now with the

Quarters scribed within the narrow inner band; still with Coster's

enclosed ordinal Minutes shown in fine Arabic ciphers,

1-60, in a wider outer band; each Minute is

scored through in early manner. Seconds’ are not shown, though Huygens

showed how in ‘Horologium’, and Philipp

Treffler’s 1657-8 copy does, (see concluding Perspective

6, A Seconds’ Hiatus).

Fig. 5 (click to enlarge)

Chapter Ring

(view entire chapter

ring in high resolution)

[*I observe, Coster's

'First-state' chapter-rings have every minute scored through,

'arrow-heads' mark the half-hours, there is no inner quarter-line;

the 'Second-state' adds

an inner line, yet without

quarter marks; a 'Third-state'

adds spring flower half-hour markers, still without quarter-marks; a 'Fifth-state' has quarters with arrow-heads now sprouting from base

flowers. Another variation,

is where the single minutes (1-9) are not scored through, like Coster

D3, D8, and D10; D3 anyway has an untypical heavy chapter-ring. However,

any particular 'state' (design) might also depend upon the engraver

chosen, or clients' wishes. Chapter ring styles soon proliferated as

pendulum workshops sprouted across

Europe- I understand Hans van den Ende is

preparing a paper on this subject].

The reverse side, too, is also well

finished but shows tool marks, also an indistinct cipher and a Roman

XII 'scribed at the top

stud. This is the original chapter ring, fixed by integral round studs

pinned at the dialplate.

●

Coster

Hands.

Oosterwijck’s ‘Coster-hands’ are

finely wrought and sculpted in gilded brass. These are the original

hands; despite evidence of maltreatment each retains most of their

original fire-gilding, probably the steel tip of the minute hand was

blued originally.

Fig. 6 (click to enlarge)

The 'Coster' hands.

The

rare moon-pierced minute hand, with early steel tipped pointer (7.05 cm),

is held by a domed collet, having a collar and pin-slot The lobed hour

hand (5.1 cm)

is secured to the hour-cannon

by two transverse pins, (Fig.6a). It is instructive to compare

the subject hands directly with Coster's, which are rarely seen on

another maker’s clocks.

Fig. 6a.

Transverse fixing point, to secure the

hour-hand onto the hour-cannon.

Oosterwijck’s

next extant clock (Plomp D9) keeps Coster’s minute hand, but its broad

hour hand has teardrop* piercing, silvered to match the silvered chapter ring in

contrast to its black velvet dial.

*Teardrop piercing is

also found in his Lieberge

clock, (Appendix Three).

Interestingly, when discovered, Coster D3 possessed an untypically

carved and teardrop-pierced

hour hand, with a short trident tail, more reminiscent of early table

clocks. Is Oosterwijck

recalling Coster's original pendulum hour hand?

<Refer D3hand>

●

Dial

Sector

[Fig.7a]

On seeing the dialplate, already

with its movement demounted, I noticed an unusual opening, an

inverted-keyhole below XII,

in the centre zone. The facing velvet is not cut out. If for display,

like Oosterwijck's Lieberge

clock (see Appendix Three), it would be a rare exception to early practice; I

first took it to be for Huygens’ Seconds’ window, alternatively for the

Weekdays and Deities. It proved a 'red

herring’; when the movement was returned to its dial, the vertical

motion-cock recessed flush into the sector. (Coster D8 has a canted

cock, D10 has none). Had extra

depth for a strike-lever been overlooked? Such oversights might be

significant. I had not seen dial cut-outs for motion work in any Hague

clock, except a French inspired wooden dial plate by Van Ceulen-Marot

(see above)*.

Fig. 7a

Dial sector?

The dialplate also has a typical rectangular access

hole, to restart the pendulum, faced by later velvet, uncut like the

'keyhole-sector' above. Tiny vestigial dial studs might be changes of

mind, clockmaker's 'pentimenti'.

The unique holdfast is shown pivoted to the 'rest' position, held

by a sprung geometric lock sited next to the obelisk bell stand.

Fig. 7 (click to enlarge)

Dial opens outwards on swivel-pins.

(view high res

picture)

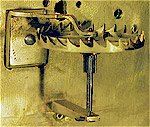

* An

early ‘pendule religieuse’, by

Isaac Thuret of Paris, has a similar cut out dial sector, but only

through the brass false-plate which is riveted onto its fixed iron dial.

[Thuret's dial is reminiscent of the earliest extant Costers;

‘D1’ having a pivoted

iron dial;

'D2’ having

fixed brass dial]. Note

the octagonal steel work to a typical vertical hammer post, here

unusually mounted on the dialplate.

●

Dial

Latch

[Fig.8]

The typical Coster pattern fabricated brass

latch, having a broad flattened spring reversing on itself and turning

into a single scroll foot, being riveted behind the brass dial plate.

The latch has a brass slider protruding through a horizontal dial slot.

Coster's many acolytes adopted it. The surprising exception is Coster

'D10' which has a brass latch but a straight spring.

[Fromanteel's English box-clocks

have brass latches with longer ’S’

shaped springs, yet are recognisably derived from Coster]

Fig. 8 (click to enlarge)

The 'Coster' Dial Latch.

(view high res

picture)

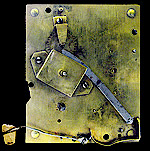

●

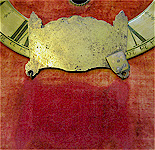

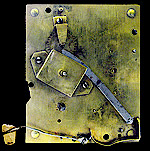

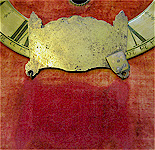

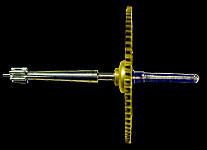

Pendulum Holdfast

[Fig.9]

The exceptional, robust, folding, pendulum-holdfast, pivoting in dial

brackets; its lobed base forms a geometric lock against a broad spring

with “T” shaped foot fixed to

the dial, (with iron rivets, like the repair to signature plate). The

long cranked folding arm ends in a square fork having a delicate

swivel-hook, to enclose and hold the pendulum rod. All edges are

chamfered, it is masterly, and also unique on a Hague clock.

Fig. 9 (click to enlarge)

Holdfast extended, swivel hook

open.

Evidently,

Oosterwijck foresaw that his Royal clock would be moved about, regularly.

[Based on photographs, Van

Lieshout suggests this device is not original, saying if any holdfast

ever was fitted to this Hague clock it may have been pegged into the

backboard, in one of the holes. KP. I do not share his

view. The quality, colour, also the patina of this device matches the

dialplate too closely].

Why

is the holdfast not seen in other Huygens-Coster spring clocks sent to

Italy,

Germany,

France

and

England?

It seems a practical idea, even for a seldom moved spring wall clock. I

suggest it was then envisaged that, once delivered, those clocks would

all live out sedentary existences.

Whereas

this pendulum clock was made for a

Royal Court which, in the changing

fashion of the time, still was often in progress around the realm to

enjoy the hospitality of liege families. Evidently, this clock was

intended to be included in every Royal baggage train.

Fig. 9a (click to enlarge)

Oosterwijck's Aristocratic Haagse Klok

(view high res

picture)

THE MOVEMENT PROPER. THE MOVEMENT PROPER.

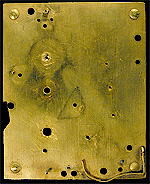

●

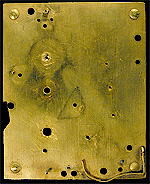

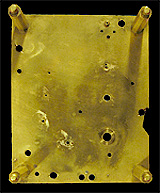

The

Plates

[Fig.10]

The rectangular plates (11.5 x

9.4 cm)

are conventional, any original gilding is now fugitive. Notches (V

- \ /) in the top edges

reveal intended orientations which were ignored when being drilled, (see

fig.15b). That simple oversight had no further consequences.

Fig.

9b

Notches in the plate edges.

The

one-piece front plate is rebated at the left edge for the return of the

drop-hammer; whereas the striking Coster frontplate (D8) has no cut-out

because spacing is greater and its hammer stem is straighter and its

steel clapper is itself rebated. Oosterwijck's front plate has two brass

studs to locate the trapezoid bridge of motion work. [Note. Coster D8

has integral studs on the bridge itself].

A

central steel hammer stop-pin has been made redundant by the hammer

move. There is a steel steady-pin to the left, possibly for a cock to a

lost device (see "Wind-me").

In the lower right corner is a, now misformed, "L" shaped, brass hammer

spring - to assist the gravity drop-hammer.

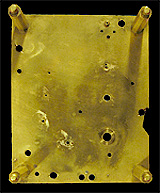

Fig. 10a (click to enlarge)

Frontplate obverse.

(view high res

picture)

The

thick brass 'L' shape

hammer-spring is held by integral steady-pins being pressed into the

plate, its long tail is now reshaped, curled oddly upwards, again caused

by the hammer being moved. Between the central pivots at the lower edge

is an internal post, now reduced.

Fig. 10b (click to enlarge)

Frontplate reverse.

(view high res

picture)

Four,

unique, octagonal pillars are riveted to the plate, giving 3.8cm separation;

1.5mm wider than Coster's D1-D5 plates, but exactly according with

Huygens's spacing, "one and

one-half inches apart", ('Horologium

Oscillatorium', p.15).

Fig. 10c (click to enlarge)

Backplate obverse.

(view high res

picture)

The

single back plate is undecorated and also

is unsigned, usual for all first-period Hague clocks, (compare

his next clock, see Plomp D9, 'Huygens

Legacy' Nr.11).

I should

want to planish out both of the 1970 restorer's accusatory inscriptions,

this (under the count wheel)

defaces the plate.

Fig. 10d (click to enlarge)

Backplate reverse.

(view high res

picture)

The back plate has a central steel stud for the

count-wheel; the brass detent-spring is held by integral studs. The two

small holes adjacent to the detent position are probably for the

spring's first plant which Oosterwijck

then changed.

Riveted inside the back plate is a long brass post of

the lower potence, having dovetail jaws holding a steel wedge - to bear

the vertical escape pivot.

Both

the verge cock and the upper strap potence, have integral steady-pins.

Individual pendulum suspension ‘cheeks’ are screwed high on the plate.

Original tool marks abound, some finishes remain; Paul Shrouder has

conserved these all.

Plomp suggests all the extant Coster timepieces, all

having regular plates (109/110 x 58/59 mm) and square pillars, were in

fact all made by young John Fromanteel. Whereas Coster’s first

striking-clock ‘D8’ required larger plates (120 x

98 mm), like Oosterwijck’s similar ‘D9’,

(117 x

95 mm); both similar to the subject plates (115 x

94 mm).

Is that mere co-incidence or had Oosterwijck the access to

Coster’s workshop, therefore to young John Fromanteel, and thus to new

developments in

England, even to shared ‘secreet‘ construction? Suddenly, attention to every detail

in this clock became paramount.

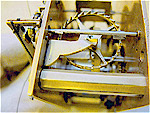

●

Octagonal Pillars

[Fig.12]

Four octagonal brass pillars

(3.8 cm

‘tween plates), are proudly riveted at the front plate and pinned at the

back plate, without flourishes.

Note the early strike-detent 'gates'.

Fig. 11 (click to enlarge)

Octagonal Pillars

(view more on high res

picture)

These

recall square pillars, used by Coster, also Ahasuerus Fromanteel

(1607-1693) in

England,

to reduce time and costs in bringing their pendulums more quickly to

ready markets. A Coster balance-wheel table-clock has hexagonal but

twisted pillars, also square dial-feet, (Vehmeyer,

Op.Cit, Pt.II, Chapt.2,LC7, pp.274-5).

Square pillars are uncommon, but several earlier ones are known,

(Vehmeyer,

Op.Cit, Pt.I, pp.140-161; by Johann Sayler of

Ulm,

(G23, G24, G25); by Andreas Raeb of

Hamburg,

(G29); and lastly in 1651, by Jacub Gierke of

Vilnius,

(G33). On the evidence of Coster's table-clock (LC7), I am inclined to give him

the credit for deciding on time saving square pillars for Hague pendulum

clocks

Whereas

Coster acolytes around

Europe all adopted round pillars, here, Oosterwijck seems to take his lead from

‘Fromanteel-Coster’ square pillars. Curiously, Oosterwijck's ‘Huygens-Thuret’

style long-pendulum regulator has heavy square pillars. (Sotheby's

New York,

13/10/04,

"Time

Museum",

Part.4, Vol.1, lot 518); now in a Dutch private collection.

<Refer_Regulator>

Early

Ahasuerus Fromanteels often have octagonal dial-feet, like his

roller-cage clock at the Museum of the History of Science,

Oxford. Whereas, Coster's Hague

clock dial feet are mostly round; except ‘D8’ having hexagonal dial

feet, and 'D5' having square dial feet like the pillars to its movement

and separate alarm. However, I do not know of another Hague clock having

octagonal pillars; octagonal steelwork is more common.

<Refer_Thuret>

Oosterwijck’s octagonal pillars

probably gave him subtle savings in costs and time, to fulfil his Royal

client’s order for a new Huygens' pendulum clock, but having a visibly

superior movement and the additional novelty of hour striking - but no

alarm. King Charles left

the Hague in May 1660, for

England and His Coronation, we may now presume, with His new

striking

Hague clock in His luggage.

Pf.036

●

The

Motionwork [Fig.13]

The wrought brass bridge, notched with a ‘V’

matching the front plate, its trapezoid feet planted on brass studs

set into the front plate and fixed by

screws. (Fromanteel’s early bridges are also set on plate-studs, later

ones have integral steady pins).

Coster D8 has a rectangular bridge,

Coster D10 has none.

<Compare Frontplates>.

Fig. 13 (click to enlarge)

The motion work.

The

up-stands to the wide bridge are slotted for the reverse-minute wheel

and the strike lever. The cannon is plug-riveted into the bridge. The

wrought brass vertical cock of the reverse minute wheel, with integral

steady-pins is fixed by a dome-screw, it recesses flush into the dial

sector. The frontplate motion work gearing (32_32/6_72) is identical to all

the extant Coster’s, but Oosterwijck's ten strike pins and countwheel

pinion are unlike.

A

hooked barb to a original long, steel, strike lever is tripped hourly by

a pin on the centre minute-wheel. The weighted, strike-lever (Coster D8

is thinner steel, D10 is brass with a return spring) goes diagonally

across the front-plate to the lower of two plain arbors, to pivot the

arbor of the scroll pinwheel gates, all crafted in steel.

Shown

here the hammer arbor is wrongly planted, its brass clapper has been

moved along its own integral dovetail shaft to extend its reach, the

long tail of the hammer spring has also been reshaped. (Coster D8 and

D10 have flat steel hammer shafts, with steel stop and assist springs

mounted above and below the hammer pivot).

This

form of simple hour strike, now regarded as English striking, is also

the model for two striking clocks signed by Salomon Coster, D8 also D10;

also for Pieter Visbagh's D18. While their details vary, their general

layouts are the same.

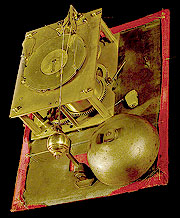

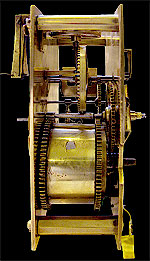

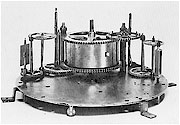

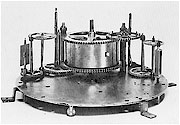

THE FOUR-WHEEL TRAINS THE FOUR-WHEEL TRAINS

Overview

Oosterwijck’s movement breaks new ground, firstly in having a new

‘experimental’ split-going-barrel driving its two trains. I have yet to

see this on device any earlier European going train, where the former

practice was to reserve barrels for striking work, and to always apply a

fusee for the going.

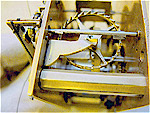

Fig. 14 (click to enlarge)

The

four-wheel trains.

(view high res

picture)

Other wheels have similar evidence of marking-out by

punch or radial scoring, by which I

was

able to show that the abused contrate is the original. Domed brass collets

to the centre-wheel, crutch, warning-wheel and the last strike wheel are

all originals. Dutch trains are usually ‘scribed,

Gaan or ‘G’ (going) and Slag

or ‘S’ (strike); here a single ‘S’ is 'scribed, oddly enough, on the

unmistakable warning wheel.

The rare four spoke contrate and escape wheels are exceptional in any

Hague clock, (see Figures 13 and 15d);

the Hague clock

standard being just three

spokes.

Several

teeth exhibit normal deformations and wear, (see Figure 13a), but

scarred edges to the centre teeth, also the scarred pin-wheel, warning

wheel and escape wheel crossings probably, are all due to the trains

running-on from plate derangement in the accident cited. None detract

from the Royal clock's normal functioning.

[Fig.14a]

However,

I dismiss these as 'age-marks' which do not detract from originality nor

academic interest. Horologists will find the wheel-counts and useful

dimensions at Appendix One,

also two comparable Coster trains of

timepiece D3 and striker D8.

THE WATCH (GOING) PART THE WATCH (GOING) PART

Pf.038

●

Overview:

[Fig.15]

The four-wheel going-train is planted vertically above its spring-barrel,

like the Coster’s timepieces and his comparable striking clocks (Plomp

R, “Prototypes”, Op.Cit. p.202, Fig.8).

Fig. 15 (click to enlarge)

Going train.

(view high res

picture)

Oosterwijck's

centre-pinion is driven from the rear going wheel, like Coster's trains,

but his is now detached from its centre-wheel which is planted at the

front plate and fixed to the centre arbor with a double-domed brass

collet; Déjŕ vu, Fromanteel!

Fig. 15a (click to enlarge)

Centre wheel.

The tapered centre arbor, with centre wheel displaced

from the rear pinion, is a new feature for Hague clocks. The deep

filed (not turned) relief suggests an

ad hoc revision by the

clockmaker to correct

too small a clearance for the split-barrel strike-wheel (S1).

Probably, in that distant accident the front pivot of

the verge was damaged, re-cut and given an extended bushing to

accommodate the shorter, now re-cut, front pivot (see Fig.15b). The

open screw holes are for individual cocks to Huygens' cheeks (to

eradicate any circular error and to hold the silk suspension).

Fig. 15c (click to enlarge)

Verge frontplate bearing.

Both

the contrate collet and the escape collet are replacements; the escape

pinion of five replaces a badly worn original. The potences, verge-cock

also two suspension-cocks are all the originals. The deformed four-spoke

contrate wheel was painstakingly reshaped by Mr.Shrouder. Though abused,

and recently repaired, nevertheless it is the original. My proof of

originality being, its hand-cut teeth, individually marked out by punch,

and having double-ringed rim.

Fig. 15d (click to enlarge)

The double ringed contrate wheel with hand-cut theet marked out by punch.

Accidental damage also caused the escape wheel’s thick

toothed-rim to be re-cut. Extensive scarring to the rare original

four-spoke crossing and potence are clearly evident in Figure 15d.

Fig. 15b (click to enlarge)

The escape wheels' four spoke crossing.

Again I stress, in any Hague clock, having four spokes

to the upper going train is exceptional, the ‘standard’ is just three. Dr Plomp has privately confirmed that he

recalls one other, by Claude Pascal, (Vehmeyer H.M., “Clocks, Their Origin and Development 1320-1880”, Vol.I. Pt II.,Chap.2, LC14,

pp.288-9).

Conversely, in Ahasuerus Fromanteel’s early

pendulum

oeuvre three spokes are infrequent, although the original strike

train of his most famous

pre-pendulum Chef d'Oeuvre,

(a Solar-Zodiac-Musical clock, made in 1649 for Dudley Palmer of Grey's

Inn, the most famous clock of its time), includes

three-spoke wheels on high

domed collets. [Original

cross-beat and remontoir trains were the subject of early conversion to

a pivoted verge pendulum with remarkably small,

uncrossed, contrate (7/28) and

escape (8/11) wheels].

We

may assume, therefore, that John Fromanteel’s use of three spoke going

wheels, in

Holland, was copying Coster’s

pattern, under contract. Oosterwijck’s independent use of four-spokes,

in his upper going train, together with his novel centre arbor layout,

and strap potence, might all infer an unknown and earlier connection to

the Fromanteels in

London, or a knowledge of their clocks.

Early

Hague clocks did evolve very quickly; a minor consequence of early hand

cutting is that the upper wheels are often larger, with fewer teeth,

having coarser pitch, than later engine-cut equivalents. Trained

watchmakers, like Coster, had their own standards - but the early

conversion of Fromanteel's Zodiac clock has 7/28 and 8/11.

Another

consequence of their rapid evolution is even Coster’s going trains are

not uniform. (see Appendix One,

Tables 4, 5, also Appendix Three, matrix). Oosterwijck’s train

relates directly to

Coster’s

timepiece ‘D3’ and striking clock ‘D8’; their escape wheels are 5/27 and

5/29, Severijn’s is 5/27; Coster’s contrates are 5/64 and 5/60,

Severijn’s 5/60. Such similarities are not by chance; they even hint at Severijn’s going train

being a transition, ie. between Coster ‘D3’ and ‘D8’. It is compelling

evidence, but of what; fraternal co-operation or industrial espionage? I

prefer the first.

Future

researchers may give greater weight to the evidence of wheel-counts and

train designs, to determine origins and chronology. Here I give credit

to Dr.Jeff Darken and the late John Hooper who recorded all wheel trains

in their book, “English 30 Hour

Clocks”, (Penita Books, 1997). Those typical English trains have

upper pinions of 6 or 7, even 9, whereas Renaissance pinions of 5 are

typically found in early Hague clocks. Berry van Lieshout has long

recorded the details of their trains, in his unique database, notes,

images, also AutoCad layouts; but he also adds a caveat, "the demands of

any train may well give identical and yet independent solutions".

Nevertheless,

it is possible to deduce much from wheel-counts, also wheel forms.

Arbors and collets too can reveal lineages. Coster ‘D1’, ‘D2’, ‘D3’ ,

‘D4’ also 'D8' all share

integral steel collets at the front of the centre arbor; whereas 'D5'

does not; only the barrel-arbors of

'D3' and ‘D4’ extend beyond the back plate, only 'D4' has a

turned flourish (like Reijnaert's pillars). Coster ‘D1’ and ‘D3’, have

square collets, behind the contrate; Coster ‘D4’ has a shapely

French collet at the front.

And Coster D3, alone, has a dovetailed barrel-cap; also thinner and

unrounded ends to its pillars; and when discovered an unique hour hand

with an open teardrop trident pointer - not out of place on a

Renaissance table clock. There is an abundance of similar unpublished

data with Van Lieshout and others, therefore I propose an

Open-Research project under

aegis of the Horological Foundation from data inputs by owners, curators

or restorers of early clocks, (see

Appendix Three and

'open-research' matrix).

●

Astronomy's Pendulum.

Huygens was fully aware that the real kernel of his intellectual property,

which he assigned in Coster’s June 16th 1657 Patent, was his

crutched verge, that regulates

his clock directly from astronomy’s freely suspended pendulum, loosely

held within the jaws of his patent crutch. It was a simple construction,

yet a profound insight. He deserved his glory.

Yet

Huygens’ way was very unlike Simon Douw’s

spring-remontoir

with a beam balance,

(cross-beat?), which he and Coster had failed to quash in their

ill-motivated 1658 litigation. Huygens’ way differed radically from, and

was far superior to, Galileo’s pivoted pendulums (1635 and 1642); better

too than Fromanteel’s pivoted pendulum. However, by 1664, even Huygens

had acknowledged Fromanteel’s “new

way of long-pendulum”,

which then founded the long English ascendancy. [Fromanteel’s equation

clock at Belmont reveals an early conversion from the original verge

long-pendulum circa 1662, firstly to

cross-beat pallets on a saw-wheel

(Burgi’s third cross-beat) circa 1664, before its third incarnation

as, so-called, ‘original

anchor' circa 1670 - now with an even later overhead regulation].

Oosterwijck’s original Huygens-type pendulum rod, in

Mr.Shrouder’s images (HJ, Op.Cit. p.382, Photo2), then still retained a

small, flattened, bracket plate at the top. He made a new brass bob, but

he also replaced that tiny bracket with a hook; more appropriate for

later Hague clocks and French variants. Yet that tiny vestigial bracket,

certainly, had once held a small shrouded pulley, for the

silk-suspension. Few Hague clocks now retain it, now known only to

Huygens' scholars and Hague clock specialists, I have not seen it in

Pendules Religieuses. But it

can be seen in Huygens’ original 1657 Patent design, (ie. Figs.I, II,

Horologium Oscillatorium,1673);

also in Perelli's 1770 drawing of J.P.Treffler’s 1657/8 copy of Coster’s

clock (Plomp. Op.Cit. Fig.9); also in Isaac Thuret's regulator

(Vehmeyer, Op. Cit., Vol.II., Part II., Chap.5. pp.810-811, F20). This

seemingly inconsequential part, actually serves an empirical purpose, it

spreads and flattens the suspension chords to squarely meet the face of

the cheeks. Lack of it gives a twisted strand prone to banking. [Its

ultimate expression surely was in Huygens' triangular pendulum].

Happily, when I first saw the clock, Paul had kept the removed part so,

eventually, it might be reconstructed.

● Crutched-Verge.

Oosterwijck

uses Huygens’ patented crutched-verge. The accident-reduced steel verge

is pinned to its brass crutch through the collar of a domed brass collet

unlike the steel block of Fromanteel's pivoted pendulum. Refaced pallets

are set in boxes on the verge; similar pallets are to be seen in other

Hague clocks,

so this appears to be the original verge.

The long stem of the thick brass crutch is bent

outward and forked, to accept the round iron pendulum rod.

Fig. 16 (click to enlarge)

Hyugens' crutched verge.

The

unusual open fork has two transverse pin-holes, unique in my experience.

Their purpose must be to contain the pendulum, like Coster’s loop, but

probably easier for making, also for attaching the simple rod pendulum -

without the later flat section.

The

crutch was the true intellectual core of Huygens' pendulum invention,

patented by Coster, and used

here by Oosterwijck with both their consents, as evidenced by the

legend, 'met privilege'.

[Van Lieshout suggests these may be English

book-pallets, inferring their

replacement post accident?

KP. I suggest any competent

repairer would not repair a broken pivot, add a new form of pallets,

only to then extend the front bushing to accept his shorter verge].

●

The Verge-Cock.

The

wrought brass, single-foot, verge cock has integral steady-pins, fixed

by a single screw. It is planted at left, opposite the internal strap

potence. It is the original cock, but its form, size and position is

unlike any Coster clock, (or Hanet, Pascal or Visbagh); with the

significant exception of Coster's first striker D8 which also is on the

left, but has a trefoil foot. (Coster's timepiece alarum D5 has a

double-foot, back cock like

Fromanteel's, but it appears to be a French reconstruction). The subject

clock's recent conservation and corrected verge alignment has left an

extra pivot hole from a poor repair when broken in the cited accident.

Fig. 17 (click to enlarge)

The verge cock with integral steady-pins..

Like

Hague clocks of all periods, this verge pivot has not the benefit of

Fromanteel’s earliest steel-shim,

roller-cage, or

steel knife-edge; being his trademark attention to details towards

perfection.

End

of this section, click

here to continue.

back

back

|

(Table of contents

continued)

•

The movement proper.

The Plates

Octagonal Pillars

The Motionwork

•

The four-wheel trains.

•

The watch (going) part.

An Astronomer’s Pendulum.

Crutched-Verge

The Verge-Cock

Suspension Cheeks

Strap Potence

•

The strike part.

Strike ‘Gates’

The Fly

Count wheel, Detent and Spring

Hammer

Bell on Dial

Split (Going and Strike) Barrel

(the strike part??

Ratchet-work

(the strike part??

Stop work

(the strike part??

Concealment

(the strike part??

The ‘Wind-Me’ Option?

(the strike part??

•

The unique

box case

•

First Assessments.

•

Dimensions and construction.

•

PART II

OSCILLATORIUM

Perspectives & Hypotheses

•

Concluding Perspectives.

Coster’s Other Contracts?

Makers of Coster Striking Clocks?

Fromanteel Connections?

Hidden ‘Secreet’ Constructions?

Personal Associations?

A Seconds’ Hiatus?

Claims to Priority.

•

Sebastian Whitestone's discovery.

Reflecting on the

1657 contract

•

General Conservation

Issues &

Valuation?

Oosterwijck's Box Case

•

Open research

projects.

Early pendulum clocks

matrix

Significant

early makers

Comparable Wheel Trains

•

Acknowledgements.

•

Oosterwijck

Bibliography.

•

Picture Gallery

(the author's original untouched pictures)

Back to end of previous section.

Back to end of previous section.

●

Suspension Cheeks.

Huygens' famous ‘Cheeks’ were not

part of his design, he claimed for Christmas Day 1656, (Plomp R, Op.Cit.

Fig.4). However, he quickly identified circular-error (periods of oscillations varying, due to the changing amplitudes of

fixed-radius pendulums) that Galileo and Wendelin had observed, but

had not resolved. Seeking to cure that significant defect by empiric

means, early in 1657, Huygens first arrived at cheeks to change the

radii of a suspended pendulum with changing amplitudes, to minimise

circular error.

Huygens'

privilege also extended to

Oosterwijck using pre-cycloid cheeks, evidently without any allegation

by Coster or Huygens of plagiarism or litigation: which indicates to me

their full cooperation in this English Royal commission.

Oosterwijck's two laminae (Cheeks) are set

higher on

the back plate than Coster's. Each separate cheek has a round cock (foot), fixed by

elongated ball-head screws, joined at their contact point by a single

screw clamping the thread. These original unmodified cheeks are an

incredible rarity. [Van Lieshout identified the baroque Van Ceulen

repeating movement as another, no less rare in that later period].

Fig. 18 (click to enlarge)

The pre-cycloid suspension cheeks.

Each cheek has two pinholes at its lower end, I had not

seen that before although Coster ‘D1’ does have single larger holes at

the top. Paul Shrouder neatly resolved these pinholes, by threading the

silk suspension so as wear occurs new thread may be pulled through.

Oosterwijck’s

suspension cheeks already display his empiric form but are, technically,

still ‘pre-cycloid', like

Huygens' original 1657 timepiece (see 'DŘ1' below) and, oddly, still

depicted in Horologium Oscillatorium (Part I, Fig.II); a true cycloid

form is also shown, (Pt.I, p.21, Fig.2).

[Note.

Huygens' original and patented Seconds' clock had his suspension cheeks,

but he abandoned cheeks in subsequent 'OP' design, intended to reduce

its half-second pendulum arc to eliminate circular error (Horologium,

1658, Op.Cit.). By 1660,

he had determined its ideal shape was a

Cycloid. Probably, some cheeks

were reshaped retrospectively; or even replaced (like D8) but his

geometrician’s, incremental

evolutes, proof was only

published in 1673; he credited

Christopher Wren as the first to determine the cycloid's arc-length,

('Horologium Oscillatorium',

Op.Cit. Part II, Proposition xv, and Part III, Propositions VII,

IX)].

●

Strap Potence. [Fig.19]

Dr.Plomp regards the simple verge-cock as an English tradition (Plomp R,

“Earliest”, Op.Cit. Conclusions, pf.3). He says nothing about the

typical Dutch escapement 'potence

block' (riveted or screwed) used since Gerardus Vibrandi's time -

derived from earlier German watches. Pertinently, Coster was firstly a

trained watchmaker, who later took to making table clocks before Huygens

fortuitously offered him his pendulum Patent and rights.

Oosterwijck's

four-wheel train’s high escape wheel and extra long verge does not

follow Dutch practice. He has resolved his higher geometry with a

strap-potence, of wrought brass, mounted on the going side, its foot

fixed by integral steady-pins and a screw; its curved pivot-arm bends

under the verge to the escape wheel’s top pivot. This part, too, appears

to follow an entirely English tradition.

I

believe this strap form is unique among Hague clocks. His novel strap

potence has an external screw, which enables the escape wheel to be

detached without needing to separate the plates.

It seems much closer to the English form adopted by the Fromanteels

for their horizontal verge with pivoted-pendulum, ie. suggesting a

contemporary English pendulum existed.

Déjŕ vu, Fromanteel!

Fig. 19 (click to enlarge)

The cast strap potence.

●

Post Potence.

The lower potence is a long, tapering, brass post, riveted into the back

plate, having inferior dovetail jaws holding a steel wedge to bear the

escape-arbor's pivot. [Coster's lower strap-potences all have similar

dovetails, D1’ and ‘D4’ still have steel pivot wedges, ‘D3’ now has a

brass rivet through the dovetail].

Fig. 19a (click to enlarge)

Escape Wheel and 'English' Potences.

Oosterwijck's might be mistaken for English potences;

that might prove significant. Among Hague clocks this is an isolated

even unique, appearance of the upper strap-potence Ahasuerus Fromanteel

favoured, (Lee, Ronald A, “The

First Twelve Years of the English Pendulum Clock” 1658-1670,

Exhibits 3,13,30).

Whereas all ‘Costers’ and his acolytes' clocks have the

typical Dutch riveted escapement block, with a lower strap-potence,

Fromanteel's distinctive potences had originated from the English

vernacular lantern clock. [Note. as happens in research, I have learned

of a second Oosterwijck movement with a strap-potence, and a fusee,

(exceptional in early examples). After 1680 some Hague clocks were

fitted with fusees, as, by then, several English makers, Joseph Norris,

the Fromanteel brothers, and Steven Tracy had set-up in Amsterdam and

Rotterdam; they first adopted Hague going-barrels but later introduced

fusees as standard, even with Cheeks - "when

in Rome"].

However,

Coster's form is also seen in the rebuilt dated Fromanteel, (Plomp R,

Op.Cit. Fig.22), yet Simon Bartram’s pendulum watch-clock now has

Fromanteel’s strap-potence, (see “Horological

Master-works”, Exhibit 6, AHS,

Oxford, 2003). However, the authors

cite evidence of a “Dutch type top

stud [potence] as illustrated by Huygens in Horologium Oscillatorium

which carried the crown wheel and front verge pivots". A caveat to

those who would impose their own agenda.

Among

Huygens' many sketches and diagrams, only one depicts a strap-form top

potence, (see Horologium,

Fig.1, Sept.1658). Uniquely intended for Huygens' verge-pendulum, was

that strap form known to him from an English model, or from

Oosterwijck’s extant clock? The latter might suggest that his design was

only prepared after seeing the subject Royal clock; the former implies

that Fromanteel’s pendulum, in fact, was contemporary with Coster’s, or

earlier?

When

Oosterwijck made his Royal striking-clock it was

‘state of the art’, and approved by Huygens, certainly not a pirated

copy. His next striking clock (Plomp D9) has similar cheeks but these

(now) mimic the true cycloid shape. (see

Huygens’ Legacy, Op.Cit.

nr.11, p.35); the authors date that lavishly decorated clock, “c.1660”.

Here I stress, it is exceptional for any extant Hague clocks to have

original also unmodified cheeks. So many cheeks

have been

modified, improved or even added, mostly during commercial restorations. When discovered, even Coster D8 had Fromanteel's imperfect pivoted

verge-pendulum escapement; Dutch pride has required its present Huygens'

escapement to be reconstructed. [Conversely, superb English turntable

clocks by East, Matcham, Ebsworth, all recently found in

Europe, had all been converted to

Huygens' improved

escapement].

<Refer Ebsworth>

THE

STRIKE PART THE

STRIKE PART

Huygens

had always disclaimed striking systems as being already well known and

not part of his invention, (Horologium, 1657, p.15). Here I can find no

evidence for any case mounted alarm work, unlike Coster 'D5', nor an

integral alarm such as was added to the plates of Coster 'D8'' by a

different yet contemporary hand. But, this is one of the first Hague

clocks to have striking, if not the first!

Like

Coster’s extant striking

clocks, Oosterwijck’s clock

strikes the full hours only, not the half-hours; now called ‘English

striking’. Like Coster’s, his 4-wheel strike-train runs diagonally

across the plates, (see Fig.13 above); Dr.Plomp suggests that Coster

'D10' is “actually a timepiece with a striking train added”, (Plomp R,

"Prototypes", Op.Cit. p.202, Fig.8). Curiously, for that decorated,

therefore later clock, D10's plates (109 x

84 mm)

are smaller than the earlier

D8 plates (120 x

98 mm), and are also smaller than the subject Oosterwijck's plates (115 x

94 mm).

It needs considering.

Is

there an anomaly here? It would seem so, generally smaller is earlier.

Only the plates of Pieter Visbagh’s first known Hague clock, circa

1659/1660, are smaller ('D18’ at 100 x

78 mm). Might Coster 'D10' be using early plates, set aside then used later? Or

is it new evidence of sparing expensive materials? We may expect

anomalies. Here I suggest, if Oosterwijck's subject clock had lost its

signature plate, then its dimensions, plain gate arbors and steelwork

would now see it lauded, indisputably, as

‘earliest’

in Coster's striking clock chronology. [One Johannes Van Ceulen

clock suffered just such a misattribution].

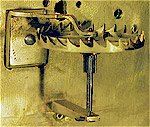

● Strike ‘Gates’.

Hague

clock strike-gates, (or warning and pinwheel detents), are relics of

their Renaissance table-clock antecedents.

A long weighted steel strike-lever goes, from its hooked barb at the

minute-wheel, down and across the front-plate to the lower of two plain

arbors bearing the original scroll gates crafted in steel, mounted

across the plates.

Oosterwijck's

gates are of scroll form, on simple round arbors, and are comparable to Coster's - but being on plain arbors are earlier.

Among comparables, Coster's 'D8' has more central reversed 'C' scrolls,

set upon decoratively turned arbors, with plain locking detent and steel

spring - now with replaced fancy detent and spring, like subsequent

striking clocks by Oosterwijck, Hanet, Pascal, and Visbagh. (Plomp,

“Pendulums”, Op.Cit. nr. 38). Coster 'D10' has even more ornate gates,

and bolder baluster arbors, also an untypical (if original) rudimentary

steel spring to a stubby angular locking detent. Details differ, but

layouts comply.

Fig. 20 (click to enlarge)

The strike 'Gates'.

(view high res

picture)

Evidently,

in their pendulum clocks, the English makers omitted these strike gates.

Even Claude Pascal’s first gates are rudimentary; but subsequently,

Dutch and French gates soon became most elaborate, later becoming

vestigial, finally discontinued after 1700.

●

The Fly.

[Fig.21]

A

heavy, cast-brass, lozenge (Rhombus) section fly is held by a narrow

leaf-spring, slotted across its edges at the rear pivot. Its arbor has a

5-leaf pinion. This heavy

fly's inertia, also momentum, must be considerably more than any

thin-vaned fly.

Fig. 21 (click to enlarge)

The heavy cast brass fly.

This same lozenge fly is also found in the

seventh Coster ‘D10’.

Coster ‘D8’ has an unreduced profile with a wider open section,

to further reduce the fly rotation speed with its 6-leaf pinion? Coster

fly-chronology seems reversed but Dr.van Grimbergen, director of the

Museum of the Dutch Clock,

Zaandam, suggests that Coster 'D8' had originally possessed a 5-leaf pinion. Was

its consequently slower fly then a lozenge? Van Lieshout suggests the

subject fly-pinion, of 5 off 48 teeth, is unusual; he also suggests its

heavy lozenge fly was probably to counter a stronger, second, mainspring

post-accident.

KP. In view of the clock's

long English provenance, why does its Rhombus fly exactly match

Coster's lozenge on ‘D10’, and be so similar to Coster 'D8' too? I

regard these facts as clear evidence of an uninterrupted single-path

evolution].

●

Count wheel, Detent and Spring.

[Fig.22]

The

long front plate strike-lever, with a large barbed drop, resembles

English lantern clock practice. Like early Fromanteel also Knibbs, the

lever is directly tripped at the minute-wheel, not from the

reverse-minute wheel.

The large central count-wheel (7.2 cm

diam.) is set on the back plate, mounted onto a central steel stud

secured by a circular brass key-plate. It has a flat profile, it is

un-numbered and ringed, being controlled by a simple steel detent having

a looped brass spring. Vacant holes below the detent were possibly for a

trial or prototype spring that obstructed the operation.

Fig. 22 (click to enlarge)

Count wheel, detend and spring.

A thick round brass spring, is fixed to the back plate,

held by integral steady pins, its reversed tail tensions the spur of the

vertical locking-detent; like Coster D8. Whereas, D10 has much smaller

detent and spring components.

<Compare Backplates>

Fig. 22b (click to enlarge)

Riveted to the reverse of the count wheel is a large (5.0 cm) four-spoke

wheel with 78 teeth, driven by a small brass pinion of 10* leaves set on

a squared pinwheel arbor,

(view high res

picture)

Riveted to the reverse of the large count wheel is a

four-spoke driving wheel of 5.0cm diameter. having the standard 78

teeth, but driven by a small brass pinion fitted onto the squared end of

the pinwheel arbor and having only 10*

leaves (see Figure 22a). The pin-wheel too has only 10* steel pins. The warning wheel has two brass pins, one pin being

re-sited by 18mm, probably due to the cited accident. I suggest the use

of tens is evidence towards an earlier chronology.

*Evidence for chronology?

Coster ‘D8’ and ‘D10” each have 12 pins and 12-leaf

pinions, not the Royal clock's 10' pins and 10-leaf pinion; otherwise

all three have identical gearings.

Therefore the change from 10s, henceforth to the new

standard using 12s, again points to Oosterwijck's Royal striking clock

as being earlier in Dutch chronology than Coster's D8. It is not the

derivative I first assumed.

This

new evidence, infers that Hague clocks having 12 pins also 12 leafs in

the ubiquitous new standard, are actually all derivatives of

Oosterwijck's new pattern.

Anomalies

such as these, I put it no higher, do make the case for a well supported

open-research project to assemble and collate the physical data for

custodians and researchers to access, (See

Appendix Three, open-research

matrix).

● Hammer.

[Fig.23]

The

brass drop-hammer, with steel striker, is dovetailed to a long steel

stem, which pivots along the plate like early horizontal table clocks.

The hammer arbor is now mis-planted in secondary pivots, (Figure 23),

requiring the brass

clapper to be extended along its dovetail stem, to clear the frontplate

cut-out.

Note the original stop-pin, and

former shape of the hammer-spring. At first we took these vacant pivots

to be for a half-hour passing strike, but that would not require the

unique barrel-cam probably associated with vacant pivots, also screw

holes and posts for cocks, (see 'Wind-me'). Fig.24 shows the hammer in

correct pivots.

Fig. 23 (click to enlarge)

The hammer now wrongly planted.

The Royal clock's nearest comparables, Coster 'D8', has

the same general layout and very similar proud rivets to the four

pillars. Its diagonal strike lever is of thinner steel, its hammer is

all steel having a thick flat-stem to a rebated pear shape clapper

-needing no front plate cut-out, and also pivots along the plate from

right. Its long diagonal hammer spring

is set high on the left with a stubby stop-spring below. Coster D10 is

very similar but with a brass strike-lever.

Whereas the winder squares of both D8 and

D10 have unusual cross-pins at the front plate. <Compare Frontplates>

[Vertical hammer-posts first

appeared in 1659-1660, probably introduced by Hanet or Pascal, and soon

became the Franco-Dutch standard, even having a short lived English

manifestation with Fromanteel and his acolytes, including the famous

Samuel Knibb and renowned nephew Joseph Knibb, even Tompion].

Pf.066

●

Dial Mounted Bell.

[Fig.24]

The

undisturbed bell stand with its original high-domed heavy bell, is

mounted on the rear of the dial plate, on a beautifully crafted obelisk,

with the dome facing out like the two known striking clocks which bear

Salomon Coster's name.

Fig. 24 (click to enlarge)

Bell on dial.

●

Split-barrel (Going and

Strike).

Overview.

The single advantage of the “going-barrel”, over the fusee system, is

uninterrupted power to its going-train on rewinding; it needs no

maintaining power but its varying force is uncompensated. Therefore,

historically, it was solely used for subsidiary trains, not for

timekeeping. The ancient spring-barrel evolved to drive two trains, I

give it nomenclature of ‘Split-Barrel’,

or pedantically,

‘Split-Subsidiary-Barrel’.

Certainly, this did not first appear during the mid-1650's,

coincident with Coster's new 'Haagseklok'.

Fig.

25 The split-barrel

Jost Burgi (1552-1632) of Kassel, (later Prague), is now credited with inventing the

first known

'split-barrel', driving separate Quarter and Hour trains in

his famous series of Globes, circa 1582.

fig. 25a (click to enlarge)

Split-barrel in Burgi's (Anton Eisenhoit)

Armillarsphäre, 1585.

Nordiska Museet Stockholm.

Jobst Burgi 1552-1632

Within Burgi's

Armillarsphäre, for Anton Eisenhoit circa 1585, is the

'split-barrel' he had

developed to drive two trains, striking Hours and Quarters.

(Acknowledgement to Nordiska Museet,

Stockholm).

Subsequently,

for decades, German clock makers used the split-barrel exclusively for

that purpose; never for going trains; the

Fusee alone reigned supreme in

their dominant City Guilds; In 1657/8, Philip Treffler of Augsburg even

added a fusee to Coster's

early going-barrel, as did

Bruce's sea-clocks (see 'Hollar' 1667).

Exactly

when, where and who adapted Burgi’s

split-striking-barrel for

Going and Striking is not known. Significantly, the

going-barrel, also its

variant the

split-going-barrel, were

only possible assuming an

erroneous premise that Galileo’s new pendulum, used in Huygens’ way, had

no need of regulated power. All Dutch and French makers relied on that;

but German, and English makers ultimately, did not. Fromanteel was one

of the first to use the going-barrel, then one of the first to re-divide

his trains, and barring Treffler was probably first to re-introduce the

fusee (with his spring maintaining power; being derived from his 1649

spring-remontoir).

It is almost written in stone, Salomon Coster made the first

Dutch pendulum clock, also the first to have strike work. His strikers, D8’ and ‘D10’, share Oosterwijck’s split-barrel. It became

ubiquitous in

Holland, French makers adopted it too but soon re-adopted multi-barrel formats,

like the English had before them, and both before the Dutch. Dr.Plomp

has the "tandem-barrel" as Coster’s contribution (Plomp R, “Prototypes”,

Op.Cit. p.202). That hypothesis would depend on the nature of his

supposed contribution.

Having

studied Oosterwijck's work, I now suggest that this seemingly mundane

device is actually fundamental to any understanding of ‘Hague-clocks’,

and very probably the Hague Contract of September 3rd,1657,

between Coster and Fromanteel, or

Fromanteel and Coster. In the light of Oosterwijck's construction,

Coster's priority must now be re-examined. I shall examine and consider

the

device as, potentially, the secret

device, and I will review the circumstantial evidence to discover

whose intellectual property it might be, and whose it is not, citing

'priorities' with all consequences. (See concluding Perspective, Nr.4)

●

Pendulum Applications.

Oosterwijck’s

split-barrel (diameter

4.3 cm,

2.5 cm

long), drives separate first-wheels for his

going and

strike trains.

Its weaker new mainspring (the clock’s

third) has thirteen turns but

just six are useable. That gives it a duration of 30 hours; or much

longer without strike.

(G1

has 72 teeth, S1 has 80 teeth).

Oosterwijck’s

new split-barrel has a deceptively simple appearance, showing bold

ratchet-work at the front. But, it is much more complex than is

apparent. Here I describe its parts, so that its underlying

characteristics and unique intellectual property is made clear.

Having

by this time already formed a considered view, that both of Coster’s

extant striking clocks are later than the subject clock, and on the

basis of features I shall disclose, this may well be the earliest "split-going-barrel" yet observed in any pendulum clock.

The going-wheel,

(G1, 72 teeth,

4.94 cm

diameter), is riveted onto the rear of the barrel. It drives the centre

pinion (6 leaves) with a shaped arbor having a centre-wheel (70 teeth)

at the front; unlike any of Coster's movements. The barrel's rearmost

cap has been left roughly filed.

The strike-wheel,

(S1, 80

teeth,

4.95 cm

diameter), forms a front cap, being pinned onto the squared arbor. A now

internal set-up ratchet is affixed to the wheel, unlike Coster’s

timepieces with ratchets set on the front plate. (Coster 'G5', early

Pascal timepieces and later Hague clocks set the ratchet-work onto the

back-plate). Oosterwijck’s 'split-barrel' appears to be conventional.

It is not!

● Ratchet-work.

[NL.Palrad, Ger.Sperrad,

Fr.Rochel,]. The

purpose of ratchet-work is to set up a

minimum spring tension, to get

a more equal mid-range force. Further, if a strike train is fitted, to

always reserve sufficient spring-power to operate the strike to the full

duration. Comparable Coster strikers, D8 and D10, have ratchets on the

front cap, behind the front plate. (Both have cross-pinned winder

squares - which at present I cannot fully explain without dismantling -

although one Van Ceulen has

its winder squares pinned to round barrel arbors].

Fig. 26 (click to enlarge)

Ratchet work

(view high res

picture)

The solid and seemingly ordinary strike-wheel (S1) forms

the front barrel-cap. Set proud, it mounts a thick circumferential

brass-spring to a steel click, engaging with the domed steel ratchet

(3.44cm, 21 teeth), secured by a stubby steel collar, having an unusual

'spur-cam', at the lower of

the two stepped squares below the winder.

This appears to be a typical split-barrel, having a typical

set-up ratchet and click pegged onto the barrel, like Coster D8 and D10,

but having no stop work. It is not!

●

Stop work.

[NL.Opwindbegrenzing,

Ger.Stellung,

Fr.Arretage,].

The

purpose of stop-work is to limit

spring tension and to prevent

over-winding, that might bind the spring or damage its attachments.

(Britten, FJ. “Watch and Clock- makers’ Hand- book

Dictionary and Guide”, SPON, 1938, p.415). If ratchet work were not

fitted, the stop alone might also 'fix' a range of travel for the going, and maintain minimum power for