A R T I S T S

& M E T H O D S & H O R

O L O G I C A L L E X I C O N

More Pages and links to help you making write ups':

Sample

write ups' for bracket clocks, chronometers and barometrs (more

to follow).

Symbols

Explained (text)

Symbols

Explained (pictures)

Portraits

and names of horologists:

Write us to

add

your item

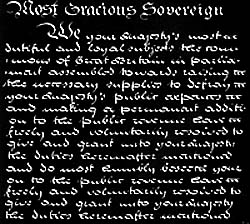

English tavern clocks are often named an 'Act of Parliament clock' due to the tax imposed on clocks and watches in July 1797. The 'Act' was hand-written on a scroll and granted certain duties on clocks and watches to His Majesty (George III)

|

|

A

summary of the very lengthy Act: |

The Act was very

difficult to enforce and led to a dramatic decline in the horological

trades. After intense lobbying it was repealed, nine months after it had

been enforced and at the end of the three quarter period on April 1798.

The name 'Act of Parliament clock' is a misnomer as the particular design

of the tavern clocks had ceased to be made at the time the 'Act' was

passed in 1797.

Source: English Dial clocks, R.E. Rose.

Arbor. A synonym of axle. A toothed wheel is fixed to the arbor, which is usually cylindrical, and both revolve.

John Arnold 1736-1799

|

Assortiment.

French term for the three parts of the escapement (escape-wheel, lever and roller). Generally, specialist companies supply watchmakers with the lever assortment. |

|

Atmos (portraits) In 1928 a

Neuchatel engineer called Jean-Leon Reutter built a clock driven quite

literally by air. But it took the Jaeger-LeCoultre workshop a few more

years to convert this idea into a technical form that could be patented.

And to perfect it to such a degree that the Atmos practically achieved

perpetual motion. In 1936 the Manufacture began production of the Atmos.

The technical principle is a beguiling one: inside a hermetically sealed

capsule is a mixture of gas and liquid (ethyl chloride) which expands as

the temperature rises and contracts as it falls, making the capsule move

like a concertina. This motion constantly winds the mainspring, a

variation in temperature of only one degree in the range between 15 and 30

degrees centigrade being sufficient for two days' operation.

To convert this small amount of energy into motion, everything inside the

Atmos naturally has to work as smoothly and quietly as possible. The

balance, for example, executes only two torsional oscillations per minute,

which is 150 times slower that the pendulum in a conventional clock. So

it's not surprising that 60 million Atmos clocks together consume no more

energy that one 15-watt light bulb.

All its other parts, too, are not only of the highest precision, but also

practically wear-free. An Atmos can therefore expect to enjoy a service

life of a good 600 years, although with today's air pollution we

regrettably have to recommend a through cleaning every 20 years or so.

Admirers of advanced technology, however, aren't the only ones who get

their money's worth. Connoisseurs of elegant forms, precious materials and

traditional craftsmanship, do so as well. Because every Atmos is still

made entirely by hand; and with some models a single clock takes a whole

month to produce. Not counting the five weeks of trial and adjustment that

every Atmos has to undergo. Only then, are the Jaeger-LeCoultre

master-watchmakers happy enough with the state of things to confirm it

with a signature and allow another Atmos to leave the workshop. After

which, many end up in the very best homes, because for decades now the

world's most celebrated watch-making country has been presenting its

distinguished guests with this masterpiece of Swiss artistry.

The Atmos has had the honour to be associated with great statesmen,

royalty, and other renowned people including John F. Kennedy, Sir Winston

Churchill, General Charles De Gaulle, and Charlie Chaplin.

#<10000 early

mercury type

#10000-25000 early production run

#25000-300000 made in the 1950's and 1960's

#300000-550000 are the 1970's

More on Atmos:

1)

Louis Benjamin Audemars 1782-1833

Jean-Baptiste Baillon III (d. 1772)

As one of the leading makers of his day,

Jean-Baptiste Baillon III (d. 1772) only used the finest dials such as

this one made by Antoine-Nicolas Martinière (1706-84) and cases supplied

by the finest makers of his day such as Jean-Joseph de Saint-Germain.

Other case makers included Jean-Baptiste Osmond, Balthazar Lieutaud, the

Caffieris, Vandernasse and Edmé Roy, while Chaillou executed some of his

enamel work. Baillon was undoubtedly the most famous member of a long line

of clockmakers and one of the most significant makers of the eighteenth

century. His importance was largely due to his business acumen and the way

in which he organized a vast and thriving manufactory on an unprecedented

scale. His private factory in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, which was managed

from 1748-57 by Jean Jodin (1715-61) and continued until 1765 when Baillon

closed it, was unique in the history of eighteenth century clockmaking.

The renowned horologist, Ferdinand Berthoud was among many to be impressed

by its scale and quality and in 1753 noted "His [Baillon's] house is the

finest and richest Clock Shop. Diamonds are used not only to decorate his

Watches, but even Clocks. He has made some whose cases were small gold

boxes, decorated with diamond flowers imitating nature…His house in

Saint-Germain is a kind of factory. It is full of Workmen continually

labouring for him…for he alone makes a large proportion of the Clocks and

Watches [of Paris]". From there he supplied the most illustrious

clientele, not least the French and Spanish royal family, the Garde-Meuble

de la Couronne as well as distinguished members of Court and the cream of

Paris society.

Baillon's father, Jean-Baptiste II (d. 1757) a Parisian maître and his

grandfather, Jean-Baptiste I from Rouen were both clockmakers as was his

own son, Jean-Baptiste IV Baillon (b. 1752 d. circa 1773). Baillon himself

was received as a maître-horloger in 1727. 1738 saw his first important

appointment as Valet de Chambre-Horloger Ordinaire de la Reine. He was

then made Premier Valet de Chambre de la Reine sometime before 1748 and

subsequently Premier Valet de Chambre and Valet de Chambre-Horloger

Ordinaire de la Dauphine to Marie-Antoinette, 1770. His Parisian addresses

were appropriately Place Dauphine by 1738 and rue Dauphine after 1751.

Through his success, Jean-Baptiste Baillon amassed a huge fortune, valued

at the time of his death, 8th April 1772 at 384,000 livres. His own

collection of fine and decorative arts were auctioned on 16th June 1772,

while his remaining stock, which was valued at 55,970 livres, was put up

for sale on 23rd February 1773. The sale included 126 finished watches,

totalling 31,174 livres and 127 finished watch movements at 8,732 livres.

There were also 86 clocks, 20 clock movements, seven marquetry clock

cases, one porcelain clock case and eight bronze cases of which seven had

elephant figures totalling 14,618 livres. To give some idea of the extent

of his enterprise the watch movements had reached 4320 and clock movements

3808 in number.

Today we can admire Baillon's work in some of the world's most prestigious

collections including the Parisian Musées du Louvre, des Arts Décoratifs,

National des Techniques, de Petit Palais and Jacquemart-André. Other

examples can be found at Château de Versailles; Musée Paul Dupuy,

Toulouse; the Residenz Bamberg; Neues Schloss Bayreuth; Museum für

Kunsthandwerk, Frankfurt; the Residenzmuseum Munich and Schleissheim

Schloss. Further collections include the Musées Royaux d'Art et d'Histoire

Brussels; Patrimonio Nacional Spain; the Metropolitan Museum, New York;

Newark Museum; Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore and Dalmeny House, South

Queensferry.

Bailly (d. after 1818)

As one of the leading clockmakers during the Empire, Bailly was appointed Clockmaker to the Emperor Napoleon and was one of the main suppliers to the Imperial Garde-Meuble. He was also responsible for the maintenance of clocks at Chateau Compiegne and the Trianons, Versailles. Examples of his work can be seen at Compiegne, Fontainebleau and the Trianons as well as in notable French museums - the Louvre, Musee Marmottan, Musee de la Legion d'Honneur and the Garde-National, Paris. Pierre-Philippe Thomire, Claude Galle and others supplied very beautiful cases for his clocks.

Beefe

Gilles de

Biographie (par André Thiry) : _ Gille 1 De Beefe,

descendant d'une lignée d'habiles horlogers originaires de

Befve-lez-Thimister,. is born the 4 octobre 1694. Possédant une grande maîtrise

en horlogerie et en mécanique, en 1726, il s'installe à Liège. Le roi

du Portugal, en 1733, lui commande deux horloges avec carillons pour le

palais de Mafra. En compagnie de Jean Debefve (son cousin) qui remplaça

son frère Nicolas (pour une raison à ce jour unknowne), ils se rendent

dans cette ville pour y diriger les opérations de montage. Il fit également

le carillon de la cathédrale de Lisbonne. Le 28 september 1739 revenu

dans son pays et s'y étant perfectionné, Gille obtient du prince - évêque,

George Louis de Berghes, " un octroi exclusif pour faire et vendre au

Pays de Liège et Comté de Looz des montres à secondes, minutes, sans

roues de champ " 2. En 1740, cette invention lui vaut le titre

d'horloger de Son Altesse le Prince et en 1752, il est nommé horloger de

la cathédrale Saint-Lambert. En 1754, il conclut une convention avec le

chapitre de la cathédrale afin de construire une nouvelle horloge dotée

d'un carillon. L'ouvrage terminé est si parfait qu'il reçoit une

gratification.

Gille de Beefe est décédé le 16 september 1763; Il est donc impossible

de lui attribuer l'horloge de l'église saint Servais à Maestricht.

P; Th. R. Mestrom dans son ouvrage "Limburgse klokken en hun

Makers" Maastricht, 1997 page 82, annonce de beefe François

1718-1784, fils de Gille de Beefe comme le réalisateur de cette horloge.

La date de naissance (François) 4 december 1718, fils de Gille,

correspond avec les données de cet historien.

François, maître carillonneur - horloger à l'âge de 49 ans va

entreprendre la fabrication de l'horloge de l'église saint Servais à

Maestricht situé à 30 km de Thimister.

Le 16/08/1745, il est surveillant et réparateur des horloges des tours de

la ville. à cette époque, Maestricht faisait partie de la principauté

de Liège.

Les pièces d'horlogerie que l'on attribue à François de Beefe à

Maestricht sont postérieures à la date de sa rentrée du Portugal à

Thimister le 30/09/1739.

A titre d'anecdote : la machine à carillonner de la cathédrale saint

Lambert porte la mention "G. et N. de Beefe 1756". Lors de la révolution

liégeoise en 1794, la cathédrale Saint Lambert fut détruite. Le

carillon survécu et fut réinstallé dans le clocher de la cathédrale

Saint Paul. Il refonctionna pour la première fois le 6 august 1813 à

l'occasion du passage à Liège de l'impératrice Marie-Louise.

Certains éléments de cette biographie proviennent de messieurs Florent

Pholien (†) et Pierre Guérin.

Ferdinand Berthoud 1)

The quest for accurate timekeeping owes much to his numerous inventions, innovations and writings.

He was born in Plancemont, Switzerland, the son of an architect and judiciary. In 1741 he

began a three year apprenticeship as a clockmaker under his brother, Jean-Henri. He

subsequently went to Paris, where it is thought he studied under the eminent clockmaker,

Julien Le Roy (1686-1759). Even before he attained his mastership in 1754 he had begun

to establish great repute. In 1752 Berthoud, aged 25 was invited to present to the Académie

des Sciences a clock he had made which had a perpetual calendar and also indicated mean

and solar time. It was received with great acclaim. He made his first marine chronometer in

1754 (sent for trial in 1761) and in 1764 was appointed "Horloger Mécanicien de sa Majesté

et de la Marine ayant l'inspection de la construction des horloges Marines".

The position was of considerable importance especially at a time when the race to find longitude (and

thus a means of measuring time accurately at sea) was the social and political talk of

Europe.

From 1766 Berthoud was put in charge of designing all timepieces used on board

the French royal fleet. In the same year he was made a member of the Royal Society

London and was later appointed a Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur.

Berthoud not only made numerous complex and quality pieces but also wrote over 4000

pages on the subject. He was a great innovator whose most notable inventions included a

bimetallic compensating balance and a detent escapement. His clocks and watches have

rightly been described at the cutting edge of horological invention. His work is prized by

major private collectors and museum curators including those at the Metropolitan Museum

and Frick Collection, New York and at the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers and Mobilier

National, Paris. The Wallace Collection, London; the National Museum, Stockholm and

the Mathematische Physikalische Salon, Dresden also represent his oeuvre.

Ferdinand Berthoud

Paris. 2)

1729: born in Le Locle (Switzerland)

1745: Went to Paris to Julien LE ROY

1754: Master

1771: Horloger de la marine

1807: died

Devised the spring detent probably independently of EARNSHAW.

1759: Published: 'L'Art de régler les pendules,' .

1763: Published: 'Essai sur l'Horlogerie,'

1773: Published: 'Traité des Horloges Marines,

1773: Published: Éclaircissements sur l'Invention des Horloges Marines? .

1775: Published: 'Les Longitudes par la mesure du Temps,'

1787: Published: 'Histoire de la Mesure du Temps,'

1792: Published: 'Traité des Montres à Longitudes,'

1797: Published: 'Suite du Traité des Montres à Longitudes,'

1802: Published: 'Histoire de la mesure du Temps,'

1807: Published: 'Supplément au Traité des Montres à Longitudes,'

Clockmaker to the King and the Marine.

Membre de l'Institute F.R.S. London.

Made first chronometer 1754, sent for trial 1761.

Ferdinand Berthoud Paris. 3)

More about Berthoud:

Ferdinand Berthoud, Julien le Roy and Breguet are the three most famous names in

French clockmaking.

Berthoud was born at Plancement, commune de Couvet, caton de Neuchâtel,

Switzerland, on 19 March 1727. His father, an architect and magistrate of the

Val de Travers, had at first destined him for an ecclesiastical career, but as

at a very early age he showed interest in mechanical matters, he decided to have

him taught clockmaking. At the age of 14 Ferdinand was apprenticed to his

brother Jean Henri.

When he was 19, he borrowed 200 livres to go to Paris, where another brother,

Jean-Jaques, a designer, was already established. It is thought that he worked

for Julien Le Roy for some time, before settings up his own workshop in the rue

du Harley, not far from the house in which the latter was still working. At this

time he made the acquaintance of Piere Le Roy, who, throughout his career, was

his only rival.

In 1752 he presented to the Academy of Science an equation watch with a

perpetual calendar.

His knowledge of mathematics and physics, together with his ability to impress

the authorities with his capacities, enabled him in 1764 to obtain the office of

"Horloger de la Marine Royale" (Clockmaker toe the Royal Navy), with

an annual pension of 3000 livres, which ensured, with his other activities, An

average income of 7,500 livres a year. By order of the King, he went twice to

England, with Camus and Lalande, to examine John Harrison's marine clocks.

Although he was able to study clocks number 1, 2, and 3 Harrison refused to show

him clock number 4. After having learnt some English,, during his second

journey, in 1766, Berthoud obtained from Thomas Mudge, who, with Kendall and

Matthews, belonged to the committee responsible for examining Harrison's watch

number 4, which allowed him to enlarge his own researches. He then undertook the

construction of his own marine clocks 6 and 8, which were taken to Rochefort,

and handed over on 3 November 1768 to Eveux de Fleurieu, commanding the frigate

Isis, who, assisted by the astronomer Pingré, was to test them during a voyage

on he high seas.

The precision instruments that he invented enabled Berthoud to perfect a

rigorous experimental technique, adopted bu all his successors, and particularly

by his nephew Pierre Louis Berthoud.

He can be criticised for having sought to appropriate the important discoveries

concerning marine watches made by Pierre le Roy, his celebrated rival. However,

it would be unfair to think that Ferdinand Berthoud's considerable quantity of

work did not contribute to the progress of chronometry.

We owe to him many experimental marine watches, most of which, purchased

by the Government, are preserved in the Musée National des Techniques

(C.N.A.M.), Paris. They include watches and clockes with equation of time,

seconds watches, and superb astronomical longcase clocks fitted with compensated

pendulums which he invented. All the timepieces that he made show his great

dexterity, and the exceptional quality of his execution.

He left many documents on clockmaking, printed at State expense, in which his

experiments and intentions are described in great detail. From a small pamphlet,

published in 1759 under title L'art de coduire et r´´gler lres pendules et

les montres à l'usage de cuex qui n'ont aucune connaissance d'horogerie,

which went into six editions between 1759 and 1836, without counting Henri

Robert's edition of 1841 and the numerous translations into different languages,

to his Supplement au traité des horloges marines...published in the year

of his death 1807, the written work of Ferdinand Berthoud covers more than 400

pages, illustrated by over 120 plates, engraved from drawings by the author.

He died on 20 June 1807, in his property at Groslay, near Montmorency, leaving

no children. He married twice, firstly Mademoiselle Chati of Cean, and then

Mademoiselle Dumoustier of Saint Quentin.

Ferdinand Berthoud was appointed, in succession, Clockmaker to the Navy, Member

of the Institute of France, Fellow of the Royal Society of London, and Chevalier

of the Légion d'Honneur. The State paid him an annual pension of 3000 livres

until the day of his death. His name figures among those of great men engraved

on the facade of the Palace of Industry.

His chief pupils were Jacques and Vincent Martin, and particularly his nephew

Pierre Louis Berthoud.

Pierre Louis Berthoud

Pierre-Louis Berthoud (1754-1813), known as Louis was a very important clockmaker and an ingenious scientist. His father, Pierre was a clockmaker but Louis trained under his highly esteemed uncle, Ferdinand Berthoud (1727-1807) and later succeeded Ferdinand’s business. Like his uncle, Louis was particularly interested in precision horology specialising in making regulators, over 150 chronometers as well as clocks and watches. He was appointed as clockmaker to the Observatoire and to the Bureau de Longitude. He won a gold medal at the Paris Exposition, l’an X (1800/1) and wrote ‘Entretiens sur l’horlogerie”.

Jean Simon Bourdier

JEAN-SIMON BOURDIER (c. 1760-1839)

One of the most innovative clockmakers of his time, Jean-Simon Bourdier became a maitre horloger in Paris on 22 September 1787. He is recorded as working in the rue des Precheurs in 1787, quai de 1'Horloge du Palais circa 1790, rue Mazarine in 1801, rue Saint-Saveur in 1812 and rue Saint-Denis in 1830. He gained a silver medal in the 1806 and 1879 produits de I'industrie exhibitions.

He is known to have worked with the ebenistes Lieutaud and Riesener as well as the bronziers Galle, Thomire and Remond. his dials were painted by the emailleurs Dubuisson and Coteau. His clocks were also sold by the dealers Daguerre -and Lignereux and

Juilliot.

Abraham Louis Breguet 1754-1823 Breguet

1747: born at Neuchatel, 1823:

died

Started in Paris 1776, but watch No. 1 is of 1787. Breguet attracted the

attention of Louis XV and set up in Paris on the quai de l'Horloge. He

became a member of the Academy des Science. Very soon Kings, Princes and

European celebrities were buying his watches. Breguet made the first

"perfect&hibar; automatic watch, capable of running for eight years

without being overhauled and without going slow. This watch still keeps

perfect time today. Breguet's inventions meant that it was possible from

then on to make watches accurate to within a tenth of a second. Thanks to

him, considerable progress was made in marine navigation, astronomy and

physics, and his contemporaries began to look at the time in the way you

look at a jewel. Breguet signed his watches in the way that Boulle signed

his furniture and Rembrandt his paintings.

The extra-flat watch was one of Breguet's inventions. The perpetual or

automatic watch, the perfecting of so-called "multiple complication"

watches, the balance spring, were all Breguet. The "tact" watch, the

constant-force escapement and the tourbillon watch were also by him. It

would take hours to list all his inventions. Many watches bearing his name

were made outside and finished in his workshop. There are innumerable

watches being his name in forgery. He made many improvements, including

the parachute ca.1790, and the tourbillon in 1801, also many self-winding

watches. He was the first to make lever escapement with lift partly on the

pallets and partly on the teeth. The overcoil balance spring is known by

his name. Draw was absent from early levers, but used after 1814.

Most important collections contain genuine and forged watches. The late

Sir David Salomons had a collection of 102 watches and 6 clocks by

Breguet.

Subscription watches: British Museum, London, Guildhall Museum. British

Science Museum, S. Kensington

Striking cylinder watch and musical. repetition. cylinder watch: British

Science Museum.S. Kensington

Tourbillon watches: Guildhall Museum and Ilbert collection. The latter, of

1808, was the first made.

Verge watch: Dennison collection.

Pedometer winding repetition watch No. 27 (1791), several watches and

pedometer: Ilbert collection,

Regulators: Buckingham Palace and Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers, Paris

|

Cabinet. A small workshop in eighteenth and nineteenth-century Geneva, on the top floor of a house where there was the most natural light. Cabinotier. A workman employed by a cabinet. A cabinotier was not necessarily a watchmaker. He could be a jeweller, engraver, stonecutter, etc., provided he worked for a cabinet and was employed in watchmaking. |

|

Jacques Caffieri (1678-1755) was the tenth son of Phillippe Caffieri [1634-1716], who emigrated from Naples at the request of Cardinal Mazarin to decorate the interiors at Versailles. He was elected to the Académie de Sainte-Luc as a sculptor, and thus created many of the original designs that were proprietary models of his foundry. From 1736, when he was appointed fondeur-ciseleur des Bâtiments du Roi, Caffieri remained in the employ of the French Crown. His most famous work is the large astronomical clock, its movement designed by Passemont and made by Dauthiau, which was completed in 1753 for the Cabinet de la Pendule at Versailles. Pierre Verlet notes that Caffieri typically signed bronzes destined for the French Crown.

More on Caffieri: 1) 2)

C couronné, Control stamp on French bronzes. The "C" stands for copper (cuivre), and this stamp was used on alloys containing copper to denote that a tax had been paid between 1745 and 1749.

Pierre A. Caron 1732-1799

An enamelling technique in which the outline of the subject is formed by thin flat metal wires set on the surface to be enamelled to form cells. These cells are filled with enamel and fired. After polishing, the wires bring out the subject or pattern that is set in the enamel. Cloisonné is used to describe both the technique and the end result.

James Ferguson Cole 1799-1880

Salomon

Coster.

Salomon Coster, a famous Dutch maker born in Haarlem before 1623, moved to

The Hague shortly after his marriage in 1643. Like several Haarlem

clockmakers, he was an Anabaptist. In 1646 Pieter Visbagh was apprenticed

to him for six years, and in 1657 Christiaan Reijnaert for ten years. In

the same year Christiaan Huygens allowed him ('met privilege') to make and

sell pendulum clocks. In this year John Fromanteel came from London and

worked with Coster for at least eight months, but probably much longer,

followed by Nicolas Hanet from Paris in 1658. Salomon Coster died suddenly

in December of 1659 and the following year the shop was taken over from

Coster’s widow by Pieter Visbagh.

Ref: Dr. R. Plomp, Spring driven Dutch pendulum clocks 1657-1710.

Joseph Coteau

JOSEPH COTEAU (1740-1801) Joseph Coteau was born in 1740, probably in Geneva and died in Paris on 21 January 1801. He became maitre-pintre-emailleur at the Academic de Saint-Luc in Geneva on 6 November 1766 and was installed in rue Poupee, Paris by 1772. Coteau is celebrated not only for his skill in decorating enamelled dials but also as a skilled miniaturist. He discovered a new method for fixing raised gold on porcelain and worked closely with the Sevres manufactory in developing their so-called "jewelled" porcelain.

A cycloid is the curve defined by the path of a point on the edge of a circular wheel as the wheel rolls along a straight line. It is an example of a roulette, a curve generated by a curve rolling on another curve.

Edward John Dent 1790-1853

Dubuisson

Gobin Etienne,

(b. 1731 d. after 1815)

known as Dubuisson, who with Coteau was the finest of his

trade. After living in Luneville and Strasbourg, Dubuisson worked at

Chantilly. In 1756 he was employed at Sevres as a flower painter, specialising in enamelling watch cases and clock

dials.

John Ellicot 1706-1772

Josiah Emery 1725-1797

Thomas Earnshaw 1749-1829

Equation of Time

Along with the transition from telling time with sundials to telling time

with clocks, people realized that the time from one noon to the next was

not constant. Part of the jargon invented to deal with the situation is

"sun time", the time a sundial would tell, and "mean time", the time an

accurate clock would tell. The difference between the two is an error that

has come to be called the "Equation of Time". It is usually described as a

table, plotted as the error vs. the Sun's declination, or plotted a graph

of error vs. date:

See full equation

table.

See

today's equation.

Equation Table

by Claude Raillard a Paris 1718.

(master 1691, d.1762)

Admiral Fitzroy

1805-1865

1) ADMIRAL ROBERT FITZROY

(By Charles Edwin inc.)

Robert Fitzroy, son of Lord Charles, was born at Ampton Hall, Suffolk, in

1805 and entered the Navy at the age of 12. During his long career, he was

for many years Captain of the HMS Beagle which achieved fame as a result of

Charles Darwin's expeditions. He eventually rose to the rank of Admiral, was

elected Member of Parliament for Durham in 1841, and appointed Governor of

New Zealand in 1843.

At his retirement from active service in 1850, he turned his attention to

the science of meteorology. Among his considerable accomplishments, he

induced the Times to print weather information on a daily basis and the

Board of Trade to supply many coastal villages with barometers. He designed

a vastly improved marine barometer.

In 1862 he published his Weather Book

which summarized his extensive and immensely important work on meteorology.

To the barometer collector, he is most remembered for consolidating weather

information and presenting his now classic Remarks, which distinguish the

barometer carrying his name, that interpret the meaning of rising or falling

mercury. He coined a useful phrase which is as good today as it was then:

"Long foretold - Long Last Short notice - Soon Past"

Admiral Fitzroy's Barometers were not designed by and were probably never

seen by Admiral Fitzroy who took his own life in 1865 before the earliest

known Fitzroys were made.

ADMIRAL FITZROY'S BAROMETER

By far the best known type of barometer ever produced was called Admiral

Fitzroy's Barometer and was the first inexpensive and serviceable barometer

made by mass-production methods. The earliest Fitzroys were made in the late

1860s, so it is probable that Fitzroy himself, who died by his own hand in

1865, never saw one.

Common to these large late-19th century instruments is the degree of

detailed information concerning not only the rise and fall of pressure, but

of associated conditions of temperature and direction of the wind. His

remarks, carried on most barometers, emphasize the fact that the state of

the air, as shown by the barometer, tells coming rather than present weather

conditions.

Typical ancillary instruments include a Fahrenheit thermometer and a storm

glass. Storm glasses have been known since the 17th century but came into

general use with the Fitzroy barometer. Clamped onto the lower left, these

are glass cylinders with brass caps. The contents are a mixture of camphor,

ammonia, alcohol, potassium nitrate, and water, which reacts to air

pressure, wind direction, and electrical charge of the air.

Typical readings and the predicted weather:

Clear liquid . . . . Good, fine weather

Crystals at bottom . . . . Frost in winter

Turbid liquid (substance rising) . . Rain

Turbid liquid with crystals. . . . Thunder

Large crystals. . . . Close weather, cloudy skies, snow

Chains of crystals at the top . . . . Windy weather

Substance lies to one side . . . . Storm or wind from other direction

Copyright 1996-1999 © by Charles Edwin Inc.

2) About ADMIRAL

FITZROY

Admiral Robert Fitzroy was one of the first to attempt a scientific weather

forecast, introducing the first daily weather forecasts which were published

in The Times in 1860. He began his career in the navy and was famous for

choosing Charles Darwin as a companion during the voyage on the Beagle. As a

sailor, Fitzroy had always been aware of the importance of forecasting the

weather.

Once he had completed his famous journey, he took up the newly created post

of Head of Meteorology at the Board of Trade (the Met Office) and began to

collate the information necessary to predict the weather. Using the newly

invented electric telegraph, Fitzroy managed to receive data quickly enough

to make a forecast viable.

Fitzroy's name was associated with several different types of barometers,

though whether he could be called the inventor of all of them is

questionable.

One version of the barometer of which he was responsible for the designing

and distribution, was used by sailors prior to sailing. Fitzroy advocated

placing a barometer at every port so that seamen could read them before

embarking on their journeys. Decisions on whether to sail or not were able

to be made based on the level of the mercury within the instrument, saving

many lives.

The Fitzroy barometers were enormously popular, both because of their ease

of use and their association with the highly respected Admiral Fitzroy. This

interest continued into the twentieth century.

Some of the components added onto the Fitzroy Barometers included bottle

tubes, storm glasses, thermometers and Fitzroy's instructions for

interpreting the results.

Unfortunately Admiral Robert Fitzroy never felt completely satisfied by his

achievements. Though he had saved many lives by his advances in forecasting

the weather, he had a conflict with his conscience and his religious

beliefs. This he never resolved in life and at the age of sixty he committed

suicide by cutting his throat.

Picture of Fitzroy

barometer

Charles Frodsham 1810-1871

William Frodsham 1778-1850

Georg Graham 1673-1751

Gregorian calendar ( calendrier grégorien )

The calendar introduced by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 to reform the Julian calendar. The majority of countries refer to the Gregorian calendar. It has 365¼ days. A non-leap year has 7 months each with 31 days, 4 months with 30 days, and 1 month with 28 days (29 days in a leap year). It is a solar calendar, based on the movement of the sun.

Under the Julian

calendar, the year was 11 minutes and 14 seconds longer than the solar

year. By 1582 the accumulated difference came to 10 days. The Gregorian

calendar introduced the following system: each year that can be divided by

four is a leap year.

Century years are leap years only if they are evenly divisible by four

hundred. Hence 1700, 1800 and 1900 were not leap years whereas 2000 was.

1582: On Friday October 15th (which came after Thursday October 4th in the Julian Calendar), Italy, Spain, Portugal, France and the Catholic Dutch provinces implemented the Gregorian Calendar, introduced by Pope Gregory XIII.

1584: Austria, Germany and Catholic Switzerland.

1586: Poland.

1587: Hungary.

1610: Prussia.

1648: Alsace (Strasbourg in 1682 following its annexation by France).

1700: Germany, Switzerland, the Protestant Dutch provinces, Denmark and Norway.

1752: Adopted by England, its American colonies, and Sweden.

1753: Protestant Switzerland (the last canton being Grisons, in 1811).

1873: Japan replaced the Chinese lunar calendar with the Gregorian calendar.

1912: China took the Gregorian calendar as its official calendar

1916: Bulgaria.

1923: Greece, USSR (the October Revolution of 1917, which marked the start of the Russian Revolution, was in November of the Gregorian Calendar).

1919: Rumania and Yugoslavia.

1926: Turkey.

The monasteries of

Mount Athos (Macedonia) still use the Julian Calendar.

Henry Grandjean 1774-1845

Hamilton Watches 1892 Brief History of the Hamilton Watch Company.

Although the Hamilton Watch Company opened in December of 1892, they spent

over a year "gearing up" without producing a watch. Their start of

production was March of 1894. The only watches they produced were pocket

watches, most notably their reliable railroad watches.

In 1908, they started making ladies pendant watches which were much

smaller than the large pocket watches produced until then. Ladies

wristwatches were introduced after World War I. They were a re styling of

the pendant watches, and had cloth or ribbon straps.

Men's wristwatches were considered effeminent prior to the 1920's.

Hamilton introduced their first men's "strap watch" on November 11, 1922.

They had to not only market the watch, but they had to market the "idea"

of a strap or wrist watch. Finally, their use in hot summers when vests

were not worn, the association with the war, explorers, and rugged outdoor

activities all helped the wristwatch gain acceptance. Hamilton was out in

front selling the idea, and aimed much of their promotional materials at

merchants--how to sell the "idea."

In the late twenties, they introduced some stylish watches like the

"Cushion," "Square," and the "Tonneau." Their art deco designs of the

1930's were accompanied with the practice of naming all of the watches.

Many people think the 1930's designs were the golden age of Hamilton's

design and production.

World War II saw the halt of consumer production to concentrate on

military watches. Following the war, they sold pre-war designs. Hamilton

had introduced new designs in the early 1950's. By the mid 50's, their

styling failed to capture the American public.

In 1957, they introduced the world's first electric watch--the Ventura.

With a radical asymmetric design to accompany the radical technology, it

became Hamilton's best ever selling gold watch. Many think that the superb

manual movements of the 1930's through the 1950's, and the innovative

electric watch, make Hamilton the most influential watch company of the

century.

They are still producing

watches today, but the brand name is now owned by the Swatch Group. They

last produced watches under their own original company in 1969.

hamilton watches

dates

John Harrison 1693-1776

Jaques Frederic Houriet 1743-1830

Pierre Frederic Ingold 1787-1878

Temporal hours.

Japanese traditional timekeeping practices

(profoundly influenced by chinese horometry) required

the use of unequal

temporal hours: six daytime units from local sunrise to local sunset, and six

night time units from sunset to sunrise. As such, Japanese timekeepers varied

with the seasons; the daylight hours were longer in summer and shorter in

winter, and vice versa. European mechanical clocks were by contrast set up to

tell equal hours that did not vary with the seasons.

Most Japanese clocks were driven by weights; however, the Japanese were also

aware of, and occasionally made, clocks that ran from springs. Like the Western

lantern clocks that inspired their design, the weight driven clocks were often

held up by specially built tables or shelves that allowed the weights to drop

beneath them. Spring driven Japanese clocks were made for portability; the

smallest were the size of large watches, and carried by their owners in inro

pouches.

|

Daily time to rewind and set

clocks (with a sundial) Midday. |

||

|

Sunrise. |

|

Sunset. |

|

Midnight. Each hour (toki) was divided into 10 'bu'. |

The traditional Japanese

time system.

The typical clock had six numbered hours from 9 to

4, which counted backwards from noon until midnight; the hour numbers 1 through

3 were not used in Japan for religious reasons, because these numbers of strokes

were used by Buddhists to call to prayer. The count ran backwards because the

earliest Japanese artificial timekeepers used the burning of incense to count

down the time. Dawn and dusk were therefore both marked as the sixth hour in the

Japanese timekeeping system.

In addition to the numbered temporal hours, each hour was assigned a sign from

the Japanese zodiac.

Starting at dawn, the six daytime hours were:

|

Zodiac sign |

Zodiac symbol |

Strike |

|||

|

卯 |

六 |

6 |

6 | ||

|

辰 |

五 |

5 |

|

8 | |

|

巳 |

四 |

4 |

|

10 | |

|

午 |

九 |

9 |

12 | ||

|

未 |

八 |

8 |

|

14 | |

|

申 |

七 |

7 |

|

16 |

From dusk, the six nighttime hours were:

|

Zodiac sign |

Zodiac symbol |

Japanese numeral |

Strike |

Solar time |

|

|

酉 |

六 |

6 |

18 | ||

|

戌 |

五 |

5 |

|

20 | |

|

亥 |

四 |

4 |

|

22 | |

|

子 |

九 |

9 |

24 | ||

|

丑 |

八 |

8 |

|

2 | |

|

寅 |

七 |

7 |

|

4 |

The Meiji Restoration

(1868-1912) marked the beginning of the rapid modernization of Japan as it

strove to "catch up" to the Western powers which it had fallen behind in

technological and social development. Public education was instituted in 1872,

as was the western Gregorian

solar* calendar with its 'equal hours' system of timekeeping

(1 jan. 1873). It sparked a renewed interest in time

keeping.

Japan's first mass production clock factory, Kingensha, was established in 1875. In 1892,

Kintaro Hattori founded Seikosha (later know as Seiko), which remains a

cornerstone of Japanese timepiece production to this day.

* the lunar calendar was abolished.

More:

1)

Pierre Jaquet-Droz

1)

Pierre Jaquet-Droz was bom at La Chaux-de-Fonds in 1721 and died in Bienne in 1790. He was one of the most brilliant and innovative clockmakers of his era. His company specialised in musical and automaton clocks, boxes, fans, singing birds and all manner of ingenious play-toys. He journeyed throughout the whole world including England, France and Spain. In Madrid he was condemned to death by the

inquisition for allegedly, practicing black magic but was saved by the Bishop of Toledo. During the latter part of his life he took his adopted son, J.F. Leschot into business and the company continued to prosper until after his death.

Jaquet Droz made a number of organ clocks.

2)

Pierre

Jacquet Droz 1721-1790

Juno was worshipped as protectress of women especially in marriage and childbirth. According to mythology she was the chief goddess of Olympus and both sister and wife of Jupiter. Here we see Cupid holding her girdle. This magic belt, borrowed from Venus was intended to make anyone that wore it irresistibly desirable - which Juno needed to attract the attention of her faithless husband, Jupiter. She also carries a sceptre, which like the peacock was another other attributes. In the "Golden Ass", Apuleius told the story of how Juno sent Argus, a giant with 100 eyes to watch over lo. Mercury then killed Argus, so in his memory Juno placed his eyes onto the tail of her peacock.

1) Jørgen Jørgensen

Jürgen Jürgensen Founder of the dynasty, born in 1745.

He began his apprenticeship in Kobenhavn in 1759 and finished it in 1765.

In 1766 he started a big tour through Germany and Switzerland. He took

this opportunity to change his name to Jürgen Jürgensen. Finally he

reached Geneva and Le Locle. There he found work in J. F. Houriet's

factory. Later he became the latter's agent for Scandinavia. Returning to

Kobenhavn, he founded his own workshop and a watchmaking factory together

with Isaak Larpent in 1773. He married Anna Leth Bruun in 1775. Two of his

children became watchmakers. He was finally appointed watchmaker to the

Danish court in 1785.

He died in 1811.

2) Urban Son of Jürgen, born in 1776.

After his school years he did his apprenticeship with his father,

beginning in 1790. In 1795 his father sent him on a tour to Switzerland,

specifically to Le Locle and Geneva. After 2 years there, he moved to

Paris, where he met Breguet and F. Berthoud, and then to London, to meet

Arnold, all this sponsored by the Danish State. He travelled home via

Paris, Le Locle, where he married the daughter of J. F. Houriet, and

Geneva. By the end of 1801 we find him back in Kobenhavn working together

with his father. In 1804 he published his first book (see Bibliography).

From 1807 - 1809 he travelled again to Le Locle, to visit his relatives,

and to Geneva, to learn jewelling for horological purposes. After the

death of his father, in 1811, he opened his own business. He signed "Urban

Juergensen". In 1815 he was elected as a member of the Royal Philosophic

Society, in 1822 he was appointed "maker" to the Admiralty, and in 1815

knight of the order of the Danebrog. Two of his children became

watchmakers.

He died in 1830.

Please note: Wherever Urban writes Neuchâtel in his autobiography, he

means the county. The town he went to was Le Locle, because J. F. Houriet

lived there.

3) Frederik Son of Jürgen, born in 1787.

He was 11 years younger than his brother. After school he also did his

apprenticeship in the workshop of his father but was taught by Urban. 1811

we meet him in Le Locle visiting his brother's relatives and working

there. At the time of his father's death he still stayed in Switzerland.

Called back to Kopenhagen his brother more or less forced him to take over

the parental workshop as well as the factory and to run it together with

and for his mother. So from 1811 onwards the signature "Larpent &

Juergensen" was changed in "Frederik Juergensen". For this Urban reached

for him to hold an appointment as a watchmaker to the Danish court in

1811. The same year he married. After the birth of a daughter in 1813 the

son Georg Urban, also called Fritz, was born in 1818. Things were not

going bad but Frederik was of a rather poor health. So the last years of

his life he made big efforts to pave the ways for his son to keep the

horological production going on.

He died in 1843.

4) Louis Urban Son of Urban, born in 1806, died in 1867

5) Jules Frederik,

known as Jules Son of Urban, born in 1808, died in 1877

6) Georg Urban Frederik,

known as Fritz Son of Frederik, born in 1818, died in 1863

7) Urban August Son of Louis Urban, born in 1836, died in 1866

8) Jules Urban Frédéric,

known as Jules II Son of Jules, born in 1837, died in 1894

9) Jaques Alfred Son of Jules, born in 1842, died in 1912

A device similar to the tourbillon, the difference being that the cage is driven by the third wheel. Invented by Bonnicksen, a Danish watchmaker established in London.

Excerpt of a talk on ‘Traditional Brass Lacquering’ by Francis Brodie who has worked in Dan Parkes workshops and also for several museums. Francis demonstrated by deftly and very thinly lacquering some polished brass tubes. Aided by a small heat gun, the lacquer dried almost instantly before further coats were applied. Various lacquers, which had all been pre-mixed according to old recipes, were applied to tubes and also to a flat sheet of polished brass. The main possible advantage of a thin lacquer is that many coats can be applied, building up to the colour and thickness required, also this would lessen the chance of any part of the surface being missed.

Two of the recipes used for the demonstration were as follows:

| Philosophical Instrument Lacquer: | ||

|

Gum

Sandarac Gum Elemi Dragons Blood Shellac Saffron Spirits of Wine |

8

oz. 8 oz. 8 oz. 4 oz. 3 oz. 1 pint |

226.8 gram 226.8 gram 226.8 gram 113.4 gram 85.05 gram 0.568 liter |

| Gold lacquer: | ||

|

Shellac Turmeric Dragons Blood Spirits of Wine |

4

oz. 1 oz. ¼oz. 1 pint |

113.4 gram 28.35 gram 7.09 gram 0.568 liter |

Francis recommended that

a good substitute for Spirits of Wine is isopropyl alcohol. Many of the

other ingredients used are still available, but may be a little harder

to find these days.

Lange Glashutte Manufacturing dates

Antoine Lechaud 1812-1875

Balthazar Lieutaud ebiniste

BALTHAZAR. LIEUTAUD (circa 1720-1780) Balthazar Lieutaud became a maitre in 1749. The son of the ebeniste Charles Lieutaud and grandson of Francois Lieutaud an ebeniste from Marseilles, he specialized in clockcases. He worked with the bronziers Philippe Caffieri, Charles Grirnpelle and Edme Roye. By 1750 he was installed in rue de la Pelleterie on the ile de la cite, the clockmakers' district and moved to the rue d'Enfer in 1772. Following his death in 1780, his wife, Nicole Godard (1721-1800), continued to run the atelier.

Jean-Joseph Lepaute

Jean-Joseph

Lepaute, 1769-1846, was the great nephew of the founder of the Lepaute dynasty Jean-Andre

Lepaute, 1720-1789.

Jean-Joseph joined the Company as junior partner to Pierre-Basil Lepaute who was the son of Jean-Andre's brother

Joseph. The partnership was perhaps the most fruitful of them all and together they made a great number of pieces for the Chateaux of the

Tuilleries, St. Cloud, Trianon and Fontainebleau. In 1811 the firm divided and Pierre-Basil formed his own firm with his son Pierre-Michel under the name of Lepaute

Fils.

Jean-Joseph Lepaute later took on Augustin-Michel Henry who was the son of Pierre Henry who had married Jean-Andre Lepaute's sister

Elizabeth. Pierre later changed his name to Henry Neveu Lepaute and married

Annais, the daughter of Jean-Joseph.

The Lepaute dynasty continued but the present clock is a remarkable achievement of best quality clockmaking and the very highest quality

case-work.

Jean André le Paute 1720-1789

Jean-Antoine Lepine

LÉPINE Jean Antoine, son of Jean. Paris (Place Dauphine), b.1720, d.1814.

He was bom in Switzerland in a village

called Challex near Geneva. He started his horological career in Geneva

but soon went to Paris in 1744 as apprentice to Andre Charles Caron, the

King's clockmaker. He married Caron's daughter in 1756 and was made Master

in 1765 about which time he was appointed Horloger du Roi.

Lepine was responsible for a great many inventions but none more important

than a new calibre of watch movement that revolutionized watch making and

with which his name is synonymous. This 'Lepine calibre,' in which

separate bars were used instead of a single top plate was introduced about

1760.

Introduced the use of a mainspring barrel supported at one end only, and other changes, leading, with cyl. escapement, to thin watches. Described a repeating movement using rack in place of chain, in Mémbre de l'Acadademy des Science in 1766.

Watchmaker to: Louis XV, Louis XVI and Napoleon I.

Invented the virgule escapement and a keyless winding.

Acted as agent for Voltaire's workshops at Ferney ca.1770.

4-colour g. watch: Victoria and Albert Museum. S. Kensington

Enamelled watch and chatelaine: Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge,

Six watches: Guildhall Museum

Two with virgule escapement: Collection of the late Major Chamberlaine

4-colour gold watch Fränkel coll.Lyre watch: Basle Museum

Gold enamelled watches: M.P.S. Dresden. Watch Carnegie Museum

Two 4-colour gold watches: National Museum Stockholm,

Watch in porcelain case: Gélis coll.Watch in ring: Ilbert coll.

Astro. clock and three mantel clocks: Buckingham Palace, London

Two clocks: Palais de Compiègne, one made for Napoleon.Clock made for Josephine, Mobilier National, Paris

An eminent maker. He worked as CARON ET LEPINE till 1769. Left

his business to his son-in-law RAGUET in 1783.

Lepine's business was sold in 1810 to J. B. CHAPUY, who employed Jacques Lepine. It was sold in 1827 to DESCHAMP, who was succeeded in 1832 by FABRE. The business continued under the name Lépine till ca.1916.

Jean Frederic Leschot 1746-1824

Georg Auguste Leschot 1800-1884

Sylvain Jean Mairet 1805-1890

Antoine-Nicolas Martinière b.1706 d.1784

Martinière was a

remarkable inventor and enamellist, whose talents so impressed King Louis XV

that he was appointed Emailleur et Pensioneur du Roi. Martinière was the first

enameller to create a complete single enamel dial. Because of the fragile,

volatile nature of enamel, prior to this complete enamelled dials had been

restricted to watches. By the late seventeenth century clock dials featured

separate enamel plaques to display the hours, then followed an attempt to create

complete dials out of 13 or 25 individual pieces which were fitted together to

form a seemingly smooth surface. This was to change, thanks to Martinière's

dramatic technical advances circa 1740.

His unprecedented advance is best summed up in his own words, which

appeared in 1740 in 'Mercure de France'. In his 'Lettre écrite de Paris à

un horloger de Province sur les Cadrans d'Email', Martinière wrote

"You

ask me, Sir, to find out from the Porcelain Manufacturers if they could

make you a Clock Dial one foot in diameter, because you tell me that you

know it is impossible to make any of this size all in enamel, like Watch

Dials. It is true that until recently this was impossible in the City, and

even at Court: here is an example. The King ordered a Clock, and His Majesty

wished that the Dial be all of one piece, in enamel, and 14 inches in

diameter. The one who received the order could only reply that he would

attempt to carry it out, not that he would succeed.

The Sr Martinière, Enameller,

in the rue Dauphine, undertook this task, and succeeded so well in all

respects, that he had the honour of presenting it himself to His Majesty,

who was agreeably surprised, and gave him signs of satisfaction with so

much kindness that he returned to Paris, enchanted with so happy a

success, and resolved to carry out

new studies in order to advance as much in his Art as would be

possible..."

It was probably at this time that the King granted Martiniere

a pension and the title of Emailleur et Pensioneur du Roi. Louis XV, whose

interest in horology extended beyond the realms of a collector but also as

a benefactor, rewarded certain craftsmen of outstanding talent.

Antoine Nicolas belonged to a family of enamelers that included not only

his father, described by the 'Mercure' as an "able" enameler, but also his

two brothers and three cousins. Martinière and his wife, Geneviève Larsé

had one son, Jacques-Nicolas (b. 1738) who became a clockmaker. At the

time of his son’s birth the Martinières were living in rue Haute des

Ursins. By 1740 Martinière was established at the sign of the ‘Cadran

d’Email’ in rue Dauphine and then from 1741-55 in rue des Cinq Diamants in

the parish of Saint-Jacques de la Boucherie.

More on

Martinière:

1)

2)

3)

Note: later fine dial makers

were: Dubuisson, Elie Barbezat, Edme-Portail Barbichon, Jean-Antoine Cave,

Georges-Adrien Merlet and Joseph Coteau.

Marcwick

Markham

James Markwick jr. became free of the Clockmakers' Company in 1692 and died in 1730. His father's business succeeded that of Samuel Betts, one of the great early clockmaking pioneers. Markwick jr. became Master in 1720 and went into partnership with his brother-in-law Robert Markham who succeeded him in the business and carried on trading under the name Markwick Markham. Towards the end of the 18th. century the company made a large number of clocks and watches for the Turkish and Chinese markets. In fact the business was so successful that their name became synonymous with this type of clock.

Over a period of time the company associated themselves with a number of other clockmakers; Henry Borrell, 1794-1840, seems to have had a fruitful relationship with the company which is listed as ending in 1813.

Georges-Adrien

Merlet

(illustrated in Jean-Dominique Augarde, “Les Ouvriers du Temps”, 1996, p.

17, pl. 4). Merlet was one of the finest enamellers to specialise in the

decoration of clock dials. Like Coteau and Dubuisson he gained renown

during the last quarter of the eighteenth century for highly ornamented

dials and enamelled clocks.

Louis Moinert 1758-1853

Thomas Mudge 1715-1794

A system, patented in 1808 by John Schmidt of St Mary Axe, that uses transparent crystal discs with serrated edges to carry the hands. These wheels are driven by pinions, concealed inside the case frame. Generally the movement is housed in a clock’s ornamental base.

The magician and illusionist Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin (1805-1871) is also acknowledged as one of the inventors of the mysterious clock.

Ulysse Nardin 1823-1876

Niderviller porcelain active:1754 -present

Niderviller

Porcelain Manufactory

In the mid-1700s, porcelain became so popular among the nobility that

aristocrats began sponsoring their own manufactories. Jean-Louis Beyerlé,

an advisor to the king, founded one such operation at Niderviller in 1748,

developing it out of an earlier faience-making business. The new

enterprise initially drew its workers and stylistic inspiration from a

neighboring concern in Strasbourg, which produced ceramic wares in the

Rococo taste. At Niderviller, the workers modified the bright Strasbourg

palette, making it softer.

Because of its unique location in the duchy of Lorraine—where it was

exempt from French laws designed to protect the royal monopoly of the

Sèvres porcelain manufactory—Niderviller flourished for nearly twenty

years, unlike other French porcelain manufactories. When the Duke of

Lorraine died in 1766, the territory reverted back to the French crown,

and the manufactory was then subject to new, even tighter restrictions on

production and decoration. In 1772 Beyerlé sold the factory to a French

count.

An enamel-like alloy of lead, copper, silver, sulphur and sal ammoniac (ammonium chloride). Niello paste is applied over incised gold or silver then fired in the enamellist’s furnace. Excess niello is filed off and the surface smoothed. Polished niello cases were fashionable shortly before wristwatches were introduced.

The word is of French derivation and should be spelt ormoulu. It means gold ground to a powder for amalgamation with mercury The preparation was applied with a brush to the metal which was then heat treated to vaporise the mercury. The object was then burnished. Ormolu is now understood to refer to brass castings which have been gilt and are used as decoration on clock cases, furniture, and also complete articles such as clock cases, lamp stands etc.

Jacques Panier

Jacques Panier (d. Paris 1737) had become a maître-horloger by 1701 and was also appointed Huissier Chambellan du Rol. By 1701 he was established at Rue des Boucheries-Saint-Germam and then by 1734 had moved to Rue de la Verrerie. He was one of the more important Parisian makers, supplying many of the French aristocracy including the Comte de Toulouse, the Ducs de Villeroy, de Brissac, de Lauragais, de Brancas and de Mazarin. Examples of his work can now be found in the Museum of Decorative Art, Prague and at the Palazzo di Quirinale, Rome.

Albert

Pellaton-Favre (1834-1914)

1) A native of Le Locle, was one of the principle

constructors of tourbillons. He made no fewer than 82 tourbillon watches,

mostly with spring detent escapement, and won prizes from the Geneva and

Neuchatel Observatories. He was the father of James Pellaton, director of

the Le Locle Technicum, and a fine horologer in his own right.

2) The Pellatons & Patek Philipe.

Only the over 35 Tourbillons, which Albert Pellaton-Favre (1832-1914) and

his son James Pellaton manufactured for Patek Philippe, is a special class

in the area of precision horology. Apart from the outstanding results,

obtained by these calibres, it is the esthetical concept combined with the

absolute technical perfection and craftsmanship, which distinguished these

instruments. The Tourbillons of Pellaton represent the best, ever brought

out by the Swiss chronometry. The basic calibre was developed by

A.Pellaton Favre. He used, without exception, an Earnshaw chronometer

escapement in his revolving carriages. His son James Pellaton 1873 -1954),

director of the Technicum Le Locle, manufactured these Tourbillons as free

co-worker for Patek Philippe. Unlike his father he favoured however Swiss

anchor escapements. He often supplied just the complete ébauche (movement

blank) and monitored the completion of the chronometer in house, where he

had his own workbench. Exceptional performances could be obtained through

these extraordinary privileges as granted by Patek Philipe. Their reputation was established by

their farsighted and scientifically oriented way of acting. Although J.

Pellaton pursued just a concept, it became increasingly matured. Tiny

details, like the perfection of the polish or the golden scale for the

adjusting needle, which also served as a counter balance, are from an

unequalled constructional genius, which one finds only in these works. It

set thereby a standard, on which others were measured. Since regulation of

a chronometer begins with its design and construction, it was also due to

the Pellatons that these chronometers scored top results in the hands of

experienced regulators. A fact often and painfully neglected by other

manufacturers.

James Casar

Pellaton

During the 1920s and 1930s

James Casar Pellaton was the most esteemed maker of

tourbillon carriages, which he supplied to the most prestigious

companies including Patek Philippe, Vacheron Constantin, Girard-Perregaux,

.and Ulysse Nardin. The watch is described and illustrated in details in

"Le Tourbillon" by Reinhard Meis, Les Editions de l'amateur, Paris, 1990,

pp. 170-71.James Casar Pellaton (d.1954).One of the most esteemed makers

of tourbillons in the 20th century. He learned his craft from his father,

also an esteemed tourbillon maker. In terms of design, he followed his

father's footsteps, using the same type of ebauches. He became director of

the Le Locle Technicum, which in 1943 awarded him the degree of Doctor

Honoris Causa.

Abraham Louis Perrelet 1729-1826

Jean Moise Pouzait 1743-1793

Daniël Quare 1649-1724

Raingo (Freres)

Raingo was of French

extraction and fled (probably for political reasons) to Gand, Belgium circa 1800 and almost certainly remained there for the rest of his life. He is also recorded as being clockmaker to the

Duc de Chatres in 1823. The company became Raingo Freres circa 1825 and operated from various Paris addresses. Precious little information has come to light on the clockmaker himself (his Christian name is reputed to be Zachariah) but judging by the number of examples with retailers' names on the dials and his unfashionable location he relied heavily on others for retail.

Most of Raingo's 20-30 surviving orreries just have the basic tellurium on a circular base, the two best known examples of this type are in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle and at the Soane Museum, London. The present example with its musical movement and plinth base represents the rarest of all the types known to exist.

"Living On Air"

The History of the Legendary Atmos Clock:

In the late 1920s Jean-Leon Reutter, a young Paris engineer, experimented

with a clock that needed no direct mechanical or electrical intervention

to keep it wound, in short a clock powered only by Perpetual Motion.

For centuries, many scientist including Leonardo Da Vinci had experimented

with the idea of Perpetual Motion - however, only J.L. Reutter eventually

succeeded at incorporating that novel idea into an actual working clock.

Through out his life, J.L. Reutter's dream of a Perpetual Motion timepiece

led him to produce a clock with a timekeeping mechanism designed

specifically to consume the smallest possible amount of power to keep the

clock running satisfactorily.

After studying the design of the 400-Day Anniversary Clock -which was very

popular during that era - Reutter made significant changes to that

concept, to meet the small input power requirement he was looking for in

his new clock design.

Reutters modifications of the 400-Day Clock included changes to the

escapement leverage to reduce the arc of the escapement as well as adding

jewels to the bearings of the movement. His new clock ran safely and most

importantly very reliably.

His new clock design included a special device that would power his clock

independently, using a substance that would react to the most sensitive

changes in temperature and atmospheric conditions. That substance was

mercury. He also designed a special glass tube similar to that of a

thermometer for the mercury and encased it all inside a metal cylinder,

which is now known as the Bellows.

The result of Reutters achievement was an ingenious new clock unlike any

other, past or present. A timepiece that could run independently and

continuously and so incredibly sensitive, that it could be rewound by the

slightest fluctuations in the atmosphere, or by the slightest changes in

temperature, hence the name: "Atmos Clock".

Later, due to dangers in handling and instability, the mercury in the

Bellows that powered the Atmos Clock was changed to a special more stable

saturated gas, known scientifically as 'Ethyl Chloride'. The technological

concept of the Gas filled Atmos Bellows is a remarkable one: Inside a

sealed capsule, a mixture of gas and liquid expands as the temperature

rises and contracts as it falls, moving the capsule back and forth like a

tiny unseen accordion. This motion is used to constantly wind the

mainspring thus enabling the clock to run and keep perfect time. A small

temperature variation of just one degree is sufficient for over two day's

operation. Such variation occurs naturally in normal room temperature and

thus without any additional sources of energy, the Atmos clock will

continue to run if left untouched, "forever". Hence the term: "Living On

Air".

The Marriage of Atmos and Jaeger-LeCoultre

When Reutters Atmos was in its initial production in the early thirties,

the lack of enthusiasm from manufactures in general during that time made

production of the Atmos clock difficult. Reutter Atmos was in production,

but only in small numbers.

Legend has it, while Reutter struggled with production of his Atmos Clock,

the manager of a famous Swiss watch making company LeCoultre (a company

world famous for fine Swiss watches located in the French Valley of

Switzerland) was strolling down a street in Paris one day and noticed one

of Reutters Atmos Clocks sitting in a shop window for sale. The man was so

fascinated with Reutters Atmos; he walked in and purchased it from the

shop merchant.

Later, after a chance encounter between LeCoultre and Reutter he (Reutter)

agreed to sell the license and eventually his Atmos Clock patent to the

LeCoultre Watch Company.

At the time of LeCoultres acquisition of the Atmos patent, LeCoultre was

in fierce competition with another Watch Company, Ed Jaeger of Paris.

Eventually LeCoultre merged with Jaeger to form the famous watch making

company: Jaeger-LeCoultre.

With the combined knowledge and expertise of their newly joined Company,

Jaeger & LeCoultre poured considerable investment collective research and

development into Reutter's Atmos Clock. Just a few years later, major

production of the newly revamped Atmos Clock was launched under the

Jaeger-LeCoultre name exclusively.

The LeCoultre Atmos Clock soon became a very fashionable, prestigious gift

in Switzerland and eventually Worldwide.

As the success of both Jaeger-LeCoultre and the Atmos clock continued to

grow, the company prospered and in 1979, the 500,000th Atmos Clock left

the Factory in Switzerland with much celebrated fan-fair, a half a century

after the first Atmos Clock patent was filed.

Decimal or Revolutionary time was adopted by decree of the National Convention on November 24, 1793. It stipulated that the Gregorian calendar should be abandoned and replaced by the

Republican calendar

which divided the day into ten hours each with one hundred minutes and then further sub-divided into one hundred seconds.

Although perhaps a logical 'simplification' of timekeeping the habits of the populous were difficult to change. The new system meant having to design a new dial and to this end a competition was organised to invent one that was clear and easy to read.

Despite the efforts of some of the great horological minds the system was never really adopted and clockmakers had no real reason to fully support it because their Revolutionary clocks were useless outside

France which ruined their export trade.

By 1795 it was no longer compulsory to use Decimal time and even before then clocks and watches were being made with both the 'old' and 'new' systems.

Finally it was decreed that the Decimal system had proved impossible to implement properly and from January 1, 1805 French timekeeping reverted back to the

traditional system.

More

1)

Robin was employed as royal clockmaker to Louis XVI who installed him in the Galeries du Louvre Robin belonged to a small group of horologists who made significant advances in the quest for accurate time measurement. He also possessed a keen artistic eye and only used the finest, most modern cases and dials supplied by leading artists of his day.

Robin was appointedas Valet de Chambre-Horloger Ordinaire du Roi in 1783 then in 1786 installed in lodgings in the Galeries du Louvre on reversion of Maurice-Quentin Le Tour’s lodgings, December 1785. The King’s wife, Marie-Antoinette was equally enchanted by Robin’s work, though she tended to prefer decorative pieces of a more feminine quality. In 1786 she appointed him as her Valet de Chambre-Horloger Ordinaire du Reine. At least 23 clocks by Robin were listed in the 1793 inventory of her belongings. Robin was also much favoured by Monsieur, Louis XVI’s brother, who owned at least ten of his works. Other members of court and influential patrons included the maréchaux ducs de Duras and de Richelieu who acted as ‘Premiers Gentilshommes de la Chambre’, the marquis de Sérent, tutor to the ducs d’Angoulême and de Berry and François César marquis de Courtanvaux. The latter, who belonged to the highest-ranking nobility in the kingdom, would have truly appreciated such a work. Courtanvaux, was a member of the Académie de Sciences, was passionately interested in the sciences and had a large collection of clocks that included one of Robin’s first mantle precision regulators.

Robin was an ambitious man of great influence who achieved almost unrivalled success with a string of titles and important official posts to his name. Appointed firstly to Louis XV and then Louis XVI and his wife, his talents and the patronage of the royal family enabled him to count among his clientele the cream of the Parisian high society. Yet despite his prestigious position within the horological world little is known of his youth and early training. He was born in Chauny, north east of Paris in 1741 and then at the age of 23 was appointed to King Louis XV as Marchand-Horloger Privilégié du Roi. Robin resigned two years later and in 1767 was received as a maître-horloger. The most brilliant phase of his career began in 1778 when he was appointed Horloger du duc de Chartres and the Académie des Sciences approved two of his inventions. One was an astronomical clock representing a meridian drawn on a pyramid, which the Menus-Plaisirs acquired the same year for King Louis XVI. In 1778 he also published a highly acclaimed article, which he presented to the Académie entitled “Mémoire contenant des réflexions sur les propriété du Remontoire, un éschappment naturel avec une courte description d’une Pendule dans lacquells ces effets sont execute”.

Famed for his mantle clocks, which featured astronomical indications and compensated pendulums, of which the marquis de Courtanvaux owned one of the first, Robin also applied the same principal to regulators, among which was an early example acquired by the duc d’Aumont. Equally interested in watch making, from 1786 he used a special type of escapement, which he also incorporated into his monumental clocks, supplying for example those at the Grand Commun at Versailles in 1782 and at the Petit Trianon in 1785.

Robin spent his entire career in Paris. By 1772 he was established at Grande rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, by 1775 at rue des Fossés-Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois and by 1778 at rue Saint-Honoré at the Hôtel de l’Aligre. Then in 1786 he moved to the Galeries du Louvre, where he was at the king’s command and where he constructed this outstanding regulator.

Though Robin thoroughly enjoyed the patronage of royalty and aristocracy, he showed little sympathy toward them during the Revolution. Whether he feared or actively believed in the new political regime he soon found favour with the new Republican government. Thus from former royal clockmaker he was appointed Horloger de la République, 1794 and then Horloger du Directoire, 1796. Robin’s work from this period include a decimal clock made as a gift to the National Convention, 1793 and a ‘Louis XIV clock’, which he converted into a ‘Clock of Liberty’, 1798. Robin died in Paris on 17th July 1799; undoubtedly had he lived longer he would have excelled under the Emperor Napoleon. Robin’s sons, both brilliant clockmakers continued his dynasty and under the Restoration held the titles of Horloger du Roi and Horloger de Madame la duchesse d’Angoulême, daughter of Louis XVI.

As one of history’s truly great clockmakers, works by Robin continue to be prized among the world’s finest private and public collections. The impressive list includes the Château de Versailles, the Musées du Louvre, Arts Décoratifs, National des Techniques, Conservatoire des Arts et Metiers and National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris and the Musée Paul Dupuy, Toulouse. Robin’s work is also conserved at the Wallace Collection, the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Guildhall, London as well Baron Rothschild’s former residence at Waddesdon Manor, Buckinghamshire. The Musée d’Horlogerie; La Chaux-de-Fonds; the Deutsches Museum, Munich and the Museum der Angewandten Kunst, Vienna all own examples of his work as do the Patrimonio Nacional, Spain; Pavlovsk and the Hermitage, at Saint Petersburg. American collections include the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Huntington Collection, San Marino and the Institute of Art Indianapolis.

Portrait of Robin.

Jean Romilly 1714-1794

Romilly,

Jean, Paris. Born in Geneva 1714 of a refugee father, d. 1794. Married in Paris in 1752. He is listed at the Quai

Pelletier, 1752, Place Dauphine, 1772-1781 and Rue Poupee 1787-1789. Tardy records a Louis XV cartel clock signed Romilly a Paris. In 1755 he is recorded as making watches beating seconds and 1768 a marine timekeeper damaged during trials. He wrote the technical part on horlogerie in the Encyclopedic

Methodique.

Object

by Romilly.

Georg

Frederic Roskopf 1813-1889

La Chaux de Fonds.

Georges F. Roskopf (1813-1889) was born in Germany and became a

naturalized Swiss.

In 1829 he went to La Chaux de Fonds and began training in commerce with

F. MAIRET & SANDOZ who dealt in ironmongery and watch parts.

In 1833 he decided to become a watchmaker and went as an apprentice to J.

BIBER in La Chaux de Fonds to learn watchmaking.

Financed by his wife, he then set up in business as an établisseur, that

is, a watch producer who bought the ebauche and all other parts of the

watch and assembled them. He made cylinder and lever watches for export to

North America and Belgium.

The watches were well made, the business was not profitable and in 1850

Roskopf sold it.

In 1851 he became joint manager of the La Chaux de Fonds branch of B. J.

Guttman Frères of Wurzburg. They made English-type watches.

In 1855 Georges Roskopf set up in business with his son, Fritz Edouard,

and Henri Gindraux as ROSKOPF, GINDRAUX & CO.

After two years his son opened his own business in Geneva and Gindraux

went to Neuchâtel to become Director of the Watchmaking School.

Roskopf was an idealist who dreamed of making a good quality, cheap watch

for working men. To accomplish this he used an old idea and reworked it,

that of having the hands driven directly by the mainspring.

In 1860 he began to design such a watch which could be sold for 20 francs,

and would still be of excellent quality, simple and solid. The watch had a

large barrel in the center. a "Perron" pin lever escapement, and a

monometallic balance. After discussions with Moritz J. Grossman he adopted

the simple detached pin lever escapement.

Listing of the features for the new caliber:

1 Escapement on a platform normally using a pin lever design but possible

with a lever or cyinder escapement;

2. No center wheel but a large barrel;

3. Motion work to hands direct from the barrel arbor;

4. Philippe free spring with no stopwork;

5. Button wind but with handset by finger pressure.

Roskopf met indifference and hostility among the watchmakers of the area

who were still working as a home industry and who did not wish to make a